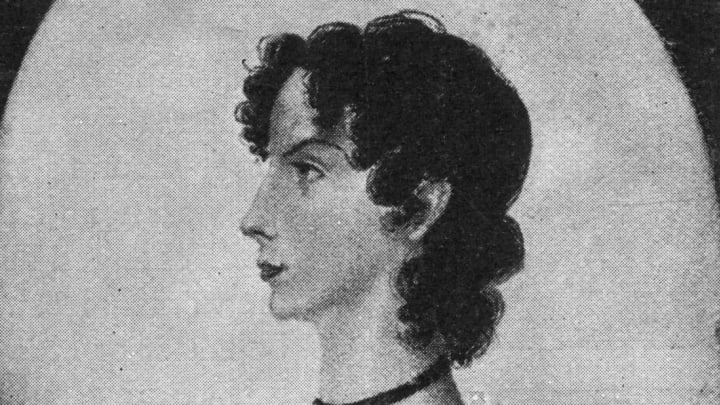

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë are an iconic literary trio—but of the three sisters, Anne has been the least read and, arguably, the least understood. The English critic George Saintsbury once deemed Anne a “pale reflection of her elders”; her own sister, Charlotte, dismissed her as a “gentle, retiring, inexperienced writer.” But such perceptions of Anne as bland and inferior are changing. She worked hard to earn a living, spun vivid tales of an imaginary kingdom, and wrote forcefully about the social oppression of women. To mark the 200th anniversary of her birth in 2020, here are 11 enlightening facts about this underappreciated Brontë sister.

1. Anne Brontë was the youngest of six children.

On January 17, 1820, Anne Brontë was born to Patrick Brontë and his wife Maria Branwell Brontë in the English village of Thornton. She was the couple’s sixth child, and shortly after her birth, the family relocated to the industrial town of Haworth, near the windswept Yorkshire moors so often associated with the Brontë sisters. When Anne was just 20 months old, her mother died, probably of uterine cancer. Maria’s sister, Elizabeth, stepped in to raise the children; Anne was said to be her favorite.

2. Anne and Emily Brontë created a mystical, imaginary realm called Gondal.

Around four years after the death of their mother, the two eldest Brontë sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, also died. The four surviving children immersed themselves in the creation of fictional kingdoms that became the basis for hundreds of prose and poetry works. Charlotte and her brother Branwell crafted tales about the world of Angria, while Emily and Anne—whom one contemporary described as being “inseparable companions”—collaborated on the saga of Gondal.

No prose stories of Gondal survive, but extant poems have allowed scholars to piece together numerous details about this imaginary world. The realm was situated on a large island in the north Pacific, dotted with moorlands, mountains, and woods. Its characters were often swept up in wars and love affairs. Augusta Geraldine Almeda, a beautiful and ruthless heroine who had many lovers, ruled as Gondal’s queen.

3. Anne Brontë worked as a governess—and hated it.

In 1839, hoping to contribute to her family’s strained finances, Anne took a position as a governess for the Ingham family at Blake Hall, a stately mansion in West Yorkshire. She was put in charge of the Inghams’ two eldest children, 6-year-old Cunliffe and 5-year-old Mary. Anne appears to have found the job difficult; summarizing one of Anne’s letters, Charlotte wrote to a friend that her sister’s pupils were “desperate little dunces” who were “excessively indulged and [Anne] is not empowered to inflict any punishment.”

Anne was ultimately dismissed from her job, and she moved on to a position at Thorp Green Hall, where she served as governess for the Robinsons, another wealthy family. Though she worked there for five years, Anne does not appear to have been entirely happy. “[D]uring my stay,” she wrote cryptically in 1845, “I have had some very unpleasant and undreamt-of experience of human nature."

4. Anne Brontë had a dog named Flossy.

In spite of her apparent dissatisfaction at Thorp Green, Anne had a friendly relationship with the three Robinson daughters—Lydia, Elizabeth, and Mary—placed under her instruction. The girls gave Anne a “silky-haired, black and white” dog named Flossy, who, by 1848, was “fatter than ever but still active enough to relish a sheep hunt,” Anne observed in a letter to Charlotte’s friend Ellen Nussey. Kindness to animals was important to Anne; the way her fictional characters treat animals is often a sign of their moral quality.

5. Anne Brontë published poems under the pseudonym Acton Bell.

In 1846, the three Brontë sisters published their first work—a collection of poetry titled Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Charlotte had pushed her sisters to make their writing public, and Emily and Anne agreed to do so only if their names remained secret. They deliberately chose androgynous pseudonyms (Charlotte was “Currer,” Emily was “Ellis,” and Anne was “Acton”) because, as Charlotte once noted, “we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.” But the “Bells’” poetry book was still a flop; it sold only two copies.

6. Anne Brontë’s experiences as a governess inspired her first novel.

Though Agnes Grey, published in 1847, is not strictly autobiographical, it draws on Anne’s early career struggles. The novel’s protagonist, who is also a governess, faces degrading treatment from her employers and abuse from her unruly, violent young charges (one of her pupils enjoys torturing baby birds). With this narrative, Anne sought to highlight the plight of a growing class of governesses, many of whom had little choice but to accept demanding, poorly paid posts because few other professions were considered socially acceptable for middle-class women.

7. Critics were shocked by Anne Brontë’s following book, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

Anne’s second novel, published in 1848, tells the story of a woman’s calamitous marriage to an alcoholic husband and her efforts to escape with her son—a daring plotline for a time when women had no legal status independent of their husbands. The book sold well, and a second edition was published just six weeks after the first. But reviewers were appalled by the novel’s frank depictions of debauchery and marital strife. Wildfell Hall was deemed “coarse,” “revolting” and “brutal.” In her preface to the second edition, Anne pushed back against these criticisms, which she claimed was “more bitter than just.” Her purpose in writing the novel, she explained, was simply “to tell the truth, for truth always conveys its own moral to those who are able to receive it.”

8. Anne Brontë shut down speculation about Acton Bell’s gender.

Concluding her preface to Wildfell Hall, Anne noted that some of her critics “profess[ed] to have discovered” that the author of the novel was a woman. She would not confirm or deny the rumors because, she explained, the subject was irrelevant. “I am satisfied that if a book is a good one,” Anne wrote, “it is so whatever the sex of the author may be.”

9. One of Anne Brontë’s last acts was defending a donkey.

In 1849, Anne was diagnosed with tuberculosis—the same illness that had recently killed both Emily and Branwell. Anne, Charlotte, and Ellen Nussey subsequently set off for Scarborough, a seaside town that Anne had visited and grown to love while accompanying the Robinsons on their holidays there. Upon their arrival, Anne took a ride across the sands in a donkey carriage. “[L]est the poor donkey should be urged by its driver to a greater speed than her tender heart thought right, she took the reins and drove herself,” writes the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, a 19th-century biographer of Charlotte Brontë. Two days later, Anne died at the age of 29.

10. Charlotte Brontë prevented the republication of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

When Charlotte’s publisher proposed reprinting some of the Brontës’ work in 1850, the last surviving sister agreed to the republication of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey. But Wildfell Hall, she opined, was “hardly ... desirable to preserve.” The book’s “choice of subject is a mistake,” Charlotte argued, one that was not consistent with Anne’s “gentle” nature. A publisher nevertheless opted to proceed with the reprint in 1854, shortly before Charlotte died, but Anne’s narrative was extensively edited and rearranged.

The so-called “mutilated texts” of Wildfell Hall underwent a major restoration in 1992, when a complete scholarly edition of the novel was published. Rather than frown upon the unpalatable elements of Anne’s narrative, critics today praise Wildfell Hall’s unflinching depiction of vice and violence—a depiction that contrasts with her sisters’ more romantic portrayals of stormy male characters.

11. It took 164 years to correct an error on Anne Brontë’s grave.

Anne was buried in Scarborough, the only Brontë not to be interred at the family’s vault in Haworth. Charlotte, in spite of her often-patronizing opinions of Anne, was devastated by her sister’s death—and was upset to discover that there were five errors on Anne’s gravestone inscription. Charlotte ordered the stone to be refaced and relettered, but one mistake remained: Anne’s age of death was listed as 28, not 29. In 2013, the Brontë Society corrected the error with a new plaque, which was installed alongside the original and unveiled during a dedication service.