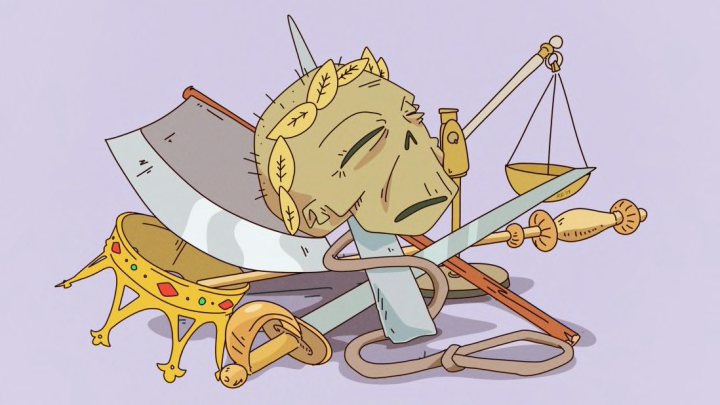

After Oliver Cromwell died of “a bastard tertian ague” on September 3, 1658, his funeral proceedings had all of the pomp and circumstance typically shown for the passing of a king. Cromwell, of course, was not a king—he was the Lord Protector of England, Ireland, and Scotland, the man who had abolished the monarchy after ordering the beheading of Charles I, and who had refused the crown during his lifetime.

Cromwell likely would have hated all the fuss, which cost an estimated 60,000 pounds. But no matter—he was dead. And after his embalmed body, encased in a coffin topped by a lifelike effigy, laid in state for two months, he was interred like a king, too, in a vault in Westminster Abbey, the final resting place of monarchs Henrys III, V, and VII; Edwards I, III, V, and VI; Mary, Queen of Scots; and Queen Elizabeth I, among others.

But Cromwell wouldn’t rest in peace for long. In January 1661, a group loyal to the restored Royalists—who had overthrown Cromwell’s son, Richard, in 1659—dug up his body, dragging it from Westminster Hall to a pub and then through the streets to the gallows at Tyburn. There, on the 12th anniversary of the beheading of Charles I, they gave Cromwell's corpse (and the bodies of two co-conspirators who'd had a hand in the beheading) a posthumous execution by hanging.

Cromwell’s body was on display “from the morning till four in the afternoon,” according to an eyewitness; then, the body was cut down and the head severed (in eight cuts, which knocked out teeth and messed up the nose). It was shoved on a 20-foot-tall wood pole affixed with a metal spike and placed at Westminster Hall for all to see. “[Cromwell’s] severed head was as hollow and dead as his republican ideals,” Frances Larson writes in Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found, “and as long as it played its part as the marionette on the roof of Westminster Hall, no one would be allowed to forget.”

In death, Cromwell had experienced many indignities. But this was not the end. No, the strange saga of Oliver Cromwell’s head had only just begun.

From Palace-Side Attraction to Museum Exhibit

From its perch on the south side of Westminster Hall, Cromwell’s head served as a warning—and a morbid tourist attraction—for more than 30 years. (It was briefly removed in 1681 for some roof work.) As Jonathan Fitzgibbons writes in his book Cromwell’s Head, “Anecdotal evidence claims that the head finally came down one evening in the midst of a great storm that battered London towards the end of the reign of James II.” The oak pole holding the head snapped, depositing it at the feet of a guard, who supposedly picked it up, took it home, and stashed it in his chimney. According to an account written in 1727, the guard, “Having concealed it for two or three days before he saw the placards which ordered any one possessing it to take it to a certain office ... was afraid to divulge the secret.” Despite the fact that a substantial reward was offered for the return of the head, the guard feared punishment, and he kept his secret until his dying day (sometime around 1700), when he finally revealed the location of the head to his daughter.

His daughter, in turn, supposedly sold it. After its disappearance from Westminster, Cromwell’s head didn’t officially resurface until 1710, when it popped up in a London museum belonging to Claudius Du Puy. The head fit right in at the four-room museum, whose cabinets, according to Fitzgibbons, “were crammed full of strange items intended to attract the visitor’s baffled queries and amazement.” Cromwell’s head was located in the second room, and Du Puy called it “one of the most curious items” in his establishment. One visitor called it “this monstrous head.”

After Du Puy’s death in 1738, the head vanished again—and this time, its location would remain a mystery for 40 years.

A Drunkard’s Prized Possession

James Cox was near the London neighborhood of Clare Market when he saw a curiosity that he simply had to have.

It was around 1780 when Cox—who had at one point owned a museum—spotted Cromwell’s head being exhibited in a stall. It was being shown by Samuel Russell, whom Fitzgibbons describes as a “failed comic actor” and an alcoholic who claimed to be a descendent of Cromwell; the head, Russell claimed, had come down to him through generations of his family. (“Perhaps there is some truth in this,” Fitzgibbons writes. “The Cromwell and Russell families were connected through a number of marriage alliances … perhaps Oliver’s relatives were seen as a ready market for such a strange item following Du Puy’s death.”)

Cox offered Russell 100 pounds for the head, but Russell refused. So Cox decided to get the head through other means.

According to the pamphlet Narrative Relating to the Real Embalmed Head of Oliver Cromwell, Russell was “in indigent circumstances” and asked Cox for financial help, which Cox gave, “partly from humanity, and partly (he confesses) with a view to the acquisition, sometime or other, of so great a curiosity.” He patiently lent Russell money until, in 1787, he asked for repayment of the 118 pounds he’d given. Russell had nothing to give … except for Cromwell’s head. He reluctantly transferred ownership to Cox.

Cox then began talking up his unusual acquisition with the goal of driving up its price, spreading word far and wide but only letting a select few actually see it. In 1799, he sold the head for 230 pounds—at nearly twice what he paid, a tidy profit—to the Hughes brothers, who planned to exhibit it in their own museum on Bond Street in London. (The Narrative pamphlet was created for that museum.) But the museum failed; after it closed, all three Hughes brothers quickly died, leading to rumors of a curse.

A Subject of Scientific Scrutiny

But no curse could relegate Cromwell’s head to obscurity. A daughter of one of the Hughes brothers began exhibiting the noggin again in 1813—and she was eager for someone to take it off her hands. Piccadilly Museum considered purchasing it, but opted not to because, as Robert Jenkinson, the 2nd Lord Liverpool and Prime Minister, noted, of “the strong objection which would naturally arise to the exhibition of any human remains at a Public Museum frequented by Persons of both Sexes and of all ages.”

Two years later, the daughter found a buyer at last: Josiah Henry Wilkinson. The Kent resident delighted in his curio, placing it in a small oak box and bringing it out at gatherings. “A frightful skull it is,” a woman who saw it in 1822 later wrote, “covered with its parched yellow skin like any other mummy and with its chestnut hair, eyebrows and beard in glorious preservation—The head is still fastened to the inestimable broken bit of the original pole—all black and happily worm eaten." Wilkinson noted that "The nose is flattened as it should be when the body was laid on its face to have the head chopped off … There is the mark of a famous wart of Oliver’s just above the left eye brow on the skull.” The head remained in the Wilkinson family, passing down from generation to generation.

But by the 19th century, the Wilkinson head wasn’t the only noggin purported to be the Lord Protector’s floating around—in fact, there were several others. In 1875, one such skull at Oxford's Ashmolean Museum went head-to-head with Wilkinson’s, which by then belonged to Josiah’s grandson, Horace. George Rolleston, professor of anatomy and physiology at Oxford University, declared Wilkinson’s head the real deal. The Wilkinson head was subjected to more scientific scrutiny in 1911, this time by scientists at the Royal Archeological Institute, which according to Fitzgibbons came to the conclusion that “while the documentary evidence was slightly dubious, the physical evidence was extremely strong. Although it was not categorically proved that this was Cromwell’s head … there was no way the possibility could be refuted.”

So even though the Wilkinsons were convinced that the head in their possession had belonged to Cromwell, doubt still lingered. And so, in 1934, Canon Horace Wilkinson agreed to let scientists Karl Pearson and Geoffrey Morant take the head and publish the results of their assessment in the journal Biometrika.

Rather than get hung up on where the head had come from, Pearson and Morant chose to focus on the head’s physical appearance: How close a match was it to Cromwell? Did the details of the head match up with its supposed history?

The embalming certainly lined up with what would have been done at the time of Cromwell’s death. Cromwell's skullcap had been removed—this was "usual in all major and particularly in royal embalmments"—and sewn back on. The head was still attached to its pole, which, they wrote, “had long been in contact with the Head, for some of the worm holes pass through the Head and the pole.” The spike that had been thrust through the top of the head was gone—rusted away—but using X-rays, the scientists were able to see that it was still intact in what they called the brain-box. “This prong has been so forcibly thrust through the skull-cap that it has split it from the place of penetration to the right border,” they wrote.

Next, according to Fitzgibbons, they used busts, life masks, and death masks of the late Lord Protector to take measurements, which they then compared to the head. Despite the fact that some shrinkage of the skin made the comparison complicated, Pearson and Morant came away with the conclusion that “the accordance between the mean of the masks and busts and the Wilkinson Head is astonishing.” The measurements were, Fitzgibbons writes, “almost an exact match”—right down to the wart above Cromwell’s eye.

At Rest, At Last

In 1960, the long journey of Oliver Cromwell’s head finally came to an end. Three years earlier, after Canon Horace Wilkinson’s death, his son, Dr. Horace Norman Stanley Wilkinson, took possession of the relic—and he decided it was time to lay it to rest once and for all. He coordinated with Sidney Sussex College, a college of Cambridge University that Cromwell had attended, to find a final resting place.

Cromwell’s first funeral had been attended by thousands; the interment ceremony for what was left of him, on March 25, 1960, was much smaller. Just seven people were present as the head, in its oak box and sealed in an airtight metal container, was buried somewhere near the the college's antechapel. Two years later, a plaque was erected to announce its burial. But just as was true of the head for much of its history, its exact location is unknown to all but a few.