If automotive futurists are correct, we'll soon be living in a world where self-driving vehicles from Tesla and other carmakers transport us from one destination to another while we sit idle in the cabin. While this dream scenario seems to have taken off in recent years, engineers have actually been trying to accomplish autonomous cars since the early 20th century. Take a look at some fascinating—and sometimes misguided—attempts to take us out of the driver’s seat.

1. The Radio-Controlled Car That Led to Houdini’s Arrest

Residents of New York City in the summer of 1925 were greeted with an unusual sight—a driverless vehicle ambling down Broadway. The modified Chandler sedan, dubbed the American Wonder, was the work of Francis P. Houdina, a former U.S. Army electrical engineer. The American Wonder received radio signals via an antenna that controlled its speed and direction. A second vehicle containing the car’s operators trailed just behind it. The car could even honk its horn. While this glimpse of the future was intriguing, it ended somewhat ignobly when the American Wonder careened into a car containing a bunch of photographers.

The story has a strange epilogue. Famed escape artist Harry Houdini was reportedly so annoyed that Houdina’s publicity led to the public confusing the two of them—Houdina sometimes received mail intended for Houdini—that the magician and his secretary, Oscar Teale, were arrested for breaking into Houdina’s office to retrieve correspondence meant for Houdini. The charges were later dropped.

Despite this peculiar wrinkle, various iterations of a “phantom” automobile operated by radio control appeared for years, though not with consistent success. In 1932, a phantom car operated by engineer J.J. Lynch plowed into a crowd in Hanover, Pennsylvania, striking 12 people.

2. The Nebraska Test

While radio-controlled vehicles by themselves ultimately proved insufficient, there was no shortage of other ways to get driverless vehicles moving on the road. In 1957, an experiment was conducted on U.S. 77 near the Nebraska 2 intersection near Lincoln, Nebraska, that involved a Chevrolet being guided by wire coils located underneath the pavement. State traffic engineer Leland Hancock devised the method and enlisted electronics manufacturer RCA to aid in his attempts to automate vehicles. The project was inspired in part by a 1939 World’s Fair concept of a driverless future as envisioned by industrialist Norman Bel Geddes. During the demonstration, an RCA representative used coils on the car’s bumper to communicate with the guide wire under the road. To prove the car was guided by the coils and radio transmission, the windshield was blacked out. Hancock believed this would be a viable method of driverless control, but the cost and effort in laying guide wire proved to be an insurmountable obstacle.

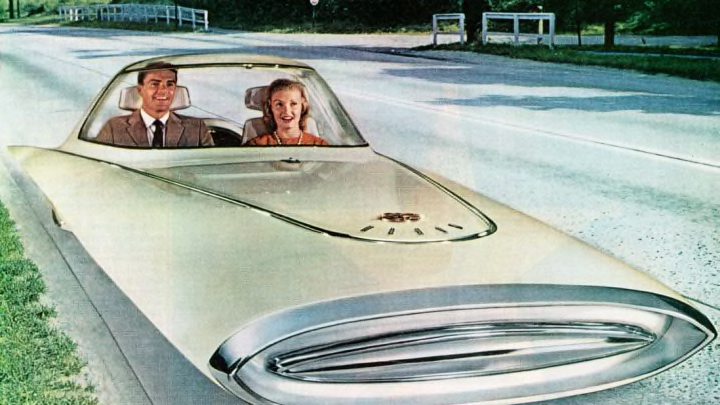

3. The Titanium Firebird

Believed to be the first car constructed entirely of titanium, the Firebird II from General Motors made a splash in 1956 when the carmaker proposed it could be controlled by an electronic strip located under the road. A retractable steering wheel would disappear, handing the car over to a kind of autopilot system that would be overseen by traffic control towers similar to the kind found in the aviation industry. GM correctly predicted voice-activated features and display screens. The speculative effort hit the road for a demonstration in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1960 and never went far beyond that, though you can watch the excellent promotional video above.

4. The Aeromobile Arrives (Sort Of)

In 1961, Popular Science profiled William Bertelsen, a physician who dabbled in engineering and developed a hovercraft vehicle. His Aeromobile would glide in “airways” rather than on highways and speed along at hundreds of miles an hour while drivers kicked back and read newspapers. Bertelsen actually built an Aeromobile, dubbed the Aeromobile 35B, that used a downward rather than inward stream of air to propel itself, which allowed for better steering. His high-speed utopia of air cars, however, never materialized. Engineers in Britain were far ahead of the United States in the hovercraft field, minimizing American interest in the vehicles.

5. The Ghost Car

In attempting to test tire reliability in 1968, German carmaker Continental struck upon a method for driverless vehicle operation. The demonstration, which took place at the Contidrom test track in the Lüneburg Heath and was developed by Siemens, Westinghouse, and researchers at the Munich and Darmstadt universities, used a guide wire on the road. When the car veered away, sensors alerted the system and steered the car back into place. A control station could instruct the vehicle to brake and accelerate.

The “e-car” was put into regular use on the track, which impressed observers by zipping around with no one behind the wheel. Sheets of glass along the track told the engineers how different tire treads responded to different conditions. The strategy was used through 1974.

6. The Ambulance of the Future

In 1989, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University motored around campus using ALVINN, or Autonomous Land Vehicle In a Neural Network. The computer-powered vehicle, a former Army ambulance, had a CPU the size of a refrigerator and used a 5000-watt generator for power. Essentially, the car could drive using the information stored on its network rather than rely on a predetermined grid in the environment. The former Army ambulance vehicle is thought to be a predecessor of the self-driving vehicle networks in use today. In 1995, the group took a 1990 Pontiac Trans Sport 3100 miles across the country, steering autonomously while a human worked the brakes and hand throttle.

7. The Car with Eyes

In 1994, German engineer Ernst Dickmanns saw his dream of a self-driving car realized when he was able to put two Mercedes 500 SEL limousines on a public road in Paris, France, that had no human operator. The cars had an onboard computer system controlling the wheels, gas, and brakes. Dickmanns’s work had stretched back to 1986, when he had outfitted a Mercedes van with a computer and cameras, allowing it to receive information like lane markings from the road. The work culminated with the test drive in actual traffic, with drivers on hand to take the wheel if needed. Though Dickmanns’s work foreshadowed much of the surveillance elements of today’s modern self-driving cars, his backers wanted more immediate results and eventually withdrew funding.