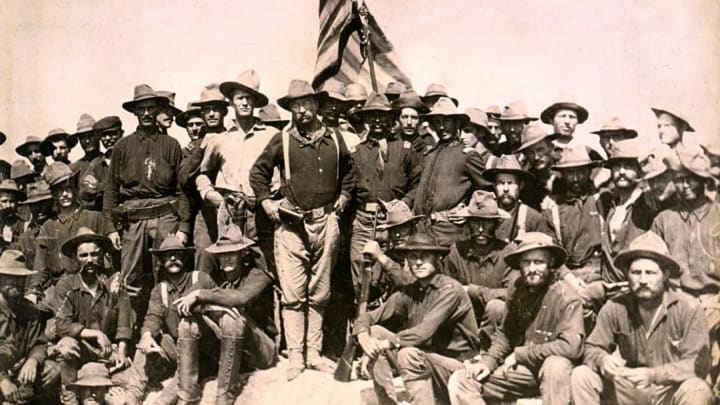

Shortly before hitting the battlefield on July 1, 1898, Theodore Roosevelt had a decision to make. He was about to lead a volunteer cavalry known as the Rough Riders in the Battle of San Juan Heights in Santiago, Cuba, during the Spanish-American War. In protecting both his life and the lives of his men during combat, what sidearm should he choose?

Roosevelt, an avowed arms enthusiast, had an arsenal in his personal collection as well as numerous firearms issued by the U.S. military. The gun he chose to holster on his waist was a Colt Model 1895 .38 caliber double-action revolver with six shots, a blue barrel, and a checkered wood grip. While it may not have been the most formidable weapon at his disposal, it was the most emotionally resonant. The gun, a gift from his brother-in-law, had been retrieved from the wreck of the U.S. battleship Maine, whose sinking had claimed the lives of 266 men and helped usher in the war. He considered the gun a tribute to the sailors and Marines lost in the tragedy.

Now it had become an instrument of that war. In the conflict, Roosevelt aimed his revolver at two opposing soldiers. He missed one. The other was struck—and the wound was fatal. “He doubled up as neatly as a jackrabbit,” Roosevelt later wrote.

Just a few years later, Roosevelt would be president of the United States. The gun remained in his possession until his death in 1919, and eventually came into the care of Sagamore Hill, his onetime home and later a historic site. The Colt occupied a place of honor in the property’s Old Orchard Museum, behind glass and next to the uniform that he wore during the charge.

In April of 1990, a museum employee walked past the display and noticed something unusual. The Colt was gone. The weapon used by the 26th president to kill a man would go missing for 16 years, recovered only under the most unusual of circumstances.

“This poor gun has been through a lot,” Susan Sarna, the museum’s curator, tells Mental Floss. “It was blown up on the Maine, sunk to the bottom, resurrected, goes to San Juan Hill, comes here, then gets stolen—twice.”

According to a 2006 article in Man at Arms magazine by Philip Schreier [PDF], the senior curator at the National Rifle Association’s National Firearms Museum, the Colt has indeed had a hectic life. Manufactured in Hartford, Connecticut, in March 1895, the firearm (serial number 16,334) was delivered from the factory to the U.S. government and wound up on board the USS Maine when the ship was first commissioned in September of that year. The gun was considered ship property and remained on board until February 15, 1898, when the Maine exploded in Havana, Cuba. Many blamed the Spanish for the explosion, and hundreds of men lost their lives.

At the time, Roosevelt’s brother-in-law, William S. Cowles, was heading the U.S. Naval Station. He and his team were sent to the site to inspect the scene. Divers retrieved bodies and other items, including the Colt. Knowing Roosevelt—at the time the Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President William McKinley—was fond of weapons and a genial warmonger, Cowles gave it to him as a gift. While it was perfectly functional, it's clear Cowles intended the Colt to serve to honor the memory of those who had died.

Roosevelt later took it into battle, using it to shoot at enemy forces. (He would earn a posthumous Medal of Honor in 2001 for his actions that day.) Shortly after, the weapon was inscribed to represent its participation in two exceptional events. On one side of the handle:

From the sunken battle ship Maine.

On the other:

July 1st 1898, San Juan, Carried and used by Col. Theodore Roosevelt.

Following Roosevelt’s death in 1919, the Sagamore Hill estate in Oyster Bay, New York, was home to his wife, Edith, until her death in 1948. The property was later donated to the National Park Service in 1963 and became Sagamore Hill National Historic Site. The gun went on display along with many of the former president's other personal effects, eventually settling in the Old Orchard near the uniform he wore during the Battle of San Juan Heights.

In 1963, the Colt came up missing for the first time. With no guard or contemporary security system in place, someone nicked it from the building. Fortunately, it was soon found in the woods behind the museum, slightly rusty from being exposed to the elements but otherwise unharmed. The perpetrator may have gotten spooked after taking off with it and decided to abandon the contraband, but no one had a chance to ask—he or she was never caught.

By April of 1990, the gun and uniform were in a display case borrowed from the American Museum of Natural History. While somewhat of a deterrent, it didn't offer much in the way of security. “The case could be lifted and the lock just popped open,” Sarna says.

Sarna had just started at the museum back then. According to her, the case had either been disturbed by a thief or possibly left open by someone cleaning the display, inviting a probing set of hands. Either way, the gun disappeared—but it wasn’t immediately obvious.

“No one was sure what day it had happened,” she says; the best guess was that the theft had occurred between April 5 and 7. “You’d have to walk into the room it was in and look in the case. If you’re just walking by, you’d see the uniform, but not necessarily the gun.”

It was chief ranger and head of visitor services Raymond Bloomer Jr. and ranger John Foster who discovered the theft one morning. The lock had been popped but the glass was not broken. Sarna and the other employees conducted a search of the property, believing that perhaps someone had taken the Colt out for cleaning. When that failed to produce any results, they notified the National Park Service, which is the first line of investigation for theft on government-owned park property. The NPS, in turn, contacted local authorities in Nassau County and Cove Neck, New York. Soon, the FBI was involved.

Predictably, law enforcement looked at museum employees with a critical eye. “There were all different types of people here interviewing us,” Sarna says. “In museums, the majority of thefts are an inside job.”

Park ranger and museum staffer Scott Gurney, who was hired in 1993, tells Mental Floss that the suspicion cast over employees—none of whom were ever implicated—remained a sore spot. “I found an old police report about it in a desk and asked a ranger about it,” Gurney says. “He got really mad at me and told me not to bring it up again. It was kind of a black eye for the people working there.”

As Sarna and the others set about installing a security system in the museum, the FBI started casting a wide net to locate the weapon, which was uninsured. “It was basically a shoplifting incident,” Robert Wittman, a retired FBI agent in their art crimes division who worked on the case from the mid-1990s on, tells Mental Floss. “It wasn’t all that unusual. In the 1970s and 1980s, lots of small museums were getting hit.” Worse, one of the museum staff working the front desk within view of the display was, according to Gurney, legally blind. The lack of security, Wittman says, was in part because pieces weren’t initially all that valuable on the collector’s market.

The Colt was unique in that it was so readily identifiable. Thanks to the inscriptions, it would invite questions if the thief attempted to sell the weapon. Any attempt to alter it would destroy its cultural value and defeat the purpose of taking it. The FBI sent notices to gun dealers and monitored gun shows in case it turned up. Nothing seemed promising.

“We heard things constantly,” Sarna says. “Someone said it was seen in Europe. Someone else said it was in private hands, or that a collector had it.” Later, when the museum was able to start receiving emails via the burgeoning world of the internet, more tips—all dead ends—came in. Another rumor had the gun being bought during a gun buyback program in Pennsylvania and subsequently destroyed. This one looked promising, as it bore the same serial number. But it turned out to be a different model.

A reward was offered for information leading to the gun’s retrieval, with the amount eventually climbing to $8100. But that still wasn’t sufficient for the gun to surface. “We really had no lines on it,” Wittman says.

Then, in September 2005, Gurney began receiving a series of calls while working in the visitor’s center. The man had a slight speech impediment, he said, or might have been intoxicated. Either way, he told Gurney he knew where the gun was. “He told me it was in a friend’s house, but that he didn’t want to get the friend in trouble.”

The man continued calling, each time refusing to give his name and ignoring Gurney’s suggestion to simply drop the gun in the mail. The man also spoke to Amy Verone, the museum’s chief of cultural resources. He was certain he had seen Theodore Roosevelt’s gun, wrapped in an old sweatshirt in DeLand, Florida. He described the engravings to Verone, who hung up and immediately called the FBI.

After more calls and conversations, including one in which Gurney stressed the historical importance of the weapon, the caller eventually relented and gave his information to the FBI. A mechanical designer by trade, Andy Anderson, then 59, said he had seen the gun the previous summer. It had been shown to him by his girlfriend, who knew Anderson was a history buff. She told Anderson her ex-husband had originally owned the firearm. It had been in a closet wrapped in a sweatshirt before winding up under a seat in the woman’s mini-van, possibly obscured by a dish towel. Presumably, her ex had been the one who had stolen it back while visiting the museum as a New York resident in 1990.

After Anderson contacted Sagamore Hill, FBI agents were dispatched from the Daytona Beach office to DeLand to question Anderson. He obtained the revolver from his girlfriend and handed it over, though he apparently tried to convince the FBI to let him return the weapon without disclosing the thief’s identity. The FBI didn’t agree to an anonymous handoff, however, and in November 2006 the ex-husband, a 55-year-old postal employee whom we’ll refer to as Anthony T., was charged with a misdemeanor in U.S. District Court in Central Islip, New York.

Wittman remembers that the split between Anthony T. and his wife had been acrimonious and that she had no involvement in the theft. “We were not going to charge her with possession of stolen property,” he says.

Wittman went to Florida to pick up the Colt and brought it back to the Philadelphia FBI offices, where it was secured until prosecutors authorized its return to Sagamore Hill on June 14, 2006. Schreier, the NRA museum’s senior curator, arrived at Sagamore Hill with Wittman, FBI Assistant Director in Charge in New York Mark Mershon, and Robert Goldman, the onetime U.S. assistant attorney and art crime team member who was himself a Roosevelt collector and had doggedly pursued the case for years. When Schreier confirmed its authenticity, the gun was formally turned back over.

There was no reasonable defense for Anthony T. In November of that year, he pled guilty to stealing the Colt. While he was eligible for up to 90 days in jail and a $500 fine, Anthony T. received two years of probation along with the financial penalty and 50 hours of community service. According to Wittman, cases of this sort are based in part on the dollar value of the object stolen—the weapon was valued at $250,000 to $500,000—not necessarily its historical value. “The sentencing may not be commensurate with the history,” Wittman says.

From that perspective, the Colt takes on far greater meaning. It was used in a battle that cemented Roosevelt’s reputation as a leader, one credited with helping bolster his national profile. It was used in commission in the death of a human being, giving it a weight and history more than the sum of its metal parts.

“It’s looked at as one of his greatest triumphs,” Sarna says of the Rough Riders and the U.S. victory in the 1898 conflict. “It brought us into a new century and out of isolationism.”

It’s once more on display at Sagamore Hill, this time under far better security and surveillance. (Though the museum is still vulnerable to heists: a reproduction hairbrush was recently swiped.) Sarna, who wasn’t sure if she would ever see the Colt again, is glad to see it where it belongs.

“Thank goodness they got divorced,” she says.

It’s not publicly known why Anthony T. felt compelled to take the Colt. Wittman describes it as a crime of opportunity, not likely one that was planned. After the plea, Anthony T. was let go from his job, and his current whereabouts are unknown. Prosecutors called it a mistake in judgment.

Anderson, the tipster, lamented any of it had to happen. “We’re talking about a mistake he made 16 years ago,” Anderson told the Orlando Sentinel in November 2006. “I have no regrets, but I never meant to cause trouble. I wish Anthony the best.”

If Anthony T. was an admirer of Roosevelt’s, he might find some poetic peace in the fact that he pled guilty to violating the American Antiquities Act of 1906, which was instituted to prevent theft of an object of antiquity on property owned by the government.

That bill was signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt.