On March 4, 1905, Theodore Roosevelt settled in to watch his first inaugural parade. Though he'd been president since the 1901 assassination of William McKinley, this was the first time Roosevelt would get to enjoy the full pomp and ceremony, as Army regiments, West Point cadets, and military bands streamed down Pennsylvania Avenue in the warm March air. Standing in the president's box with his guests, Roosevelt at times clapped and swung his hat in the air to show his appreciation.

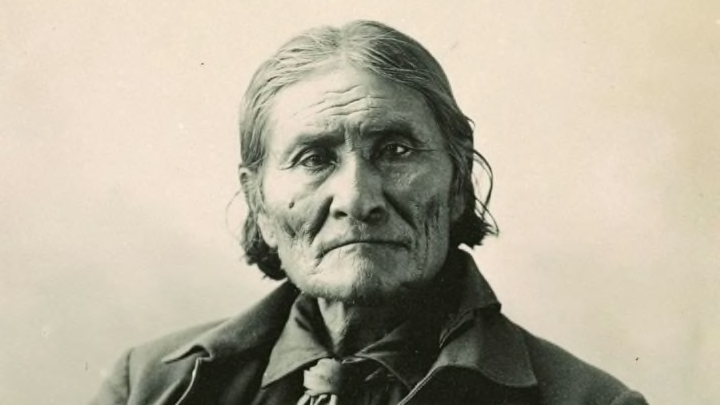

Suddenly, six men on horseback appeared in the procession. They were Native American leaders and warriors, "arrayed in all the glory of feathers and war paint," according to The New York Times report the next day. According to Herman J. Viola, they were “Little Plume, Piegan Blackfoot; Buckskin Charley, Ute; ... Quanah Parker, Comanche; Hollow Horn Bear, Brulé Sioux; and American Horse, Oglala Sioux.” The eldest man, leading the group, was "the once-feared Geronimo," as the Times put it.

The inclusion of the Apache elder was not without controversy. For a quarter-century, Geronimo had attacked Mexican and American troops and civilians, putting up a fierce resistance to settler encroachment. That bloody history—though often sensationalized by press reports—still loomed large during the parade: According to Smithsonian, a member of the 1905 inaugural committee asked Roosevelt, “Why did you select Geronimo to march in your parade, Mr. President? He is the greatest single-handed murderer in American history.”

Roosevelt replied, “I wanted to give the people a good show.”

But unlike the other parade participants, Geronimo wasn't there entirely willingly. He was a prisoner of war. And a few days later, he'd beg Roosevelt for his release.

A Bitter Legacy

Theodore Roosevelt was no friend of America's First Nations. During his childhood, he read books that contained stereotypes of Native Americas, and he and his siblings would, as he wrote in his autobiography, "[play] Indians in too realistic manner by staining ourselves (and incidentally our clothes) in a liberal fashion with poke-cherry juice.” He carried what he had read into adulthood, saying at a lecture in New York while away from his ranch in the Dakotas in the late 19th century that, "I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”

As president, he supported the allotment system, which broke up reservations and forced Native peoples onto smaller, individually-owned lots—essentially remaking traditional land practices in the dominant white image. In his first message to Congress, Roosevelt called the General Allotment Act “a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass.” Roosevelt also favored programs like Pennsylvania's Carlisle Indian Industrial School, established in 1879 to forcibly assimilate Native American children. Students were given new names and clothes, baptized, and forbidden to speak their languages. "In dealing with the Indians our aim should be their ultimate absorption into the body of our people,” Roosevelt said in his second message to Congress.

For most of his life, Geronimo aggressively resisted such attempts at assimilation. Born in the 1820s and named Goyahkla—"One Who Yawns"—near what is now the Arizona-New Mexico border, his life changed forever after his wife, mother, and small children were murdered by Mexican soldiers in the 1850s. Afterwards, Geronimo began attacking any Mexicans he could find; conflict with American settlers soon followed. It is said that his nickname, Geronimo, may have come about after one of his victims screamed for help from Saint Jerome, or Jeronimo/Geronimo in Spanish.

In the 1870s, the Chiricahua Apache were forced onto a reservation in Arizona, but Geronimo and his men repeatedly escaped. Eventually, as Gilbert King writes for Smithsonian, "Badly outnumbered and exhausted by a pursuit that had gone on for 3000 miles ... [Geronimo] finally surrendered to General Nelson A. Miles at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, in 1886 and turned over his Winchester rifle and Sheffield Bowie knife."

The next chapter of Geronimo's life included being shuffled from Florida to Alabama to Fort Sill in the Oklahoma Territory while watching his fellow Apaches die of one disease after another. He was also repeatedly turned into a tourist attraction, appearing at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair and even joining Pawnee Bill’s Wild West show (according to King, under Army guard), where he was billed as "The Worst Indian That Ever Lived."

Geronimo's Tearful Request

The 1905 meeting between Roosevelt, Geronimo, and some of the other Native American men took place a few days after the inauguration, once the crowds had thinned out and things had calmed down a little. Geronimo addressed Roosevelt through an interpreter, calling him "Great Father." According to one contemporary account, Norman Wood’s Lives of Famous Indian Chiefs, he began, "Great Father, I look to you as I look to God. When I see your face I think I see the face of the Great Spirit. I come here to pray to you to be good to me and to my people."

After describing his youthful days on the warpath, which the septuagenarian Geronimo now called foolish, he said, "My heart was bad then, but I did not know it." Now, however, he said, "My heart is good and my talk is straight."

With a tear running down his cheek, he got to the heart of the matter: "Great Father, other Indians have homes where they can live and be happy. I and my people have no homes. The place where we are kept is bad for us. Our cattle can not live in that place. We are sick there and we die. White men are in the country that was my home. ... I pray you to cut the ropes and make me free. Let me die in my own country, an old man who has been punished enough and is free."

According to a March 1905 New York Tribune article, Roosevelt said, “I cannot do so now ... We must wait a while and see how you and your people act. You must not forget that when you were in Arizona you had a bad heart; you killed many of my people; you burned villages; you stole horses and cattle, and were not good Indians.” But it seems at some point, Roosevelt softened—according to Wood, Roosevelt said, “Geronimo, I do not see how I can grant your prayer. You speak truly when you say that you have been foolish. I am glad that you have ceased to commit follies. I am glad that you are trying to live at peace and in friendship with the white people.

"I have no anger in my heart against you," Roosevelt went on. But, he said, "You must remember that there are white people in your old home. It is probable that some of these have bad hearts toward you. If you went back there some of these men might kill you, or make trouble for your people. It is hard for them to forget that you made trouble for them. I should have to interfere between you. There would be more war and more bloodshed. My country has had enough of these troubles."

The president reminded Geronimo that he was not confined indoors in Fort Sill, and allowed to farm, cut timber, and earn money. He promised, "I will confer with the Commissioner and with the Secretary of War about your case, but I do not think I can hold out any hope for you. That is all that I can say, Geronimo, except that I am sorry, and have no feeling against you."

Geronimo's request was never granted. Four years later, in 1909, he died after falling from a horse and developing pneumonia. The Chicago Daily Tribune printed the headline: “Geronimo Now [a] Good Indian."

At least, he was finally free.

Mental Floss has a podcast with iHeartRadio called History Vs., about how your favorite historical figures faced off against their greatest foes. Our first season is all about President Theodore Roosevelt. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts here, and for more TR content, visit the History Vs. site.