Since Julia Child created and began hosting the television cooking show The French Chef in 1963, making finer fare more accessible and feasible for the general public, it seems as if the celebrity chef has been a staple of pop culture—with interest in the culinary masters reaching peak popularity in today's Food Network age. But before Anthony Bourdain and Tom Colicchio, before Martha Stewart and Lidia Bastianich, and even before Julia Child, how did cooks become chefs and how did chefs become famous? Who exactly were the first “celebrity chefs”? We’re going to start at the very beginning…

1. Guillaume Tirel (1310-1395)

Guillaume Tirel, also known as Taillevent or “slicewind,” was the first documented cook to be given the title “Master Chef,” thanks to his cookbook of recipes for medieval cuisine of Northern France, Le Viandeir. By 16, Taillevent was named queux (head chef) to King Philip VI and continued to work as queux for Dauphin de Viennois and the Duke of Normandy. His interpretation of French food set the gold standard for hundreds of years, until Catherine de Medici brought in new ideas and new chefs. Above all, Tirel revolutionized the use of spices in dishes.

2. Martino da Como (born around 1430)

Martino da Como has garnered many titles thanks to his culinary talents: Maestro Martino, the Prince of Cooks, and the Leonardo da Vinci of cooks. The humanist philosopher and Vatican librarian Bartolomeo Sacchi described Maestro Martino as “the prince of cooks from whom I learned all about cooking.”

Maestro Martino traveled to Milan to refine his culinary techniques and cook for royalty, but he only gained fame and notoriety once he was chosen for the Vatican kitchen. There, he used older, traditional recipes to inspire new and modern renditions on his plates. He was the first known chef to take on this (now very popular) approach to cooking.

3. Francois Vatel (1631-1671)

Poor Francois Vatel. His passions for perfecting a 2000-person banquet in honor of King Louis XIV led to Vatel taking his own life. After not sleeping for almost 12 nights in preparation of the party and some trouble with celebratory fireworks in a foggy sky, Vatel was so overwhelmed by news of a delay in his fish delivery that he ran into the sword given to him by the royal court.

In a somewhat comical twist, immediately after Vatel’s suicide, the fish delivery started rushing in. This story became infamous among aristocrats and royalty of the time.

4. Antoine Parmentier (1737-1813)

Antoine Parmentier was not so much known as a chef, but more as a promoter of certain foods. While captive as a prisoner of war in Prussia, Parmentier was forced to eat potatoes, known only in his home land of France as hog feed. When released, he performed experiments on the chemistry of the potato and learned of its nutritional value, then went on to become an advocate of the tuber. Many potato-based dishes have been named after him, including hachis Parmentier, which is similar to a shepherd’s pie.

5. Antoine Beauvilliers (1754-1817)

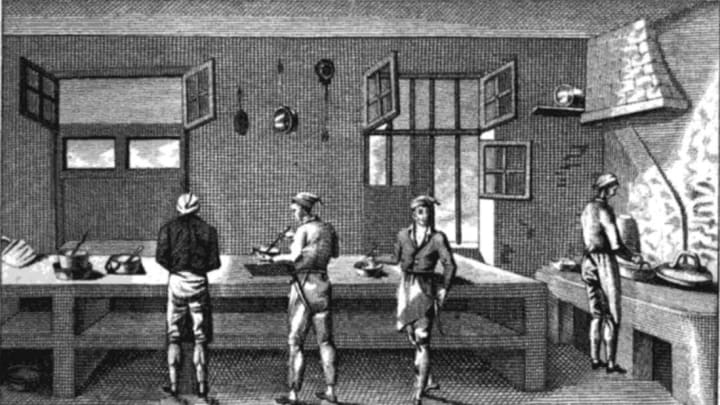

Antoine Beauvilliers may have been the chef to truly pave the way for all the badass, rebel chefs to come. He started working as a kitchen boy before rising to the post of chef for the future king Louis XVIII. In 1782, he became one of the first known restaurateurs, opening Le Grande Taverne de Londres in Paris.

Beauvilliers, who had a flair for combining all senses in the dining experience, was described by the famous gastronome Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin as “the first to combine the four essentials of an elegant room, smart waiters, a choice cellar, and superior cooking.” The politicians of the time respected and trusted Beauvilliers so much that they rendezvoused at Le Grande. This, unfortunately, implicated Beauvilliers in illegal activities, and the restaurant was shut down. A guard supposedly saved his life, saying, “We can’t cut off a head with such refined taste buds.” Later, Beauvilliers wrote a book that became the defining French cookbook of the age.

6. Marie Antoine Careme (1784-1833)

Although the French could boast many celebrity chefs before him, Marie Antoine Careme solidified his stance in culinary history as the inventor of excessive grande cuisine. He not only did away with silly, inedible garnishes that were popular on plates at the time by instead garnishing meat with meat and fish with fish, but he also made the cold buffet famous, because he believed cooking killed the natural flavor of food. Still traditionalized in culinary practices today, Careme divided French sauces into four different groups (Georges Auguste Escoffier wouldn't add the fifth mother sauce until much later); his interest in architecture also helped to popularize the art of pastry construction by creating extravagant, edible centerpieces.

7. Alexis Soyer (1810-1858)

Cooking today would not be nearly as easy without the inventions of Victorian chef Alexis Soyer. As chef de cuisine of the Reform Club, he installed an oven with adjustable temperatures and developed a technique to cook with gas.

Among many other achievements, Soyer cooked a celebratory breakfast for 2000 people the morning of Queen Victoria’s crowning; the lamb cutlets dish he prepared still appears on the Club’s menu today. Soyer was also arguably the inventor of the soup kitchen, which he created during the Great Irish Famine.

8. Xavier Marel Boulestin (1878-1943)

Dabbling in the realms of interior design, wine, pottery, writing and candle-shades eventually led Xavier Marel Boulestin to be contracted by a British publishing company to write a French cookbook. Simple French Cooking for the English Home was published to much success in 1923.

Boulestin, although never really even knowing how to cook, quickly became the go-to man of the wealthy for cooking lessons; he even taught Winston Churchill a few recipes. His restaurant, Restaurant Boulestin, was known as the most expensive restaurant in London in the late 1920s. And, in a hint of what was to come, Boulestin was likely the first TV chef; he gave cooking demonstrations on BBC’s A Scratch Meal with Marcel Boulestin twice monthly from 1937 to 1939.