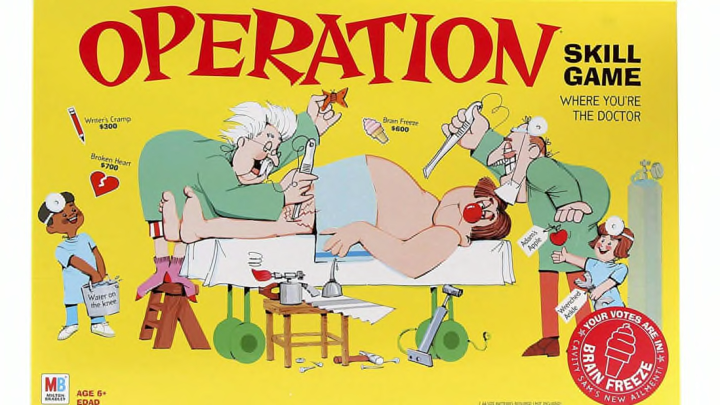

For more than 50 years, players have had fun practicing medicine without a license in Operation. The popular tabletop game tasks amateur surgeons with extracting game pieces—foreign objects and body parts—using tweezers without slipping and activating a buzzer that lights up the patient’s nose. (This procedure, which looks to deprive the man of all his important innards, is seemingly performed without anesthesia.) Check out some facts on the game’s history, including its more recent ailments and how it inspired a real-life operation.

1. Operation started as a college project.

John Spinello was an industrial design student at the University of Illinois in the early 1960s. In class one day, he was instructed by his professor to design a game or toy. Remembering an ill-advised moment when he had stuck his finger into a light socket as a child, Spinello came up with a box that had a mild electrical current created by one positive and one negative plate a quarter-inch apart. When players tried to guide a probe through the box’s grooves, they had to be careful not to touch the sides. If they did, the probe would complete the circuit and they’d activate a buzzer.

The game was a hit with Spinello’s fellow students, and Spinello decided to show it to his godfather, Sam Cottone, who worked at a toy design firm named Marvin Glass and Associates. Marvin Glass loved the game and paid Spinello $500 (the equivalent of a little more than $4000 today) for the rights, as well as a promise of a job upon his graduation in 1965. Spinello got the money but no job—not right away, anyway. He finally joined at the company in 1976.

2. Operation was originally named Death Valley.

Spinello had created an intriguing idea for a buzzer-based game, but initially, there was no clear premise. Cottone suggested the box and probe take on a desert theme, where players would extract water from holes in the ground. The working title was Death Valley. When Milton Bradley bought the game rights from Marvin Glass and Associates, one of their designers, Jim O’Connor, suggested they switch from a probe to a pair of tweezers in order to actually extract small items from the holes. The setting was changed from a desert to an operating theater, and Operation was released in 1965.

3. Cavity Sam got a new diagnosis in 2004.

For decades, the various ailments of Cavity Sam—a funny bone, a broken heart, etc.—remained unchanged. In 2004, Hasbro introduced the first addition to his laundry list of complaints with a diagnosis of Brain Freeze, represented by an ice cream cone waiting for extraction from his head. Fans of the game were able to vote online for Sam's first new ailment: Brain Freeze beat out Growling Stomach and Tennis Elbow with 54 percent of the vote. Later versions have added Burp Bubbles and flatulent sound effects for an ailment dubbed Toxic Gas. Hasbro has also offered licensed versions of the game, including boards based on the Toy Story and Shrek franchises.

4. The inventor of Operation didn’t make any money off Operation.

In 2014, word circulated that Spinello was in need of oral surgery that would cost around $25,000. Because he had sold the rights to Operation for just $500, he had not received any royalties from sales of the game. Fortunately, a round of crowdfunding allowed him to get the procedure he needed. Hasbro, which bought Milton Bradley, also donated to the effort by buying Spinello’s original prototype.

5. Operation inspired a real-life operation that has helped thousands of people.

Surgeon Andrew Goldstone was a fan of Operation as a child. When he got older, he took the game’s premise to heart. Goldstone noticed that thyroid surgeries were risky due to the thyroid’s proximity to the nerves of the vocal cords. A small slip could damage the cords, causing hoarseness or airway obstruction. Goldstone thought surgeons should have a buzzer similar to the one in the game that alerted them when they got too close. He applied an electrode to the airway tube used during general anesthesia. If a surgeon touched the nerves of the vocal cords with a probe, a signal would pass to the electrode and a buzzer would sound. Goldstone sold the technology back in 1991. It’s been used in thousands of thyroid surgeries since. Unfortunately, the patient’s nose does not light up.