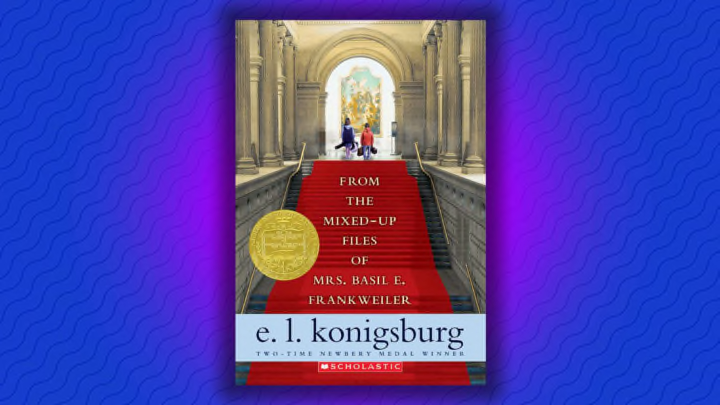

This beloved children’s book—about a girl and her younger brother who run away to New York City, live in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and try to solve the mystery of who sculpted its newest statue—is a staple of elementary school reading lists. Here are a few things you might not have known about From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.

1. Author E.L. Konigsburg got the idea for From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler from a visit to the Met.

A kernel of the idea for From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler began with a piece of popcorn on a chair. Konigsburg wrote later that she was visiting the Met with her three children, going through the period rooms on the museum’s first floor “when I spotted a single piece of popcorn on the seat of a blue silk chair. There was a velvet rope across the doorway of the room. How had that lonely piece of popcorn arrived on the seat of that blue silk chair? Had someone sneaked in one night—it could not have happened during the day—slipped behind the barrier, sat in that chair, and snacked on popcorn? For a long time after leaving the museum that day, I thought about that piece of popcorn on the blue silk chair and how it got there."

2. A New York Times article also provided inspiration.

The next important piece of the puzzle came in October of 1965, when Konigsburg read an article in the New York Times about a bust the Museum had bought at an auction, titled “A $225 Sculpture May be a Master’s Worth $500,000.” One dealer guessed that the sculpture, which had come from the estate of Mrs. A. Hamilton Rice, had been created by Leonardo da Vinci or Andrea del Verrocchio. James J. Rorimer, director of the museum, was delighted, according to the article, and said, “I’m overjoyed. It looks to me like a great bargain.” Two other articles about the bust followed, and there was such a media frenzy that, according to John Goldsmith Phillips, Chairman of Western European Arts, the sculpture was brought out of the auction house “in a box labeled by chance ‘musical instruments,’ in this manner passing unnoticed through a group of reporters who were gathered there.”

3. The final inspiration for From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler was a picnic.

The next summer, Konigsburg and her family went on vacation to Yellowstone Park. One day, she suggested a picnic, but they couldn’t find a picnic table, “so when we came to a clearing in the woods, I suggested that we eat there,” she wrote later. “We all crouched slightly above the ground and spread out our meal. Then the complaints began. ... This was hardly roughing it, and yet my small group could think of nothing but the discomfort.” Konigsburg realized her kids could never become uncivilized. If they were ever to run away, “they would never consider a place less civilized than their suburban home. They would want all those conveniences plus a few extra dashes of luxury. Probably, they wouldn’t consider a place even a smidgen less elegant than The Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

And that, she said, is when she started thinking about hiding in the Museum:

“They could hide there if they found a way to escape the guards and left no traces—no popcorn on chairs—no traces at all. The Museum had everything. … And while they were there—while they were ‘insiders’ in every sense of the word—they could discover the secret of the mysterious statue that the Museum had bought for $225. And then, I thought, while away from home, they could also learn a much more important secret: how to be different inside their suburban crust—that is, different on the inside, where it counts.”

4. Konigsburg drew the illustrations for the book—and her kids posed for the characters.

“The illustrations probably come from the kindergartener who lives inside, somewhere inside of me, who says, ‘Silly, don’t you know that it is called show and tell? Hold up and show and then tell,’” Konigsburg said in 1968. “I have to show how Mrs. Frankweiler looks … Besides, I like to draw, and I like to complete things, and doing the illustrations answers these simple needs.”

She used her children as models for the illustrations. Konigsburg’s daughter Laurie, then 12, posed for Claudia, while her son Ross, 11, posed for Jamie. Her son Paul, she wrote in an afterword to the 35th anniversary edition of the book, “is the young man sitting in the front of the bus in the picture facing page 13.” According to The New York Times, Konigsburg “herded the kids upstairs, took pictures of them in various poses, then made drawings from the pictures.”

5. Konisgburg and her kids made many research trips to the Met.

“Many, many trips,” she wrote later. “And we took pictures. We were allowed to use a Polaroid camera, but we were not allowed to use a flash. Laurie and Ross posed in front of the various objects that we could get close to. However, they did not take a bath in the fountain. I took pictures of the restaurant fountain and pictures of my children at home and combined them in the drawing.”

6. Mrs. Frankweiler was based on two women.

Mrs. Frankweiler’s personality was based on Olga Pratt, the headmistress of Bartram’s School, where Konigsburg taught; the writer said that Pratt was “a matter-of-fact person. Kind, but firm.” The illustrated Mrs. Frankweiler was based on Anita Brougham, who lived in Konigsburg’s apartment building. “One day in the elevator I asked if she would pose for me,” Konigsburg said. “And she did.”

7. From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler was acquired by the woman who would become Konigsburg’s “forever editor.”

Konigsburg was an unpublished mother of three when she submitted the manuscript for her first book, Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley and Me, Elizabeth, to Atheneum Books. She chose the imprint, according to a February 28, 1968 New York Times article, because "a couple of years ago it had [a] Newbery Award winner." While Jennifer, Hecate... was with the publisher, and her son Ross was at school, Konigsburg started, and finished, From the Mixed-Up Files (she wrote the entire manuscript in longhand). Atheneum editor Jean E. Karl wrote to Konigsburg in July 1966 telling her how much she wanted the book:

“Since you came in with FROM THE MIXED-UP FILES OF MRS. BASIL E. FRANKWEILER, I have found myself chuckling over it more than once. I have read it myself only once, but the memory of the incidents comes up every once in awhile. “I really do want this book. I will be sending you a contract very shortly. I have some suggestions that I think will make it even better, but don’t want to make them until I have had a chance to read it through again. You will be hearing from me shortly.”

Karl would go on to edit all of Konigsburg’s books; the writer called her “my forever editor.”

8. From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler won a Newbery Medal.

Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley and Me, Elizabeth, which was also released in 1967, was an honor book, making Konigsburg the only author who received both the Newbery Medal and an honor book in the same year. In her speech, Konigsburg thanked her editor, Jean Karl, the Newbery committee members, and “All of you ... for giving me something that allows me to go home like Claudia—different on the inside where it counts.”

9. One reviewer was offended by the book’s reference to drugs …

In one part of From the Mixed-Up Files, Jamie spots a candy bar on the stairs of the Donnell Library in New York and picks it up; Claudia tells him not to, because “it’s probably poisoned or filled with marijuana, so you’ll eat it and become either dead or a dope addict. … Someone put it there on purpose. Someone who pushes dope.”

In TalkTalk: A Children’s Book Author Speaks to Grown-Ups, Konigsburg wrote about a reviewer who didn’t like “a gratuitous reference to drugs in an otherwise pleasing story.” Konisburg then wonders what that reviewer would have thought about a letter she received in 1993 from a reader who wrote,

“I liked when Claudia wanted to be a heroine. ... I thought that was only a drug. But now I know it means a girl hero.”

“Would the reviewer, who in 1967 was offended by my brief reference to drugs, be equally offended by a young reader who in 1993 needs an explanation for heroine but not heroin?” she wondered. “Or would the same reviewer perhaps have a daughter or granddaughter who in 1993 is a member of the campus feminist group Womyn of Antioch and is offended by Claudia’s thinking of herself as a heroine instead of a hero? For every one of us who says actress or hostess or priestess, there is a word watcher, ready with Wite-Out and caret, who believes that, be they male or female, the correct words are actor, host, and priest. There has always been something to offend someone, and there always will be.”

10. … And one reader didn’t think a particular part of the plot was realistic.

The reader “wrote me a letter scolding me for writing that two kids could live on twenty-four dollars and forty-three cents for a whole week in New York City,” Konigsburg wrote in the 35th anniversary edition of the book. That reader was the only one to complain, though: “Most readers focus on their rent-free accommodation in the museum and recognize that these details—accurate for their time—are the verisimilitude that allow Claudia and Jamie to live beyond the exact details of life in 1967.”

11. One publisher wanted to adapt some of From The Mixed-Up Files for a textbook—but it didn’t work out.

At one point, Karl passed along to Konigsburg a request from a textbook publisher to use Chapter 3 of From the Mixed-Up Files in a textbook. Konigsburg published the three-way correspondence between Karl, herself, and the textbook editor in TalkTalk. “I am planning to follow your story with a photo essay/article on a very exciting Children’s Museum in Connecticut,” the textbook editor wrote. “It is my hope that the two pieces together will give children a new, most positive approach to museums, both traditional and experimental.”

Konigsburg was fine with the publisher using a part of the book “if they used the material as I have edited it per the request in their letter,” she wrote back to Karl. “I have cut out as much as they have in the interest of space without destroying the characterization of the two children and without leaving information dangling in the manner they did on pages 3 and 6 of their copy.”

The letter that Karl received back, she wrote to Konigsburg, was “ridiculous. I would like to say to them ‘Go fly a kite.’” The issue? The textbook publisher wasn’t OK with the children standing on the bathroom toilets to evade detection while the Museum was being closed. In a phone call, the editor told Konigsburg that “they were afraid they would get irate letters from people … [and] that some child might read about standing on the toilets and try it and fall in.” Konigsburg said that was nonsense, and that if they wanted to use the chapter, that part had to stay in. Later, she received a letter from Karl noting, “You will be interested to know that since you will not allow the children not to stand on the toilets [the publisher] has decided not to use the selection. I think they are being absurd and hope it doesn’t bother you too much that they won’t be using it."

12. There was a sequel … of sorts.

When From the Mixed-Up Files won the Newbery in 1968, Konigsberg wrote a mini-sequel to hand out to the attendees of the banquet. In it, Jamie is writing a letter (in pencil, to Claudia’s horror, because he’s renting his pen to Bruce) and tells Claudia that he’s writing to Mrs. Frankweiler because she put everything they told her “into a book, and it won the Newbery Medal. … I figure that if the medal is gold, she better cut me in. I’ve been broke ever since we left her place,” he says.

Despite many letters from readers asking for one, this, Konigsburg declared in the 35th anniversary edition of From the Mixed-Up Files, “is the only sequel I’ll ever write. I won’t write another, for there is no something-more to tell about Claudia Kincaid and Jamie and Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. They are as they were, and as I hope they will be for the next thirty-five years.”

13. From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler was made into a movie.

Two movies, actually. The 1973 big-screen adaptation starred Ingrid Bergman as Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler; Sally Prager played Claudia, and Johnny Doran played Jamie. According to a New York Times article about the movie, the Met, which closed for a day to accommodate filming, had “never before given over its premises to a commercial film.” (The movie was called The Hideaways for home video.) The book was also adapted in a TV movie in 1995, with Lauren Bacall playing Mrs. Frankweiler.

14. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has changed a lot since the Book was Published …

The bed that Claudia and Jamie slept in—where Amy Robsart, wife of Elizabeth I’s favorite, Lord Robert Dudley, was allegedly murdered in 1560—has been dismantled, and the Fountain of Muses, where the kids bathed, is no longer on display. The chapel where Jamie and Claudia said their prayers was closed in 2001. The museum’s entrance has been given a facelift, and it’s no longer free to get in as it was when Jamie and Claudia stayed there (the price of admission is up to the visitor if they live in New York State or are students in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut).

15. … But The Met's staff still gets asked lots of questions about the book.

In fact, it gets so many questions that it created a special issue of Museum Kids entirely devoted to From the Mixed-Up Files [PDF]. After making it very clear that kids can’t camp out in the Met like Jamie and Claudia did, the issue guides kids to spots featured in the book—including the Egyptian galleries—and the Room from the Hotel de Varengeville in Paris, where Konigsburg saw the piece of popcorn on the blue silk chair.

16. The Museum doesn’t actually own a statue by Michelangelo ...

But it does own some of his drawings, including Studies for the Libyan Sibyl, which Michelangelo drew to prepare for painting the Sistine Chapel. According to the From the Mixed-Up Files issue of Museum Kids, “The drawing isn’t on view very often because, over time, light will darken the paper and you wouldn’t be able to see the red chalk that the artist used to draw the picture. The drawing is kept in a black box that keeps out moisture, dust, and air.”

17. … And the mystery of its bargain sculpture has been solved.

The Met’s bargain sculpture was made of plaster with a stucco surface; it is believed to be a cast of one of Verrocchio’s sculptures, The Lady with the Primroses. Curators think it was made by Leonardo da Vinci around 1475, when he was working in Verrocchio’s workshop [PDF].

A version of this story ran in 2014; it has been updated for 2021.