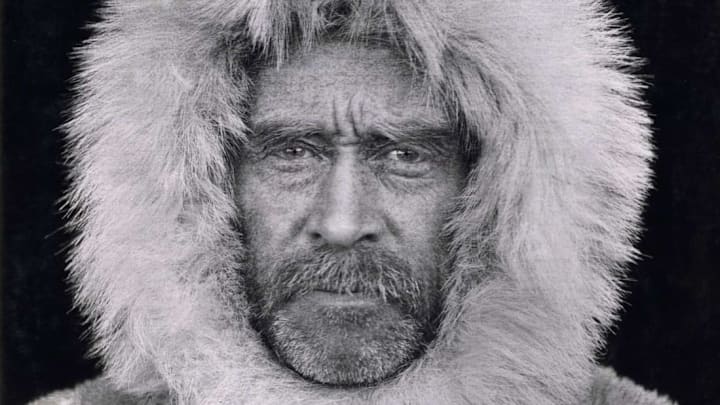

Robert Edwin Peary, called "one of the greatest of all explorers," claimed to have been the first person to reach the North Pole on April 6, 1909. But from the moment his achievement was announced to the world, Peary was mired in a controversy that overshadowed his other accomplishments as a skilled civil engineer, natural historian, and expedition leader. Here are a few things you should know about this daring Arctic adventurer.

1. Robert Peary was extremely close to his mother.

Robert Edwin Peary was born May 6, 1856, in Cresson, Pennsylvania, an industrial town in the Allegheny Mountains. His father died when he was 3, and his mother, Mary Wiley Peary, returned with her son to her home state of Maine. As an only child, Peary formed a close bond with his mother, and when he attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, they lived together in rooms off campus. When Peary married Josephine Diebitsch, Mary accompanied the couple on their honeymoon on the Jersey Shore and then moved in with the newlyweds, to Josephine's utter surprise. The explorer confided all of his aspirations to his mother throughout his life. In one prophetic letter to her following his first expedition to Greenland in 1886, he wrote:

"I will next winter be one of the foremost in the highest circles in the capital, and make powerful friends with whom I can shape my future instead of letting it come as it will ... remember, mother, I must have fame, and I cannot reconcile myself to years of commonplace drudgery and a name late in life when I see an opportunity to gain it now."

2. Robert Peary had a side hustle as a taxidermist.

Peary enjoyed a childhood spent outdoors playing sports and studying natural history. After graduating from college with a degree in civil engineering, Peary moved to his mother's hometown of Fryeburg, Maine, to work as a county surveyor. But the county had little need for a surveyor, and to supplement his income, he taxidermied birds. He charged $1.50 for a robin and $1.75 to $2.25 for ducks and hawks.

3. Before he went to the North Pole, Robert Peary went to Nicaragua.

In 1881, Peary was commissioned by the Navy Civil Engineer Corps, which made him a naval officer with a rank equivalent to lieutenant. Three years later, renowned civil engineer Aniceto Menocal picked Peary to lead a field party to survey an area in Nicaragua for a canal linking the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Peary's ability to hack through thick jungle and scale mountains impressed Menocal enough that he hired Peary for a second survey of Nicaragua in 1887, this time with a well-funded, 200-person operation.

4. Robert Peary met Matthew Henson in a Washington, D.C. hat shop.

Though some details of the encounter differ, Peary met his eventual polar partner Matthew Henson at B.H. Stinemetz & Son, a hatter and furrier at 1237 Pennsylvania Avenue. Peary needed a sun helmet for his second trip to Nicaragua. He also needed to hire a valet. The shop's owner recommended his clerk, Henson, who surely impressed Peary with his years of experience on ships. Henson accompanied Peary to Nicaragua and on every Arctic expedition thereafter, including the successful North Pole excursion in 1908-1909.

5. Robert Peary made seven trips to the Arctic.

Peary's first trip to Greenland occurred in 1886 between his two trips to Central America. With a Danish companion, he trekked 100 miles across the Greenland ice cap but had to turn back when food ran low.

During his second and third expeditions (1891-1892 and 1893-1895), Peary, Henson, and company traversed the northern end of the ice sheet and established that Greenland's land did not extend to the North Pole. On his fourth trip (1896-1897), he brought back meteorites for the American Museum of Natural History. Peary's fifth and sixth expeditions (1898-1902 and 1905-1906) tested a feasible route to the North Pole and established relationships with Inughuit communities on which Peary would rely for assistance and supplies. Peary and Henson finally (allegedly) reached the North Pole on the seventh expedition in 1908-1909.

6. Robert Peary's successes in Greenland contrasted with two previous polar disasters.

In 1879, newspaper mogul James Gordon Bennett and Navy commander George Washington DeLong organized an expedition to reach the North Pole via the Bering Strait in a reinforced ship, the Jeannette. After months of besetment, ice crushed the ship and the crew made a desperate escape to Siberia, where all but two members died. Then, Army lieutenant Adolphus Greely led a 25-member magnetic survey expedition to the Canadian high Arctic in 1881. Relief ships failed to reach them for three years. By the time rescue arrived and they returned home, only Greely and five other men had survived starvation. The public's appetite for polar adventure waned until, a few years later, Peary's triumphs in Greenland earned him a heroic reputation and revived interest in the quest for the North Pole.

7. Robert Peary lost eight toes to frostbite.

On the grueling march to establish his camp at Greely's abandoned Fort Conger on the 1898-1902 expedition, Peary suffered a severe case of frostbitten feet. When they reached the hut, Henson took off Peary's footwear and revealed marble-like flesh up to his knees. As Henson removed the commander's socks, eight of Peary's toes popped off with them. As Bradley Robinson writes in the Henson biography Dark Companion, Peary reportedly said, "a few toes aren't much to give to achieve the Pole."

8. Robert Peary's wife Josephine accompanied him to the Arctic when she was eight months pregnant.

Josephine Diebitsch Peary was a formidable adventurer as well [PDF]. Her father Hermann Diebitsch, a Prussian military leader who had immigrated to Washington, D.C., directed the Smithsonian Institution's exchange system. Josephine worked at the Smithsonian as a clerk before marrying Peary in 1888. Bucking social convention, she insisted on accompanying his second expedition in 1891-1892, and in Greenland she managed the day-to-day operation of the base camp, including rationing provisions, bartering goods, hunting, and sewing furs. She even helped defend the men from a walrus attack by reloading their rifles as fast as they shot them.

She also went on Peary's third Greenland trip when she was eight months pregnant, and gave birth to their daughter Marie Ahnighito—dubbed the Snow Baby by newspapers—at their camp. In total, Josephine went to Greenland multiple times, wrote three bestselling books, gave lecture tours, was an honorary member of the American Alpine Club and other organizations, and decorated the family's apartment with narwhal tusks, polar bear skins, fur rugs, and other polar trophies.

9. Matthew Henson saved Robert Peary from a charging musk ox.

In 1895, Peary and Henson scouted a route toward the Pole over the northern edge of Greenland’s ice sheet, just as they had done on their previous trip in 1891-1892. They reached a promontory called Navy Cliff, in extreme northeastern Greenland, but could go no farther. On the way back to their camp on the northwestern coast, they suffered from exhaustion, exposure, and hunger. Their only chance to make it back to camp was to find game.

As described in Dark Companion, Peary and Henson stumbled upon a herd of musk oxen. Henson and Peary killed several, but in his weakened state, Peary shot and missed one. The animal turned around and charged Peary. Henson picked up his gun and pulled the trigger. "Behind [Peary] came the muffled thud of a heavy, fallen thing, like a speeding rock landing in a thick cushion of snow," Bradley Robinson writes in Dark Companion. "Ten feet away lay a heap of brown, shaggy hair half sunken in a snowdrift."

10. Robert Peary absconded with a 30-ton meteorite.

In 1818, explorer John Ross wrote about several meteorites near Greenland's Cape York that served as the Inughuit's only source of metal for tools. In 1896, Peary appropriated the three huge meteorites from their territory. (By the late 19th century, Inughuit had obtained tools via trade and no longer needed the stones for that purpose.) The largest of the three weighed 30 tons and required heavy-duty equipment to load it onto Peary's ship without capsizing the vessel.

Josephine Peary sold the meteorites to the American Museum of Natural History for $40,000 (nearly $1.2 million in today's money). They remain on display in the museum's Hall of Meteorites, where custom-built supports for the heaviest one extend into the bedrock of Manhattan island.

11. Theodore Roosevelt was one of Robert Peary's biggest supporters.

Peary and President Theodore Roosevelt shared a dedication to the strenuous life, and TR—who had served as the assistant secretary of the Navy—helped Peary obtain his multi-year leaves of absence from civil engineering work. "It seems to me that Peary has done valuable work as an Arctic explorer and can do additional work which entitles him to be given every chance by this Government to do such work," Roosevelt wrote to Secretary of the Navy William H. Moody in 1903. Peary repaid the favors by naming his custom-built steamship the S.S. Roosevelt.

In 1906, TR presented the explorer with the National Geographic Society's highest honor, the Hubbard Medal, for Peary's attainment of farthest north. Roosevelt also contributed the introduction to Peary's book about his successful quest for the North Pole.

12. Robert Peary met his nemesis, Frederick Cook, more than a decade before their feud began.

Frederick Cook, a New York City physician, signed up as the surgeon for Peary's second trip to Greenland in 1891-1892. Neither Peary nor Matthew Henson was very impressed with his wilderness skills. Afterwards, Cook joined an expedition to Antarctica and claimed he summited Denali in Alaska, though his climbing partners disputed that feat.

So when Peary and Henson arrived back in Greenland in September 1909 after attaining the North Pole on April 6, they were shocked to hear that Cook had supposedly reached the Pole in spring 1908 and had announced it to the world just five days before Peary had returned to civilization. "[Cook] has not been at the Pole on April 21st, 1908, or at any other time," Peary told newspapers. "He has simply handed the public a gold brick."

From then on, Peary and his family strenuously defended his claim to the Pole. Cook had left his journals and instruments in Greenland in his dash to announce his discovery to the world, and Peary refused to transport them aboard his ship to New York, so it became Cook's word against Peary's. Peary also had the backing of wealthy funders, The New York Times, and the National Geographic Society, who eventually decided the matter in Peary's favor. But the controversy never went away; as late as 2009, the centennial of Peary's claim, historians and explorers were reexamining Peary's records and finding discrepancies in the distances he traveled each day on his way to the Pole. Cook's journals were lost in Greenland, and he spent time in jail for mail fraud. The jury is still out.

13. Robert Peary advocated for a Department of Aeronautics.

Peary was an early proponent of aviation for exploration as well as military defense. As World War I engulfed Europe, he argued for the creation of an air service, the Department of Aeronautics, that would operate alongside the Army and Navy and could then be used for lifesaving coastal patrol. Peary embarked on a 20-city tour to drum up public support for the Aerial Coastal Patrol Fund and raised $250,000 to build stations along the U.S. coast.

The Navy later implemented many of Peary's suggestions, but the tour left the explorer in frail health. He was diagnosed with incurable pernicious anemia and died on February 20, 1920. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, and his gravesite is adorned with a large granite globe inscribed with a motto in Latin, Inveniam viam aut faciam—"I shall find a way or make one."

Additional sources: Dark Companion, The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the Northwest Passage and the North Pole

A version of this story ran in 2020; it has been updated for 2022.