Many of us couldn’t imagine enduring these chilly winter months without down jackets—they keep us warm without weighing a ton. The outerwear was first patented in the U.S. in 1940 by Eddie Bauer; it would become his most iconic and successful product and change the nature of his business, taking it from a local storefront to a nationally known brand. But he might not have come up with the idea if not for a scary near-death experience that occurred in January 1935.

The Little Shop That Could

Bauer was just 21 when he started his business in 1920, renting 15 square feet of space inside another man’s gun shop in downtown Seattle and stringing tennis rackets. According to company historian Colin Berg, Eddie Bauer’s Tennis Shop operated for about a year—just enough time for Bauer to save enough money to open his own storefront.

Bauer’s Sports Shop was a hunting, fishing, and sporting goods store, but Bauer was more than just a merchandiser, he was an outdoorsman, too, and developed gear based on his own needs and the needs of his clients. “If I didn’t trust the equipment, it wasn’t stocked,” he once said. “If I needed equipment that wasn’t available elsewhere, I developed it myself.” If you’ve ever played badminton, for example, you’ve used the shuttlecock Bauer developed and patented.

Bauer backed everything in his shop with a lifetime guarantee—a rare thing in the ‘20s, and something Bauer called “my greatest contribution to the consumer … that guarantee was part of what I sold”—and he only hired people who, like him, were adept at outdoor pursuits. “People knew that if something was in Eddie Bauer’s store, we had personally put it to a rugged test,” he said. His small shop was successful, with a reputation not just for quality goods but also a knowledgeable staff.

For someone who had a passion for hunting and fishing, owning an outfitting shop was the best thing ever: “My business was also my hobby,” Bauer said. “It was like one long vacation. I loved every bit of it.”

A Fateful Trip

The shop might have stayed a small but successful business if not for a fishing trip Bauer took with his friend Red Carlson, a trapper from Alaska, in January 1935. The pair headed to a canyon in the Olympic Peninsula, where they fished for steelhead. That cold, snowy January day, their haul was 100 pounds, and they stripped off their heavy wool mackinaw jackets, climbing out of the canyon in just their wool shirts and long underwear.

The car was a mile away, and the 200- to 300-foot climb out of the river canyon was steep. As they hiked, Bauer—wet from his bag of fish and sweating profusely—began to fall behind his friend. When he reached the top of the canyon, he stopped and leaned against a tree to rest. “He was literally falling asleep on his feet, nodding off,” Berg says. “All that moisture froze in the cold and the snow, and he was getting hypothermic. He was in a bad way.”

Thankfully, Bauer was carrying a revolver. He pulled it out and fired two shots to alert his friend, who came back to get him and helped him to the car. If Bauer had been by himself, he might not have survived. But despite the scary experience, “he wasn’t about to give up winter fishing or hunting,” Berg says. “He realized what he needed was a really breathable, warm jacket that he wouldn’t have to take off when he was working strenuously in the cold.”

Designing with Down

Inspiration struck when Bauer remembered the stories his Uncle Lesser had told him as a kid about his time in the Russian Army during the Russo-Japanese War in Manchuria, before he had emigrated to the United States. Russian officers, Lesser had told Bauer, wore feather-stuffed coats to keep warm in the bitter, bitter cold. And now, Bauer would create a jacket that would allow American outdoorsmen to do the same.

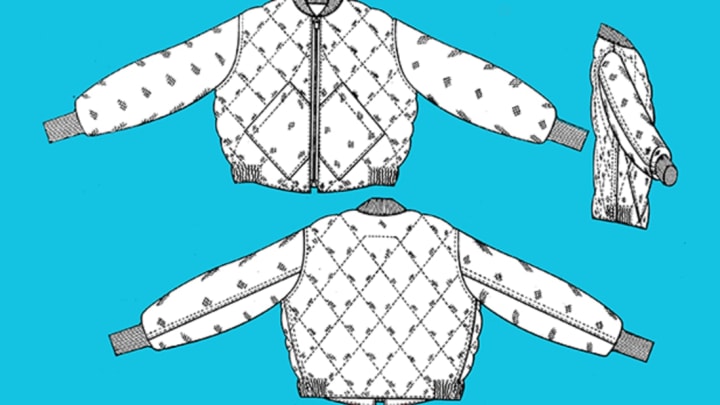

Bauer had worked with feather merchants making flies for his store, so he knew where to get high quality goose down. “He made a pattern for a jacket that he thought would fit him,” Berg says, “and had a local seamstress assemble the prototype.” The resulting jacket was made of high-thread count cotton (which kept the down from escaping) with diamond quilting in the torso (which kept the down in place) and alpaca-lined sleeves.

Bauer took his new outerwear—which he called the Blizzard-Proof Jacket—to his friend Ome Daiber, “a well-known climber at the time, who had also developed some climbing gear,” Berg says. “As a mountaineer himself, he immediately knew the importance and value of it.” Daiber, who had a small manufacturing operation, created the first generation of the jackets for Bauer, who continued to tinker with the design. Then, in 1936, he released a new version of the jacket—he called it the Skyliner—and began to advertise in Field & Stream, American Rifleman, and other hunting and fishing magazines. “He didn’t have a catalog at that point,” Berg says, “so sales happened through mail order and in his shop.”

The jacket proved to be a hit right away, and in 1939, Bauer filed for a patent on his jacket, which he received in 1940. Interestingly, though, the patent didn’t mention down feathers at all. “It could have been insulated with anything as far as the patent was concerned,” Berg says. In fact, none of Bauer’s 11 patents relating to down jackets actually mention down: “They all happened to be insulated with goose down, but it was really the visual quilting pattern that was the patented element.”

Then, in 1942, Bauer made another down jacket that would change his business: the first down-insulated flight jacket of the U.S. Air Force, called the B-9. The jacket—along with the accompanying pants—could keep aviators warm for up to 3 hours at -70 degrees F, and allow them to float with 25 pounds of gear for up to 24 hours. The jacket’s label read “Eddie Bauer, Seattle, U.S.A.,” and when aviators returned home in 1945, they wrote letters asking where they could get more down gear. The servicemen became the company's core customer base when it launched the catalog that same year.

The Skyliner was a key part of his collection from 1936 to 1986 (and was offered again in 1995, 2003, and 2010), and was included in the business’s inaugural 1945 catalog. Testimonials printed in the catalog heaped praise on the product: “I was so pleased with the down Blizzard Proof Jacket, I am ordering three more as presents for my duck hunting friends,” one NYC man wrote. “My husband thinks his down jacket is the best thing that was ever made,” wrote a New Hampshire wife. And, said Mrs. L.E. from Kodiak, Alaska, “I wear it everywhere out of doors. I didn’t buy any woolen underwear, but with this jacket on I certainly don’t need any.” Other satisfied customers say the jacket is “tops” and “worth its weight in gold.”

Lighter Than a Feather

Jackets weren’t the only thing Bauer created with down: In the 1940s, he made comforters, pillows, a “sleeping robe,” and a sleeping bag that was was guaranteed to keep people warm down to temps of -60 degrees F. And though one of Bauer’s early slogans was “Lighter than a feather, warmer than 10 sweaters,” because he wanted to make things as warm as possible, he packed in a lot of down. “The sleeping bag weighed 18 pounds,” Berg says. “The marketing tagline was ‘Built for service you’ll never require.’ But you’d need a dogsled to carry it around.” This was a pattern; the jacket Bauer designed for the 1963 American ascent of Mount Everest had so much down in it that it was rated to -85 degrees F. “I talked to Tim Hornbein from the expedition, and he said, ‘It was in our packs most of the time,’” Berg says. “They couldn’t climb in it, it was so warm.”

Over the years, the designs of Bauer’s down jackets have changed, of course, as new materials became available: The company began blending cotton with nylon in the 1950s, and started using Ripstop nylon in 1958. “It was a little bit like pulling teeth to get Eddie to go that route, because he was afraid that lighter fabric wouldn’t stand up to the durability that was so important to him,” Berg says. (After all, this is a guy who believed that “there can be no compromise of quality when lives depend on … performance.”) His original down jacket, meanwhile, probably wouldn’t look out of place in modern retail stores. “Some of the jackets from the ‘70s and ‘80s seem much more dated, either because of the cut or the color,” Berg says. “But lots of people say you could just take the original off of the form and wear it today.”