G.I. Joe was the codename for America’s daring, highly trained special missions force. Its purpose was to defend human freedom against Cobra, a ruthless terrorist organization determined to rule the world. From 1982 until 1994, Hasbro’s G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero was one of the driving forces in kid’s entertainment, conquering the worlds of comic books, animated television, and tiny toy action figures. With so many facets to the fandom, we thought it was time to fill you in on the history of this influential media monster.

THE ORIGINS OF A HERO

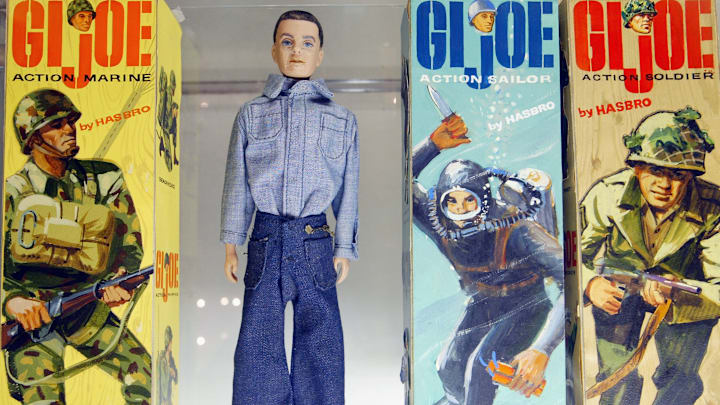

G.I. Joe began life as a nearly 12-inch military toy in 1964, creating a whole new category of “action figures” for boys that rivaled Mattel’s Barbie doll in popularity. Sales began to slip over time, so, in 1970, Hasbro changed Joe from a soldier to an “action hero,” trading his tanks and jeeps for inflatable rafts and a patented “kung fu grip.” By the time the line was cancelled in 1976, Joe had become something of a superhero, incorporating fantastic elements like the chrome-plated Bulletman and the bionic limbs of Atomic Man, who battled The Intruders, a group of cavemen from outer space.

An Uphill Battle

By 1979, Hasbro’s Head of Boy’s Toys, Bob Prupis, was ready to bring Joe back. Prupis’ secret plan for the G.I. Joe reboot, code named “Operation: Blast Off” on internal memos, was a Mission: Impossible-style toy line that had one foot in the future, with the other grounded in contemporary military technology. It would feature science fiction-inspired weapons like laser artillery and jet packs, next to realistic depictions of tanks, rocket launchers, and submachine guns. However, his idea was met with resistance from Hasbro executives.

One of the first hurdles Prupis had to clear was the price of petroleum. Middle East oil suppliers had cut production, causing the cost of petroleum to jump from $15 to nearly $40 per barrel. The increased expense of this raw material for plastic would have to be passed on to the consumer, meaning the retail price of new 12-inch G.I. Joe figures and vehicles would be too high for the average household.

So Prupis took inspiration from the “little green army men” he used to play with as a child, as well as from the popular Star Wars line of action figures produced by rival toy company, Kenner, and sized Joe down to 3 3/4-inches high to save on plastic. But even the smaller Joe concept was turned down by management, simply because it “wasn’t exciting enough.” For the next two years, Prupis kept going back to the drawing board to try to find some new hook that would make Hasbro bite, but he was rebuffed every time.

Two-Week Notice

Then, in 1981, after yet another failed attempt to get Blast Off off the ground, Prupis was told that he had one more shot with Joe, or else he needed to move on to other ideas. Prupis would be given two weeks with Griffin-Bacal, the marketing firm that managed Hasbro’s advertising, to see if he could come up with something to get kids excited about G.I. Joe again. Prupis pulled together a team, including Kirk Bozigian from marketing and toy designers Ron Rudat and Greg Bernstein, to brainstorm product and promotional ideas.

Although they came up with a lot of fun concepts, they faced a big marketing stumbling block—there was no G.I. Joe movie to tie into like Kenner had with Star Wars. Instead, it was suggested that a comic book might work just as well.

Marvel-ous Assist

Just how Marvel Comics and Hasbro came together is a mix of legend, reality, and fuzzy memories from nearly 40 years ago. One version of the story states that the CEO of Hasbro and the president of Marvel met in the men’s room at a charity function, where the two got to talking shop. However, Hasbro’s Bozigian says that it was Griffin-Bacal that contacted Marvel to discuss working on G.I. Joe. Whatever the case, Marvel was willing to help, and the relationship between the two companies was born.

Marvel took a special interest in G.I. Joe, because Griffin-Bacal wanted to try something new for the comic book—television advertising. There were government regulations required for toy commercials, including: restrictions on runtime; the ad had to show kids playing with the actual toys; and animation was limited to only a few seconds. However, there were no such rules regarding advertising for comic books, because it had simply never been done before. Griffin-Bacal took the risky move of dedicating $3 million to create a series of 30-second animated commercials for the Marvel G.I. Joe comic book. Naturally, the comic featured all the action figures and vehicles from the toyline.

Fury Force

After seeing the G.I. Joe concept, Marvel Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter realized it was similar to something that writer/artist Larry Hama had been developing, called Fury Force. Fury Force was a series starring the son of Marvel’s spy extraordinaire Nick Fury as the leader of a seven-member paramilitary strike team. Hama had drawn character designs and basic biographies, but the series hadn’t been picked up by Marvel, so he set it aside. But instead of letting Hama’s hard work collect dust, Shooter suggested adapting his ideas to fit G.I. Joe instead. And just like that, Hama was in charge of the comic book series that would one day define his career.

Enter Cobra

Because enemy toys had never sold well in the past, Hasbro hadn’t even considered a foil for G.I. Joe. But Hama insisted that “these guys can’t just march around and go on maneuvers or whatnot, they have to be battling some things, some threat...” It was Marvel writer Archie Goodwin that suggested a terrorist organization named Cobra. Inspired by the name, Ron Rudat developed the design for the enemy’s now-iconic logo.

Birth of the File Cards

Hama kept a series of handwritten index cards to keep all of the characters and vehicles for the comic book straight. On each card he would write a few details, including biographical notes and military specialties. Hasbro had already considered including trading cards with the toys, but they liked Hama’s index cards so much they asked him to write more so they could be included on the back of the figure packaging for kids to cut out and collect. These “file cards” became a key aspect of the Joe toyline and nearly all of them were written by Hama.

Blast Off Blasts Off

With exciting new figure and vehicles designs, interesting characters, and innovative advertising ideas, Bob Prupis approached Hasbro executives once again to reboot G.I. Joe. It’s been said that CEO Stephen Hassenfeld was so excited by the presentation, that when it was over he had tears in his eyes.

The initial line of 3 3/4-inch G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero action figures debuted in the summer of 1982. Nine Joes—Breaker, Flash, Grunt, Rock ‘n Roll, Scarlett, Short-Fuze, Snake Eyes, Stalker, and Zap—were released on carded packaging similar to those used by Kenner for Star Wars figures. An additional four Joes—Clutch, Grand Slam, Hawk, and Steeler—were included with some of the seven vehicles that made up the original toy line. Two Cobra figures—a Cobra soldier and a Cobra officer—were also released on carded packages.

The first year sales projections for the new line of G.I. Joe toys was $12 to $15 million. The line wound up selling over $50 million worth of product, and was the hot new toy to have that Christmas.

Evolution of the Toys

After its phenomenal first year, Bozigian says the G.I. Joe line was given carte blanche to do whatever they wanted with the second series of toys. Vehicle designer Greg Bernstein ramped up the detail and the ambition on the second line of vehicles. Similarly, Ron Rudat, who designed every action figure from 1982 to 1985—somewhere in the neighborhood of 125 figures—added more detail and color to the handful of character sketches he turned in every day. But the biggest change for the line was in poseability.

From the beginning, G.I. Joe figures featured more articulation than the competing Star Wars figures. Whereas Star Wars figures had five points of movement (arms, legs, and head), G.I. Joes had 10 points: arms, legs, elbows, knees, torso, and head. However, in order to make the second wave of Joes even better, two swivel joints were added at the character’s bicep, allowing the arms to turn in towards the body to let the figures hold their rifles more realistically. This “Swivel-Arm Battle Grip” was clearly the future of the franchise, so the original figures were re-released, creating a definitive line between the original figures—now known as “straight-arm figures”—and the rest of the toys going forward.

Flag Points

Because Cobra was more of an afterthought for Hasbro, they didn’t have the design for the Cobra Leader, better known as Cobra Commander, done in time for the line’s launch. So instead, they implemented another idea from that early brainstorming meeting: mail-away exclusives. Kids needed to collect proofs of purchase, known as “Flag Points,” found on every package, and send them, along with a check for 50 cents to cover shipping, to get their free Cobra Commander figure. On the What’s On Joe Mind podcast, Bozigian said that Hasbro expected about 5000 orders for the new figure, but between January 2 and March 31, 1982, they received over 125,000 order forms. The popularity of the mail-in offer spawned a new program for the company called Hasbro Direct, which gave kids the opportunity to buy overstocked, hard-to-find, and exclusive figures and vehicles.

Foreign Duty

G.I. Joe might have been a real American hero, but he was popular all over the world, with figures and vehicles available in countries as diverse as Japan, India, Brazil, Canada, Italy, China, and many more.

There wasn't a lot of continuity between the American and foreign lines, as many toys had different codenames, file cards, paint schemes, and could even be on a different side in the battle between G.I. Joe and Cobra. For example, in Britain, where the figures were called Action Force: International Heroes, Cobra’s black H.I.S.S. Tank, was the crimson red “Hyena,” and was driven by a repainted Destro known as “Red Jackal.” In Spain, the laser infantryman, Sci-Fi, was known as “Sargento Láser,” and Quick Kick was called “Kung-Fu.” Spain also had the most unique file cards, with translation errors that left the cards riddled with nonsensical phrases. It’s an inside joke with the Joe collector community that the file cards were written correctly, but then a mischievous cleaning lady at the Hasbro Iberia office would edit them overnight, so they would be a mess before they were sent to the printer the next morning.

Some of the most sought-after foreign Joes were those manufactured in Argentina by toy company Plastirama. The figures were made from inexpensive plastic, with even flimsier cardboard packaging, to the point that very few examples still exist today. The initial seven figures, now known as the “Argen 7,” are virtually impossible to come by. Needless to say, they fetch a high price on the collector's market. This Cobra Mortal figure, a heavily repainted Snake Eyes, recently sold on eBay for $599. The packaging is even more rare, with a recent auction on eBay asking $5200 for the complete set of Argen 7 file cards.

A Slow Defeat

The G.I. Joe toyline's popularity peaked in 1986, before sales started to slide a year later. But it wasn't all the Joes' fault. There were new heroes in a half-shell in town that were radically changing the landscape of action figures.

The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles toys from Playmates were brightly colored and featured off-the-wall designs that kids loved. In an effort to keep up with the trends, Hasbro made the Joes more colorful, added more outlandish details, and included large, spring-loaded weapons.

Much like the 12-inch Joes of the 1970s, by the end of the Real American Hero line in 1994, G.I. Joe had moved away from its military roots. Now, the Joes and Cobra were broken into sub-groups like Star Brigade, who battled alien creatures called The Lunartix Empire; the neon costumed Ninja Force; a drug enforcement team; a group that fought against eco-terrorism; and some dinosaur hunters. Hasbro also tried tying the Joes in with the popular video game Street Fighter 2 by integrating characters like Chun Li, Blanka, and E. Honda into the mix. It felt like Hasbro was grasping at straws, so when they announced the cancellation of the toyline in 1994, fans were disappointed, but not necessarily surprised.

Collector's Holy Grails

The G.I. Joe collector's market is easily one of the most active communities for 1980s toys, with fans combing through eBay and online forums looking for those last few Holy Grails to complete their collection. Of course, professionally graded, popular figures that are still in their original packaging demand top dollar. For example, a Snake Eyes figure that met these requirements recently appeared on eBay for $1350, and a Storm Shadow appeared for $1200. But there are a few underrated figures that only a serious collector would know to look for.

One example is Heavy Metal, released with the Mauler tank in 1985. Oddly enough, it's not the tank that's unusual, but Heavy Metal's microphone headset. The headset was a small, light brown piece of flexible plastic that attached to the side of his helmet, and was easily lost by kids. A Heavy Metal figure on its own, usually with a reproduction dark brown or black microphone, will sell for about $40. With the original microphone, a collector should expect to pay over $150.

In 1988, Target featured an exclusive version of the Joe character Hit & Run that came with a parachute pack. The parachute had been sold by Hasbro Direct before, but the instructions for using the parachute that were packaged with the Target figure were much smaller, and therefore easier for a kid to lose. About the only way to get a complete Hit & Run Airborne Assault Parachute Pack is to buy one in the original packaging, which will set you back around $500.

Starduster was a mail-away figure that was initially only available by sending in a coupon from a box of G.I. Joe Action Stars cereal. The figure was cobbled together from different parts of different Joes over his lifespan, but an original “Version A” Starduster, using Flash’s head, Flint’s arms, Roadblock’s legs, and Recondo’s torso and hips, is a rarity, recently selling on eBay for $245. Another auction with this Version A Starduster still in the bag he was shipped in, sold for $560.

Starting in 1987, Hasbro offered kids the chance to get their own customized Joe figure, called Steel Brigade, from Hasbro Direct. Kids would fill out a form with check boxes, noting what kinds of special skills and weapons proficiencies they wanted the figure to have, as well as a codename and place of birth, and send it in with a few Flag Points. The helmeted figure would arrive in the mail a few weeks later, along with a printed file card with the stats chosen by the recipient. There were a few different versions of the Steel Brigade figure available, but the one with a shiny, gold helmet was the rarest of the bunch. A “Gold-Headed Steel Brigade” still in the original sealed plastic bag, recently sold on eBay for $666. An unbagged Gold Head will sell for $320 or more. Even a non-Gold Head with all of his accessories can fetch $100 if it's in good condition.

There are, of course, vehicle and playset Holy Grails, too, including the Cobra Terror Drome, a circular command post for Cobra that included a small Firebat jet that docked in the center. This fairly large playset contained many pieces that could be lost or broken, so to find one today, complete with the box, expect to pay a little over $550.

The earliest Grail is the Cobra Missile Command Headquarters, an inexpensive playset released in 1982 exclusively at Sears. The set includes pieces of printed, perforated cardboard that could be punched out, folded, and put together to form a missile base for the included Cobra Infantry, Cobra Officer, and Cobra Commander figures. Because the set was only sold at Sears, and was made of cardboard, it's a rare find on the collector's market today, fetching $200 to $300 for one in good condition, and $1000 or more with the box. A recent eBay auction saw a brand new, never assembled playset, go for $2000.

In 1987, Hasbro released the Defiant, featuring a rolling launch platform for a Space Shuttle inspired orbital space station with a separate vehicle attached to the back. The playset was massive, including dozens of easily lost or broken parts, which makes it hard to find in good condition. So a collector paying nearly $1000 for a complete set is not unusual. If they demand the box be included, they can look to spend around $2200. Even the two figures that came with the set—Payload and Hard Top—regularly sell for over $100 each.

Finally, we have the USS Flagg aircraft carrier. Based on research gathered by Hasbro designers during a special visit to the Quonset Naval Base in Rhode Island, the Flagg is over 7.5 feet long, outfitted with a microphone for calling out orders, lifts to bring aircraft up to the flight deck, and more parts than any 8-year old could ever keep track of, it is often found on lists of the greatest toys ever made. Originally retailing for $109, a complete Flagg without the box sells for about $1300; with the box, expect to pay upwards of $2200.

The Comic Book

The Marvel comic book debuted in June 1982, accompanied by the animated television advertising campaign, the book was a smashing success at launch. Kids who didn’t usually buy comics swarmed to the title, selling out the first few issues, and requiring additional print runs to meet demand. After this initial burst of activity, the comic settled into fairly low sales, averaging just under 160,000 issues per month by 1983.

But thanks to Hama—who had had served in the military during Vietnam, and so was able to provide a realistic foundation for the comic book storyline—the book continued to build an audience. According to Jim Shooter, by 1985, the comic was leading Marvel’s subscriptions, beating out familiar titles like The Amazing Spider-Man and X-Men. Then, with an additional boost from the cartoon series debut, Comichron.com shows that in 1986, the comic fared much better, averaging nearly 331,500 issues sold every month.

The Marvel G.I. Joe comic book lasted for 155 regular issues, as well as four yearbooks that recapped the year’s events in the regular series. The comic was also spun-off into G.I. Joe: Special Missions, a 28-issue series that featured stand-alone stories told outside the regular series’ canon, as well as 18 issues of G.I. Joe: European Missions, which were reprints of the British Action Force comics. There were a few limited series as well, including the four-issue Order of Battle, a comic book version of the file cards found on the back of the action figure packaging, as well as a crossover with Hasbro’s other big property in G.I. Joe and the Transformers. To help new readers catch up, many of the early issues were republished as Tales of G.I. Joe and in G.I. Joe Comics Magazine. Finally, in 1995, G.I. Joe Special was a one-shot reprint of issue #61, featuring the original artwork by Todd McFarlane. The art had been deemed unacceptable when he first drew it, but after McFarlane helped to revitalize Spider-Man and founded Image Comics, it was suddenly deemed acceptable for publication.

Elevating the Art Form

Fans would fondly remember the G.I. Joe comic, but one particular issue—G.I. Joe #21, published in March 1984—has become something of a legend in the modern era of comic books.

The story, titled “Silent Interlude,” featured the G.I. Joe commando, Snake Eyes, infiltrating a mountaintop castle to rescue fellow Joe, Scarlett. The mysterious, masked Snake Eyes was wounded in Vietnam, leaving him mute, so Hama thought it would be interesting to have a story where the silent character could have a silent adventure. The entire story was told purely through visuals with no dialog or even sound effects, yet it was a perfectly encapsulated tale with action, intrigue, emotion, and an amazing stinger at the end that hinted at a connection between Snake Eyes and a new foe, the Cobra ninja, Storm Shadow.

Hama had always wanted to do a completely silent story, and his chance came when the book’s production was running behind schedule. By writing a silent story, and handling the cover and interior artwork himself (with inks by Steve Leialoha), Hama cut at least a week off production and was able to get the book out on time.

The issue wound up becoming what Scott McCloud, author of Understanding Comics, called “a kind of watershed moment for cartoonists of [our] generation. Everyone remembers it.” The comic was recently reprinted in a new hardcover edition, featuring an interview with Hama, as well as his original pencil breakdowns, and more information about the creation of this iconic issue.

The Final Mission

Larry Hama wrote the entire comic book series without a net—there were no outlines, and no master plan. He scripted nearly every issue on the fly, saying that if he didn’t know what was going to happen next, then neither would the reader. But it was this off-the-cuff style that helped keep the book’s vitality through an unusually long run for a toy tie-in comic. The final issue of the comic, #155, featured the deactivation of G.I. Joe and the shuttering of their headquarters.

The Cartoon

When Hasbro relaunched the G.I. Joe franchise in 1982, cartoons were heavily regulated by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to ensure that companies were not marketing products to kids. It was fine for cartoons to be based on comic book and comic strip characters, like Smurfs and Superfriends, whose likenesses were plastered all over merchandise from different companies. But if a single company tried to make a cartoon that was based on a toyline they alone produced, it was seen as little more than a half-hour commercial for their products, which was not allowed by the FCC.

However, one of the major goals of President Ronald Reagan’s administration was to deregulate American industries. So under pressure from toy companies as well as TV networks, who wanted the extra money half hour ads would bring in, the FCC decided in 1984 that program-length commercials were an innovative means of financing shows and, therefore, acceptable. This opened the floodgates for toy companies to produce their own half-hour cartoons based on toylines, and within a year, the 10 best-selling toys in America all had accompanying kid’s television shows. And one of the leaders in this brand new industry was Hasbro with G.I. Joe.

The G.I. Joe cartoon was co-produced by Sunbow Productions, a subsidiary of Griffin-Bacal advertising, and Marvel Productions, of Marvel Comics. The show was syndicated, so it could run at any time of day; however, most channels ran it during an after-school block that typically spanned from 2:30 p.m. to 5 p.m.

To kick off the series, Sunbow/Marvel produced the first ever animated miniseries for kids, titled simply G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero, though most fans know it as G.I. Joe: The M.A.S.S. Device. Airing from September 12 to 16, 1983, on 122 stations across the country, the five-part series proved to be a winner, beating out the Saturday morning cartoon ratings of all three major networks. This was followed by another five-part miniseries, G.I. Joe: The Revenge of Cobra, airing September 10 to 14, 1984, leading into the regular series, which began on September 16, 1985.

The show ran for two seasons, ending in 1986, with a total of 95 episodes, and is considered by many kids of the '80s to be their definitive G.I. Joe experience.

Ho, Joe!?

According to Wally Burr, the voice director for the show, the Joes’ famous battle cry, “Yo, Joe!” was originally written as “Ho, Joe!” by Ron Friedman, screenwriter for the two miniseries and the first story arc of the regular series. But when the actors said it, it just didn’t have the weight that Burr was looking for, so he asked that they add a “y” sound in the middle to make it “Hyo, Joe!” instead. Once the writers caught on, they changed it to simply “Yo, Joe” in future scripts. Though the battle cry was never used in the Marvel comic book, as the catch phrase permeated the fandom, Hama did give a nod to it by naming the Joe’s favorite soft drink, YoJoe Cola.

Knowing is Half the Pork Chop Sandwiches

In order to show that the cartoon was not just a half-hour commercial for the toys, but was actually educational, Sunbow added a small public service announcement at the end of every episode to teach kids some sort of lesson. Overseen by Dr. Robert Selman, a professor at Harvard’s School of Education and Human Development, each PSA typically featured a member of the Joe team meeting a couple of kids and lending a helping hand or words of encouragement. Once the kids saw the light of day, they would always finish by saying, “Now I know!” and the Joe would reply with the now-infamous phrase, “And knowing is half the battle...”

As if that famous phrase didn’t have enough of a cultural impact on an entire generation, the G.I. Joe PSAs also have the distinction of becoming the subject of some early viral videos. In 2003, Eric Fensler used the video from the Joe PSAs, but replaced the audio with bizarre, sometimes offensive phrases that were at times disturbing and nonsensical, but always oddly hilarious. They were soon being passed around via email and are now scattered all over YouTube.

G.I. Joe: The Movie

The cartoon series culminated with 1987’s G.I. Joe: The Movie. Originally meant to be a theatrical film, Hasbro’s 1986 theatrical releases My Little Pony: The Movie and Transformers: The Movie, both performed poorly at the box office, so the company decided to just release the movie direct-to-video, and then later as a five-part miniseries in syndication. The film introduced a new Joe—Falcon, voiced by Don Johnson at the height of his Miami Vice fame—as well as Golobulus, a new villain who was voiced by Burgess Meredith, perhaps best remembered as the Batman TV series’ Penguin.

Duke's Dead, Baby; Duke's Dead.

After five years—much longer than the toyline was expected to survive—Hasbro was looking to replace some of the main characters to keep the line fresh. Duke was on the chopping block, so the cartoon's story editor, Buzz Dixon, suggested they send him out with a hero's death. In the film, Duke gets hit by a snake spear thrown by Serpentor, and purely going by the visuals in the scene, he clearly dies. But a dubbed-in line reports that he has only fallen into a coma. Finally, just moments before the film ends, we hear that Duke is miraculously going to make a full recovery.

When the decision was made to kill off Duke, Hasbro suggested that the people writing the Transformers movie also have a dramatic death to up the ante from the afternoon cartoon. However, when the Transformers movie was released and thousands of little kids saw Autobot leader Optimus Prime die at the hands of the Decepticons' Megatron, Hasbro received a lot of angry letters from parents saying their children had been traumatized by the death of their hero. To spare themselves more backlash, Duke was granted a stay of execution.

Cobra-Lame

For many fans, the film marks the point where G.I. Joe “jumped the shark,” moving from a fairly realistic military toyline to a more science-fiction/fantasy aesthetic with the introduction of the Cobra-la storyline.

According to Product Manager Kirk Bozigian, as Hasbro was gearing up to produce the G.I. Joe movie, Joe Bacall, of Griffin-Bacall and Sunbow, expressed concerns about producing a 90-minute war movie aimed at kids. Bacall, a big science-fiction fan, suggested using a more fantastic enemy than Cobra in an effort to soften the Joe's edge. Hasbro was growing tired of Cobra Commander anyway and wanted to replace him with a new, more dynamic leader, the Cobra Emperor, Serpentor.

Coincidentally, Buzz Dixon, had told Hasbro that he wanted to work up a miniseries that would tell the origin of Cobra and the rise of Cobra Commander. So Hasbro told him to go for it and to work in the new Cobra Emperor while he was at it.

One of the ideas Dixon developed was that Serpentor would be the Frankenstein-ian creation of Dr. Mindbender and Destro, using the combined DNA from some of the greatest military leaders in history. His other story idea would take the origin of Cobra back to an ancient race that lived in a land called Cobra-la, a play on the fabled city of Shangri-la. However, Cobra-la was always meant to be a placeholder name until they could come up with something better. When he pitched his ideas to Hasbro, instead of choosing one, they chose both and insisted he keep the name Cobra-la. Dixon wasn’t thrilled with the idea of combining the two concepts, but he had to make it work. Bozigian has also made no bones about the fact that the Joe team at Hasbro was not a fan of the Cobra-la angle, but they also had to make it work.

Larry Hama, on the other hand, stood his ground. In issue #100 of the comic, Hama responded to a fan letter by saying he had already been stuck with “a host of silly characters,” like Serpentor, and the twins, Tomax and Xamot, so he “drew the line at Cobra-la.” The closest Hama ever came to Cobra-la was writing a one-shot comic released with a twin-pack of figures featuring a battle between Nemesis Immortal, Cobra-la's heavy, and the Joes' Lt. Falcon. If there was any doubt as to how Hama felt about Cobra-la, Falcon beats up on Nemesis, who barely lays a finger on the hero, before the rest of the Joes take out the enemy with couple of missiles.

Series 2 Cartoon

Hasbro had been funding the G.I. Joe cartoon out of their own pockets since the beginning. So when production company DIC offered to shoulder most of the expense of a new cartoon series, Hasbro jumped at the chance. The show’s production values were much lower than the Sunbow cartoon, with less-detailed animation, a smaller cast, and even goofier storylines that were clearly aimed at a younger audience. The show ran from 1989 to 1992 for a total of 44 episodes and is generally not popular with Joe fans.

Still Fighting Strong

A toyline is considered a success if it stays on the market for two or three years. The Real American Hero toyline ended in 1994, after 12 years on the market. Other Joe-related toylines, like Sgt. Savage and the Screaming Eagles (1995), G.I. Joe Extreme (1995), Sigma 6 (2005-2007), and tie-in toys for the two live action films, 2009’s G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra and 2013’s G.I. Joe: Retaliation, have been released, but none have found the measure of success that was seen in the 1980s. There are still new 3.75-inch G.I. Joe figures released nearly every year, but they're exclusively available at G.I. Joe conventions or through the G.I. Joe Collector's Club.

Although Marvel stopped publishing the G.I. Joe comic when the toyline was canceled in 1994, other companies, like Dark Horse, Fun Publications, Dreamwave, Image/Devil’s Due, and most recently, IDW, stepped in to present their own version of the Joes. While most follow-up series have used many of the same characters, they have not been in the same continuity as the original run at Marvel—until IDW brought Larry Hama on board in 2010 to pick up where he left off with a special Free Comic Book Day issue, #155 1/2. The ongoing IDW series is still being printed today with Hama at the wheel, and shows no signs of stopping.

So now you know the history of G.I Joe: A Real American Hero. And knowing is half the battle...

Additional Sources: The Ultimate Guide to G.I. Joe 1982 - 1994: Identification and Price Guide; Tim Finn's website.