When Charles Darwin visited the Galapagos Islands on the HMS Beagle in the 1830s, it wasn’t just finches he was fascinated by; the naturalist also got a kick out of the island chain’s giant tortoises. “I was always amused, when overtaking one of these great monsters as it was quietly pacing along, to see how suddenly, the instant I passed, it would draw in its head and legs, and uttering a deep hiss fall to the ground with a heavy sound, as if struck dead,” he wrote later. “I frequently got on their backs, and then, upon giving a few raps on the hinder part of the shell, they would rise up and walk away;—but I found it very difficult to keep my balance.”

But riding tortoises wasn't what most men who visited the Galapagos, which sits off the coast of Ecuador, were after. Sailors, whalers, buccaneers, and fur traders who passed through saw two sorely needed commodities—meat and oil—in the slow-moving reptiles (“the flesh of this animal is largely employed, both fresh and salted; and a beautifully clear oil is prepared from the fat,” Darwin noted), and brought them on board alive to slaughter as they made their way home. Before man interfered, more than 200,000 giant tortoises lived in the Galapagos; today, an estimated 20,000 tortoises survive. (Invasive species brought by boat—including goats and rats—further decimated tortoise habitat.) According to the Galapagos Conservancy, the 23-square-mile Pinta Island was the first landfall after a long voyage at sea and the last on the way back, and likely bore the brunt of the hunting. By the early 1900s, scientists believed that four of 14 species had gone extinct—including Pinta’s Chelonoidis abingdoni.

That changed in November 1971, when Hungarian scientist József Vágvölgyi reported something extraordinary: While on Pinta studying snails, he had seen a C. abingdoni tortoise ambling across the island. The next year, Galapagos National Park rangers moved the male tortoise to the Charles Darwin Research Station on nearby Santa Cruz Island, where scientists hoped they might save C. abingdoni through mating him with similar species. Soon, the American media had dubbed him Lonesome George, after a character created by American comedian George Gobel. He lived at the Tortoise Breeding and Rearing Center for 40 years, and though George did mate with at least three female tortoises, none of the unions resulted in viable offspring. Still, the tortoise delighted visitors and served as a symbol to the people of the Galapagos. He was called the rarest creature in the world.

Lonesome George in 2005 at the Charles Darwin Research Station. Photo courtesy of the Charles Darwin Foundation/Allison Llerena.

Though George was estimated to be more than 100 years old in 2012, no one expected him to die; giant tortoises can live up to 200 years. But on Sunday, June 24, 2012, George’s long-time keeper, Fausto Llerena, had found him "stretched out in the direction of his watering hole with no signs of life." (A necropsy determined George died of natural causes.)

Eleanor Sterling, chief conservation scientist at the American Museum of Natural History’s Center for Biodiversity & Conservation, was in the islands for an education and outreach workshop with colleagues at the Galapagos Conservancy, the Galapagos National Park, and State University of New York (SUNY) when they got the news. The sadness on the islands was palpable. "He had been a part of their being, a part of their communities," Sterling tells mental_floss. "He had been around for so long that people hadn’t really been thinking about 'what happens if,' and so it hit [Galapagueños] really hard." They immediately began working to preserve George’s remains as quickly as possible. “This is a large animal, and this is a tropical environment,” she says. “We really wanted to make sure that [George] was stabilized and then let the park explore the options and make the decision about what to do with him.”

So Sterling placed a call to the museum, speaking with scientists there as well as George Dante, taxidermist and founder of Wildlife Preservations. “They gave me really good, detailed advice about what we needed,” she says, “and then we went on a little bit of an adventure around the Galapagos to find those things.”

Absolutely necessary, Dante said, was thick freezer plastic. “So we went to the hardware store and said ‘Do you have any?’” Sterling recalls. “And he said ‘No, but we can order you some and it’ll come in 2 weeks from now.’” Which, obviously, wasn’t fast enough. But when Sterling and her colleagues explained that the plastic was for Lonesome George, “they called friends who called friends, and the pig farm had some, and they gave us the plastic.”

But getting the plastic was just the beginning of preparing George’s remains to be frozen. “I had to wrap each one of those toes in tissue paper because when an animal freezes, the pieces that hang out can break off—we had to tuck his head in, we had to tuck his tail in,” Sterling says. “Meat in the freezer can get freezer burn, so anything that was soft tissue—the eyes, the skin—we wrapped wet towels around, and when those dried, we wrapped him again. We basically had a lot of tissue, paper towels, whatever we could find, and then we wrapped him several times in plastic.” They also had to make sure that none of the tortoise’s bodily fluids got on the shell, which would stain it.

It was a big operation, Sterling says, but “we were trying to make sure he was in the best shape he could be for whoever ended up working on him.” And she notes that preserving George would have been difficult to do without the help of Galapagos residents. “All the different pieces came from different places, from all the people who really wanted to care for him and be a part of him,” she says.

Once George was securely wrapped, they had to find a freezer big enough to store the 5-foot-long, 165 pound tortoise, and settled on keeping George’s remains in a fishery freezer—where they remained for nine months—while the park’s scientists weighed their options. Ultimately, they chose to send him to the American Museum of Natural History, where he would be taxidermied by Dante.

Getting him to the taxidermist was no easy feat, since there are no direct flights from the Galapagos to the United States. SUNY's James Gibbs served as George’s chaperone. “What we wanted to ensure at that point was that he was stable in the airports,” Sterling says. “James was there to make sure he got [on and off] each plane, or if there was a delay that [the remains] would get frozen again in the airport—he probably had all these views of the back ends of airports that none of the rest of us get to see—and then brought him to JFK in New York City. There were a lot more logistics than one would ever think involved in trying to ensure that he arrived here safely.”

Dante called George’s long journey, which ended at the museum in April 2013, “the most miraculous part of this process, to make sure he didn’t defrost and nothing happened to the specimen.” But the most challenging part—for the taxidermist, at least—was yet to come.

Top: The beginning of Lonesome George's trip from the Galapagos to NYC. Photo by James Gibbs. Bottom: The tortoise arrives at the American Museum of Natural History. Photo by AMNH/D. Finnin.

Though every mount is different, most species have been taxidermied before, and there are best practices available. But no one had ever taxidermied C. abingdoni before. For George, there was no script. “There’s nothing written, no contemporary information for things like how long it took for his skin to dry,” Dante says. “The biggest challenge was making sure he looked like Lonesome George. My biggest fear was for the people of the Galapagos to come and say ‘That doesn’t look like George. It looks like a generic Galapagos Tortoise.’ It weighed heavy on my mind.”

Conservation and taxidermy experts unpack Lonesome George upon his arrival from the Galapagos at the American Museum of Natural History in July 2012. Photo courtesy of AMNH/D. Finnin.

Dante came to the museum to receive and check George before transporting him to Wildlife Preservations’ West Paterson, New Jersey studio, 17 miles west of NYC. There, the taxidermist and his colleagues use the Akeley Method—which was created by naturalist and AMNH taxidermist Carl Akeley “when there were no supply companies and instructions written on how to do these things; it’s a process that’s really old”—to create mounts for museums around the country as well as artists and private clients.

So they began as Akeley would have, taking photographs, drawing sketches, and making casts of the tortoise’s head and feet, “so we had some sort of reference once we started to remove the skin from him and started the traditional taxidermy process,” Dante says. They also looked at photographs and video of George while he was alive.

In the early stages of the taxidermy process, multiple casts of Lonesome George’s extremities were taken for future reference. Photo courtesy of AMNH/D. Finnin.

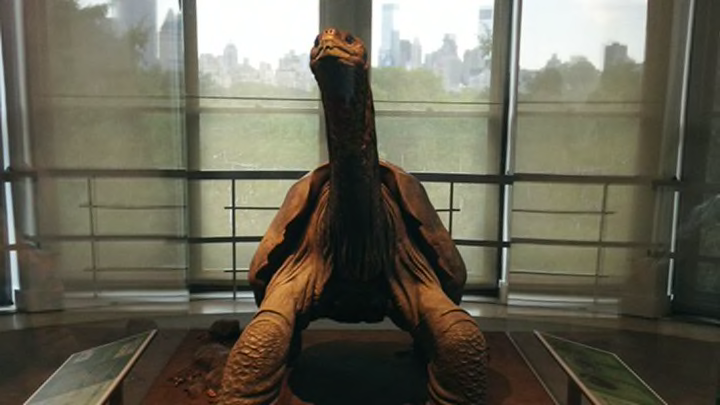

Dante and his team worked closely with Sterling, Museum Herpetology Department curator Christopher Raxworthy, and their colleagues in the Galapagos to make sure George looked just as he did in life (including the missing toenail on his left front foot). They decided to position the tortoise with his neck outstretched to show off his saddle-back shell—an adaptation that allowed him to lift his head high to get food and as a display of dominance.

Wildlife Preservations founder George Dante drew this sketch of the pose portrayed in Lonesome George’s taxidermy mount. Courtesy of AMNH/C. Chesek.

They also chose to place green stains down his throat as if he had just eaten; with natural coloration, Raxworthy said in remarks, George looked too perfect. Even nailing the eye color was a challenge—no one had captured a good photo of the iris of a giant tortoise.

Inside, George is all foam (as are most other taxidermied animals). “We did a clay structure of George’s anatomy, and then we molded and cast the clay and made a foam positive,” Dante says. “Because this is a sculpture inside of him, I needed to make sure my structure reflected the character of George.” Though he weighed 165 pounds alive, now George weighs just 50 pounds. The taxidermists saved what was left of George’s remains, which will likely be returned to the Galapagos.

Top: One of the final steps in the taxidermy process is producing a clay sculpture that defines the musculature and shape of the animal. Once it is tested and fits perfectly underneath the tanned skin, a lightweight mold is made to replace the clay armature. Photo courtesy of AMNH/D. Finnin. Bottom: Eleanor Sterling, chief conservation scientist for the Museum’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation (right) and Wildlife Preservations founder George Dante. Photo courtesy of AMNH/C. Chesek.

The taxidermy process took more than a year, and all the hard work paid off: Lonesome George looks as though he’s going to step out of his glass case in AMNH’s Astor Turret, where he’s on display until January 2015, after which he goes home to Ecuador. “We’re pretty excited he looks so gorgeous,” Sterling says. The hope, she says, is that George can continue to captivate people in death as he did in life, and spur conversations and support of conservation in the Galapagos and beyond.

Lonesome George is on view in the Museum’s 4th floor Astor Turret through January 4, 2015. Photo courtesy of AMNH/R. Mickens.