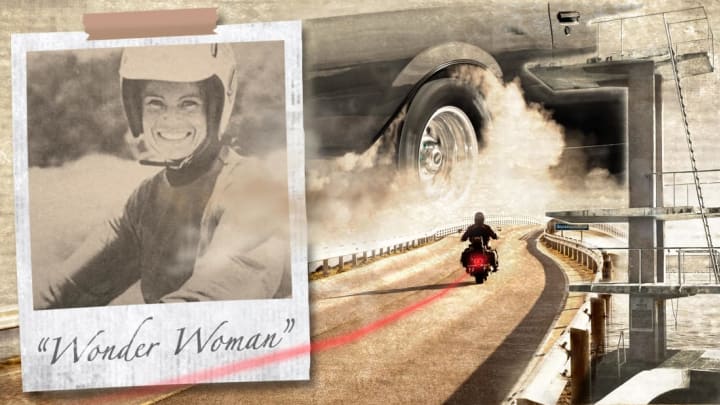

Kitty O’Neil could do it all. A stuntwoman, drag racer, and diver, the legendary daredevil's skills were once described by the Chicago Tribune as “full and partial engulfment in fire; swimming; diving; water skiing; scuba diving; horse falls, jumps, drags, and transfers; high falls into an air bag or water; car rolls; cannon-fired car driving; motorcycle racing; speed, drag, sail, and power boat handling; fight routines; gymnastics; snow skiing; jet skiing; sky diving; ice skating; golf; tennis; track and field; 10-speed bike racing; and hang gliding.”

During her lifetime, O’Neil set 22 speed records on both the land and sea—including the women’s land speed record of 512 mph, which remains unmatched to this day. Through it all, she battled casual sexism and ableism, as she was often not only the lone woman in the room, but the lone deaf person on the drag strip or movie set.

"It Wasn't Scary Enough for Me"

O’Neil was born on March 24, 1946, in Corpus Christi, Texas. Her father, John, was an Air Force pilot and oil driller, while her mother, Patsy, was a homemaker. When she was just a few months old, O’Neil contracted mumps, measles, and smallpox, an onslaught of illness that damaged her nerves and caused her to lose her hearing. Patsy, who had packed her in ice during the worst of the fever, went back to school for speech pathology so she could teach her daughter how to read lips and form words. She placed the young girl’s hand on her throat as she spoke, allowing her to feel the vibrations of her vocal cords.

Feeling those sensations helped Kitty learn to talk, while the sensations associated with engines would teach her something else. At the age of 4, O’Neil convinced her father to let her ride atop the lawn mower in what would be a transformative experience. “I could feel the vibrations,” she told the Associated Press. “That’s what got me into racing. When I race, I feel the vibrations.”

But racing wasn’t her first thrill ride. As a teenager, O’Neil showed such an aptitude for diving that Patsy decided to move the family to Anaheim, California, where O’Neil could train with the two-time Olympic gold medalist Sammy Lee. She was on her way to the qualifying rounds for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics when she broke her wrist, eliminating her from consideration. Soon after, she contracted spinal meningitis. Her doctors worried she wouldn’t walk again.

She recovered, but found she was no longer interested in diving. “I gave it up because it wasn’t scary enough for me,” she told the Chicago Tribune.

Motorcycle racing proved to be a better adrenaline rush, so she began entering competitions along the West Coast. It was at one of those races that she met another speedster named Ronald “Duffy” Hambleton, who offered his assistance after O’Neil crashed her bike, severing two fingers. Once she had gotten stitched up, the pair began a professional and romantic relationship. O’Neil moved onto a 40-acre ranch in Fillmore, California, with Hambleton and his two children from a previous relationship.

Hambleton would act as O’Neil’s manager, often speaking to the press for her after stunts or record attempts. However, O’Neil later alleged that he stole money from her and physically abused her during their partnership. In 1988, a Star Tribune reporter would describe O’Neil’s scrapbooks as containing a photo of Hambleton with his face scratched out; she had also written “not true” in the margins of newspaper clippings touting his profound impact on her success.

The Need for Speed

O’Neil wanted to go fast and she didn’t care how. So she expanded her scope beyond motorcycles, setting a new women’s water skiing record in 1970 with a speed of 104.85 mph. Her national breakout arrived six years later, when she drove a skinny three-wheel rocket car into the Alvord Desert. The hydrogen peroxide-powered vehicle was dubbed “The Motivator,” and it was the work of William Fredrick, a designer who normally created cars for movie and TV stunts. When O’Neil got behind the wheel of The Motivator, she quickly smashed the women’s land speed record. Her average speed was 512 mph, over 1.5 times faster than the previous 321 mph record held by Lee Breedlove since 1965.

She believed she could beat the men’s record of 631.4 mph, too, which should’ve been great news for her entire team. Fredrick and his corporate sponsors were gunning for a new record, and O'Neil had already reportedly hit a maximum speed of 618 mph in her initial run. But before she could take The Motivator for a second spin, she was ordered out of the car.

As O’Neil would discover, she had only been contracted to beat the women’s record. Marvin Glass & Associates, the toy company that owned the rights to the vehicle, wanted Hollywood stuntman Hal Needham to break the men’s record. The company claimed it was purely a business decision, as they had a Needham action figure in the works. But according to Hambleton, the company reps had said it would be “unbecoming and degrading for a woman to set a land speed record.”

“It really hurts,” O’Neil told UPI reporters as she choked back tears. “I wanted to do it again. I had a good feeling.” She earned the immediate support of the men’s record holder, Gary Gabelich, who called the whole incident “ridiculous” and “kind of silly.” She and Hambleton tried to sue for her right to another attempt, but she wouldn’t get a second ride in The Motivator. Needham wouldn’t break the record, either, as a storm dampened his chances. Not that he was especially polite about it.

“Hell, you’re not talking about sports when you’re talking about land speed records,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “It doesn’t take any God-given talent … even a good, smart chimpanzee could probably do it. Probably better—because he wouldn’t be worried about dying.”

As the messy legal battle dragged on, O’Neil focused on her budding career in stunt work. According to The New York Times, she completed her first stunt in March of 1976, when she zipped up a flame-resistant Nomex suit and let someone set her on fire. For her second job, she rolled a car, which was practically a personal hobby. (She liked to tell people she rolled her mother’s car when she was 16, the day she got her driver’s license.) O’Neil eventually became Lynda Carter’s stunt double on Wonder Woman, where she famously leapt 127 feet off a hotel roof onto an air bag below. “If I hadn’t hit the center of the bag, I probably would have been killed,” she told The Washington Post in 1979.

Her work earned her a place in Stunts Unlimited, the selective trade group that had, until that point, only admitted men. O’Neil continued racking up credits with gigs on The Bionic Woman, Smokey and the Bandit II, and The Blues Brothers. Although few stunt doubles achieve name recognition, O’Neil was a media darling who inspired her own 1979 TV movie starring Stockard Channing and a Barbie in her trademark yellow jumpsuit.

A Pioneer's Legacy

But by 1982, feeling burned out after watching the toll the work had taken on colleagues, O'Neil decided she was finished. She retired from the business at the age of 36, packing up and leaving Los Angeles entirely. She wound up in Minneapolis and then in Eureka, South Dakota, a town with a population of fewer than 1000 people. She would live out the rest of her days there, eventually dying of pneumonia in 2018 at the age of 72.

O’Neil lived her life as a never-ending challenge—to go faster, jump higher, do better. She always said that her lack of hearing helped her concentrate, eliminating any fear she might’ve felt over the prospect of breaking the sound barrier, let alone self-immolation.

“When I was 18, I was told I couldn’t get a job because I was deaf,” she told a group of deaf students at the Holy Trinity School in Chicago. “But I said someday I’m going to be famous in sports, to show them I can do anything.”

O’Neil did exactly that. Over her the course of perilous career, she carved out a name for herself in a space that was often openly hostile towards her, setting records and making it impossible for anyone who doubted her to catch up.