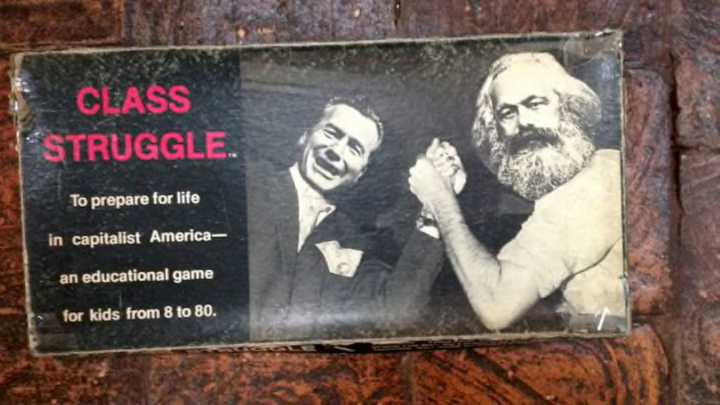

The box for the Class Struggle board game features Karl Marx arm-wrestling Nelson Rockefeller. They’re using their left arms, so of course Marx is winning. Inside the box, a pile of Chance Cards includes messages such as “You are treating your class allies very badly” and “Your son has become a follower of Reverend Moon.” The ultimate goal of the game is to avoid nuclear war and win the revolution.

When the game was released in 1978, the U.S.A. and U.S.S.R. were locked in the Cold War and the specter of communism was still scary to the average American. Even then, Class Struggle sold around 230,000 copies. Before it went out of print, it was translated into Italian, German, French and Spanish.

Just how did this game become so popular? The story begins with a quirky Marxist professor trying to change jobs and ends with him getting sucked into the very system he was trying to subvert.

Professor Bertell Ollman had been teaching at New York University for a decade when he was offered the opportunity to chair the University of Maryland’s political science department, pending approval from the provost. The possibility of a noted Marxist scholar heading up a university department was not one to be ignored by the D.C. press, and they hopped on the story with a quickness today’s political bloggers would appreciate. Maryland’s governor and state senators started weighing in, and the approval process slowed way, way down.

Around the same time, Ollman was researching board games, in search of a socialist alternative to Monopoly. As he discusses in his 1983 memoir, Class Struggle Is the Name of the Game, Ollman learned Monopoly was actually based on The Landlord Game, which was invented in 1903 by a Quaker named Elizabeth Magie.

The original version had a different message, however, and as late as 1925 the game included the following instructions: “Monopoly is designed to show the evil resulting from the institution of private property. At the start of the game, every player is provided with the same chance of success as every other player. The game ends with one person in possession of all the money.”

Of course the Parker Brothers version that inflames family arguments today has flipped the script, which left Ollman pondering just how he could make a game that gives players equal chances yet still teaches them about the inequalities of capitalism. Then came his breakthrough. “What if the players are not individuals, but classes?” he writes. “One could make capitalists and workers roughly equal in power, though of course the sources of their power are very different. The game could even explore these different sources of power, and when and how they are used. The game could deal with the class struggle.”

Ollman had his game, whose rules involve two to six players taking on the roles of capitalists, workers, farmers, small businesspeople, professionals, and students. They move around the board while dealing with elections, strikes, wars, and whatever the Chance Cards throw their way, including, “Yesterday you shook hands with Republicrat Senator Kennewater, and you believed him when he said he is the workingman’s candidate. Lose 1 asset for being so gullible.”

What Ollman didn’t have was any practical knowledge of small business, and the first run of the game was destined for dusty storage until a New York Post article picked up the story and attached it to the University of Maryland controversy. Articles soon followed in the Chicago Sun-Times, The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Baltimore Sun. The Village Voice called the game a “shade prim” for saying marijuana and alcohol were opiates of the people.

The game was a hit, and Class Struggle started appearing on shelves alongside Monopoly. But Ollman soon learned getting orders was not the same thing as getting paid, and the Marxist scholar quickly became an expert in how small businesspeople get squeezed. Many radical bookstores never paid him for the games, and relations became strained with his initial investors, who also happened to be his good friends. Bad publicity followed when a small group of striking workers at Brentano’s Bookstore asked him to pull the game and then used his refusal to promote their own fight.

“Even my political commitment was beginning to fray at the edges,” he writes in his memoir. “I had always been delighted by each downturn of sales reported in the marketplace — ‘People buying less junk,’ I thought. Now, the same news appeared somehow threatening. I caught myself thinking, ‘If the collapse of capitalism could wait just a little longer, until we got our business on its feet.’”

Success was always right around the corner, but the costs kept rising. When Ollman and his cohorts did not have enough money for the second run of the game, they seized upon a small difference in quality to refuse payment to the manufacturer. Lawsuits ensued. (A word of advice: Never go into business with a Marxist.) The University of Maryland’s provost punted the decision about the political science department to his successor, who denied Ollman’s appointment. More lawsuits. Ollman’s game was still selling, but the enterprise was sinking further into debt.

“Being broke is bad enough,” he writes. “Being broke and mistaken for a millionaire—by everyone but the bank, that is—is about as funny as coughing up blood.”

Ollman was grinding his teeth so badly that four of them cracked, and after three years of struggle, the professor and his partners sold the game to Avalon Hill, a company that specialized in war games. The game disappeared in 1994.

As for Ollman, he is still a professor at New York University, and when asked about the game’s legacy, he tells Mental Floss:

“As long as there is a class struggle (and there certainly is in the U.S., where it may have gotten more intense, especially during the current economic crisis), there is a great need to help young people understand what it is, how it works, and where they fit into it. They are certainly not going to learn any of this from the mainstream media or in most of their formal education. The game could still contribute to this important work.”

Just watch out for Republicrat Senator Kennewater.

All photos by Keith Ploceck