Introduced in the United States in 1949, the board game Clue has gone on to become a perennial item in millions of closets all over the world. In this morbid murder mystery, players must move from room to room in a mansion to determine who did away with the victim—the unfortunately named Mr. Boddy—as well as the method and location of the crime. Was it Colonel Mustard in the library or Miss Scarlett in the kitchen? Was it a candlestick or a revolver? For more on the history of this detective diversion, keep reading.

1. Clue was invented during the UK air raids of World War II.

In the early 1940s, a British musician, fire warden, and munitions factory worker named Anthony Pratt was holed up in his Birmingham home during air raids. During these nights, he recalled the murder mystery games played by some of his clients at private music gigs as well as the detective fiction popular at the time from authors like Raymond Chandler and Agatha Christie. Slowly, Pratt and his wife, Elva, turned the idea into a board game they could play while waiting out the raids. Pratt filed a patent for the game in 1944, which was granted in 1947; Pratt then sold it to UK games manufacturer Waddington’s. Owing to war shortages, it wasn’t actually released there until 1948.

2. Clue wasn’t always called Clue.

When Pratt sold his game to Waddington’s, he named it Cluedo, a blend of clue and Ludo, the name of a 19th century board game that’s Latin for “I play.” When Parker Brothers picked up the rights to the game in America in 1949, they shortened it to Clue since Americans had no knowledge of the Ludo game.

3. Early versions of Clue featured different weapons.

Pratt’s earliest ideas for murder implements were sketched by Elva and were originally a bit more gruesome. In his patent application, Pratt listed an ax, a cudgel (stick), a small bomb, rope, a dagger, a revolver, a hypodermic needle, poison, and a fireplace poker. The rope, gun, and dagger made it to the final game, along with three new weapons: a candlestick, a wrench, and a lead pipe.

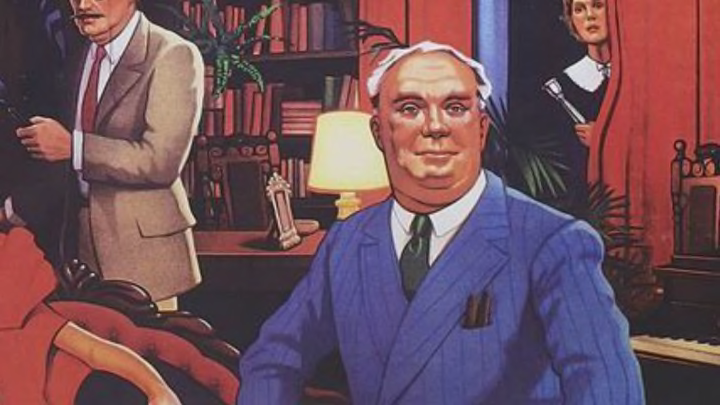

4. Clue's Colonel Mustard was originally Colonel Yellow.

Pratt detailed 10 characters in total in his patent application: Doctor Black, Mr. Brown, Mr. Gold, the Reverend Mister Green, Miss Grey, Professor Plum, Miss Scarlett, Nurse White, Mrs. Silver, and Colonel Yellow. Not all the characters survived the process of simplifying the gameplay and were eventually whittled down to six. Colonel Yellow remained but got a name change to Colonel Mustard. Norman Watson, an executive director at Waddington’s, was wary of using the word yellow because it was military slang for cowardly, which made little sense for an enlisted man. (Watson, incidentally, had experience in cunning and clever gamesmanship, though it wasn’t relegated to a table. At the behest of Mi9, he had slipped escape tools and maps into board game packages that were delivered to British prisoner-of-war camps.)

5. There’s a Clue world champion.

In 1993, Peter DePietro and Tom Chiodo of the Manhattan Rep Company promoted a Clue world championship event in New York City. Part competition and part performance art, contestants played while interacting with actors dressed as Clue characters. Clues were doled out in dialogue and via music. The winner was Josef Kollar from the UK, who also came dressed as Colonel Mustard. Kollar won a trip to Hollywood.

6. Cluedo was a hit British game show.

In 1990, Cluedo was adapted into a game show in which two teams of celebrities would watch as guest performers—including David McCallum (The Man from U.N.C.L.E.), Tom Baker (Doctor Who), and Joanna Lumley (Absolutely Fabulous)—related clues in character. The show ran for four seasons.

7. There was a Clue musical.

You may recall the 1985 feature film Clue, which featured Tim Curry and others assuming the roles of the board game characters. But there’s also a stage version. Clue: The Musical opened in Baltimore in 1995 and fleshed out some of the tortured relationships of the ensemble that lead to the nightly murder of Mr. Boddy. Audience members were invited to pick three oversize cards that would identify the murderer, weapon, and location. Clue world champion promoter DePietro wrote the book; Chiodo wrote the lyrics; Wayne Barker, Galen Blum, and Vinnie Martucci composed the music. The musical went on to be performed in more than 500 cities around the world.

8. Clue got a makeover in 2008.

Doing away with the elegant aesthetic of the original, Hasbro (which owns Parker Brothers) decided to revise the game in 2008 to reflect more contemporary themes. The murder takes place at a celebrity party, with rooms including a spa and a theater; characters got revised backgrounds. Colonel Mustard morphed from a military man to a football hero; Professor Plum became a dot-com billionaire. Some weapons disappeared, while three new weapons were added: a trophy, ax, and baseball bat. The "retro" original is still available.

9. Clue killed off Mrs. White.

No one ever stays dead for long in Clue—unless you’re Mrs. White. In 2016, Hasbro decided to off the murderous housekeeper in favor of a new character, Doctor Orchid, a scientist who isn’t above bludgeoning someone with a candlestick. It was the first time a character in the game had ever been permanently retired.

10. The creator of Clue didn’t profit all that much from it.

In the late 1990s, Waddington’s sent out a press release soliciting information about Pratt. After selling 150 million Clue games, they wanted to see if they could locate its creator. Pratt had largely fallen out of sight since the 1960s, when his patent on the game lapsed and he stopped receiving royalty payments. He received no royalties on U.S. or international versions of the game, choosing instead to sign over those rights in 1953 for 5000 pounds (then about $14,000). He was unaware that the game was already a hit in the States.

Pratt tried to create two other games—one revolving around a buried treasure and the other about a gold mine—but was unsuccessful. In 1990, he gave an interview in which he expressed no bitterness over missing out on a fortune. “A great deal of fun went into it,” he said. “So why grumble?” He died four years later at the age of 94.