Fans of superheroes, hard-boiled detectives, and sci-fi who came of age in the 1930s through the 1970s were accustomed to asking store proprietors where they stocked their comics. And if they ran across a fellow enthusiast, they'd inevitably ask which comics they picked up every week. It wasn’t until the 1980s and the rise of prestige titles like 1986’s The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen that the phrase graphic novel entered the lexicon. Readers used it to denote their feeling that comics were more substantive than non-readers might believe; those same non-readers uttered the term with a sniff of condescension, as though comics fans were merely trying to dress up their hobby with more sophisticated language. The term was sometimes even used in quotes, as though people were not quite sure what to make of it.

So what’s the actual difference between comic books and graphic novels? Are these terms interchangeable, or does each possess identifying characteristics?

Comic books are, of course, recognizable as periodicals issued on a regular basis that feature sequential artwork. The earliest examples of American comics date back to the 1920s, when newspaper strips like Mutt and Jeff and Joe Palooka were collected and reprinted. By the 1930s, comics started to feature original material, and soon became the medium of choice for the burgeoning superhero genre and resembling the issues we see on shelves today.

In 1964, a comics fan named Richard Kyle used the terms graphic story and graphic novel in an article about the future of the comics medium for a fanzine, or self-published fan magazine. Kyle and another fan, Bill Spicer, later issued a fanzine titled Graphic Story Magazine in what was likely an attempt to modernize the medium and perhaps afford it a higher level of credibility. That may have been made more difficult by the 1966 television debut of ABC’s Batman, which embraced the DC character’s kitschy aspects and rendered comics as perceived juvenilia for decades to come.

The term graphic novel was used only sporadically through the 1970s and early 1980s. In 1971, DC Comics declared The Sinister House of Secret Love #2 and its 39-page story a "graphic novel of gothic terror” on the issue’s cover. In 1976, artist Richard Corben’s Bloodstar, a 104-page fantasy comic based on the work of Conan creator Robert E. Howard, declared itself a graphic novel on the book’s flap. So did A Contract with God, a 1978 work by comics legend Will Eisner. There was a clear association being made between length and terminology, with longer works increasingly being labeled graphic novels.

In the early 1980s, Marvel began releasing a line of graphic novels like The Death of Captain Marvel that were larger than the average comic, with a heftier price tag of $4.95. The titles were representative of the increasing trend toward comics wrapped in more elaborate packaging. In a 1983 profile of Atlanta artist Rod Whigham and his 111-page work, Lightrunner, the term graphic novel was presciently described by Science Fiction and Mystery Bookstore owner Mark Stevens: "A graphic novel is like a comic book but much longer," he said. "The format is larger, usually bound and the story has a definite ending.”

The term was also embraced by Mort Walker, the creator of the comic strip Beetle Bailey, who published two graphic novels featuring the beleaguered Army soldier in 1984. The books, Friends and Too Many Sergeants, were all-new sequential art stories, not reprints of the strip. Walker cited European graphic novels as inspiration, saying that comics readers overseas suffered less of a stigma than domestic readers. "Businessmen, for instance, commuters going to work, are not embarrassed to read graphic novels on the train,” he said.

Because of the history of graphic novels having more reputed substance than single-issue comics, the phrase took off in the 1980s, when DC published trade paperback collections of Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. Alan Moore, the writer of Watchmen, later observed that graphic novel caught on with marketing departments. "You could just about call Maus a novel, you could just about call Watchmen a novel, in terms of density, structure, size, scale, seriousness of theme, stuff like that,” he said. "The problem is that 'graphic novel' just came to mean ‘expensive comic book’ and so what you’d get is people like DC Comics or Marvel Comics, because graphic novels were getting some attention, they’d stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel, you know?”

This protracted history is where we likely find the true separation between comics and graphic novels. By and large, comic books are periodicals. They are published regularly and in an economical format, pages stapled together. Often, a comic book cannot stand on its own as a complete narrative. It builds off what has come in issues before it.

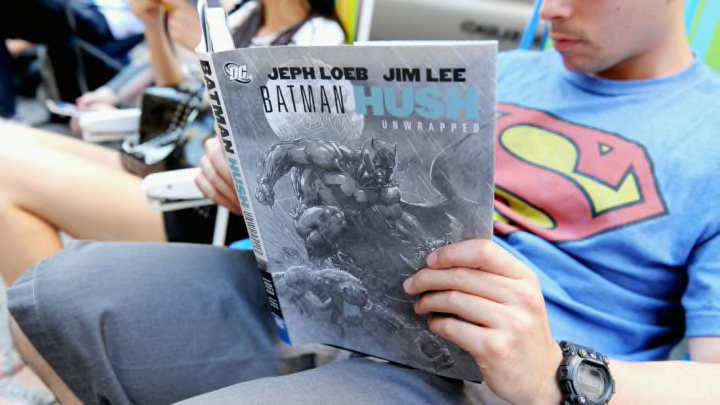

A graphic novel, on the other hand, tends to be considerably longer than an average comic’s 22 pages and tells a largely self-contained story. According to Bone creator Jeff Smith, the graphic novel has a beginning, middle, and end, with little of the ephemeral quality of a comic and its static characters. The packaging is typically more robust, with actual binding and better paper or color reproduction quality. By virtue of the fact it’s collecting an ongoing narrative from a comics series—both Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns were first sold as individual issues—or telling an original story, it offers some finality. And while people may expect more substantial thematic or narrative exploration than they would in a comic, it could still conceivably be, as Moore asserts, a worthless piece of crap.

Owing to this subjectivity, it’s hard to say The Dark Knight Returns is not a comic book, although it might be a stretch to call a single issue of Howard the Duck a graphic novel. That term might be best reserved for titles that provide a richer storytelling experience with a definitive conclusion. Or we could agree with Moore, who considers the difference minimal. "The term ‘comic’ does just as well for me,” he said.

If you're on the hunt for comic book gift ideas, you may also want to take a look at our gift guide.

Have you got a Big Question you'd like us to answer? If so, send it to bigquestions@mentalfloss.com.

A version of this article was originally published in 2019 and has been updated for 2022.