It's easy to forget that before the dawn of film, stage actors were power players; many of them carried just as much clout as modern Hollywood stars. In 1880, Sarah Bernhardt earned $46,000 for a month of performances on her first New York tour alone (which would be well over $1 million today). In 1895, English actor Henry Irving made enough of a name for himself to become the first actor in history to receive a British knighthood. And way back in 1849, two rival Shakespearean actors, William Macready and Edwin Forrest, caused such a stir with their competing productions of Macbeth that their fans ended up rioting in the streets of Manhattan.

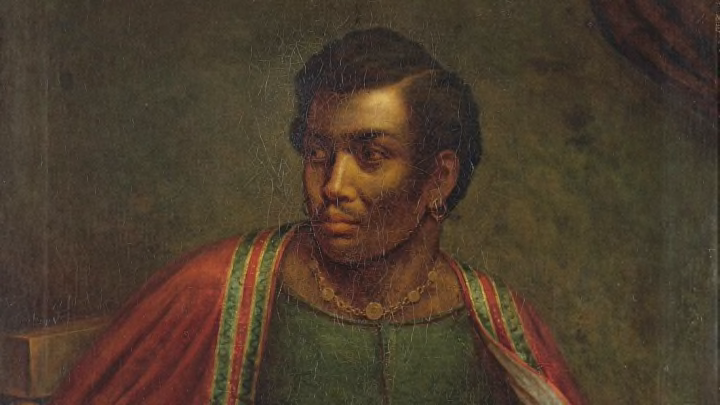

But before all of them, there was Ira Aldridge. Born in New York in 1807, Aldridge made such a name for himself in the theaters of the mid-19th century that he went on to be awarded high cultural honors, and is today one of just 33 people honored with a bronze plaque on a chair at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. But what makes Aldridge’s achievements all the more extraordinary is that, at a time of widespread intolerance and racial discrimination in the U.S., he was black.

Young, Gifted, and Black

The son of a minister and his wife, Aldridge attended New York’s African Free School, which had been established by the New York Manumission Society to educate the city's black community. His first taste of the theater was probably at Manhattan’s now-defunct Park Theatre, and before long he was hooked. While still a student, Aldridge made his stage debut—at the African Grove Theatre, which had been established by free black New Yorkers around 1821—in a performance of Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s adaptation of Pizarro. According to some accounts, his Shakespearean debut followed not long after, when he took on the title role in the African Grove Theatre's production of Romeo & Juliet.

These early performances were successes, as was the African Grove Theatre, which quickly proved the most renowned of the few theaters in New York staffed mainly by black actors and attended mostly by black audiences. But despite these early triumphs, both Aldridge and the Grove had their fair share of hardships.

Shortly after its opening, the Grove was forced to close by city officials, supposedly over noise complaints. The project was relocated to Bleecker Street, but this move took the theater away from its core black audience in central Manhattan and planted it closer to several larger, more upmarket theaters, with which it now had to compete. Smaller audiences, coupled with resentment and competition from its predominantly white-attended neighbors, soon led to financial difficulties. And all of these problems were compounded by near-constant harassment from the police, city officials, and intolerant local residents.

Eventually, the situation proved unsustainable: The Grove closed just two years later (and was reportedly burned to the ground in mysterious circumstances in 1826). As for Aldridge, having both witnessed and endured racist abuse and discrimination in America, he decided he'd had enough. In 1824, he left the U.S. for England.

The African Tragedian

By this time, the British Empire had already abolished its slave trade, and an emancipation movement was growing. Aldridge realized that Britain was a much more welcoming prospect for a young, determined black actor like himself—but what he didn’t know was that his transatlantic crossing would prove just as important as his decision to emigrate.

To cover the costs of his travel, Aldridge worked as a steward aboard the ship that took him to Britain, but during the journey he made the acquaintance of British actor and producer James Wallack. The pair had met months earlier in New York, and when they happened to meet again en route to Europe, Wallack offered Aldridge the opportunity to become his personal attendant. On their arrival in Liverpool, Aldridge quit his stewardship, entered into Wallack’s employ, and through him began to cultivate numerous useful contacts in the world of theater. In May 1825 Aldridge made his London debut, becoming the first black actor in Britain ever to play Othello

The critics—although somewhat unsure how to take a "gentleman of colour lately arrived from America"—were won over by Aldridge’s debut performance in a production of Othello at the Royalty Theatre. They praised his "fine natural feeling" and remarked that "his death was certainly one of the finest physical representations of bodily anguish we ever witnessed." Astonishingly, Aldridge was still just 17 years old.

From his London debut at the Royalty, Aldridge slowly worked his way up the city’s playbill, playing ever-more-upmarket theaters across London. His Othello transferred to the Royal Coburg Theatre later in 1825. A lead role in a stage adaptation of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko followed, as did an acclaimed supporting turn in Titus Andronicus. To prove his versatility, he took on a well-received comedic role as a bumbling butler in an 18th-century comedy, The Padlock. Aldridge’s reputation grew steadily, and before long he was receiving top billing as the “African Roscius” (a reference to the famed Ancient Roman actor Quintus Roscius Gallus) or the renowned “African Tragedian”—the first African-American actor to establish himself outside of America.

Even in the more-accepting society of abolitionist Britain, however, Aldridge still had mountains to climb. When his portrayal of Othello later moved to Covent Garden in 1833, some reviewers thought a black actor treading the boards on one of London’s most hallowed stages was simply a step too far. The critics soured, their reviews became more scathing—and the racism behind them became ever more apparent.

Campaigns were launched to have Aldridge removed from the London stage, with the local Figaro newspaper among his vilest opponents. Shortly after his Covent Garden debut, the paper openly campaigned to cause “such a chastisement as must drive [Aldridge] from the stage … and force him to find [work] in the capacity of footman or street-sweeper, that level for which his colour appears to have rendered him peculiarly qualified.” Fortunately, they weren’t successful—but the affair temporarily ruined the London stage for Aldridge.

"The Greatest of All Actors"

Instead of accepting defeat, Aldridge took both Othello and The Padlock on a tour of Britain’s provincial theaters. The move proved to be an immense success.

During his national tour, Aldridge amassed a great many new fans, and even became manager of the Coventry Theatre in 1828, making him the first black manager of a British theater. He also earned a name for himself by passing the time between performances lecturing on the evils of slavery, and lending his increasingly weighty support to the abolitionist movement.

Next, he took his tour to Ireland, and on his arrival in Dublin became a near-instant star. With the island still locked in a tense relationship with Britain at the time, he was welcomed with open arms when Irish theatergoers heard how badly he had been treated in London. (In one flattering address in Dublin, Aldridge told the audience: “Here the sable African was free / From every bond, save those which kindness threw / Around his heart, and bound it fast to you.”)

By the 1830s, Aldridge was touring Britain and Ireland with a one-man show of his own design, mixing impeccable dramatic monologues and Shakespearean recitals with songs, tales from his life, and lectures on abolitionism. As an antidote to the blackface minstrel shows that were popular at the time, he also began donning “whiteface” to portray roles as diverse as Shylock, Macbeth, Richard III, and King Lear. When the notorious Thomas Rice arrived in England with his racist “Jump Jim Crow” minstrel routine, Aldridge skillfully and bravely weaved one of Rice’s own skits into his show: By parodying the parody, he robbed Rice’s performance of its crass impact—while simultaneously showing himself to be an expert performer in the process.

Such was his popularity that Aldridge could easily have seen out his days in England, playing to packed theaters every night for the rest of career. But by the 1850s, word of his skill as an actor had spread far. Never one to shy away from a challenge, in 1852 he assembled a troupe of actors and headed out on a tour of the continent.

Within a matter of months, Aldridge had become perhaps the most lauded actor in all Europe. Critics raved about his performances, with one German writer even suggesting that he may well be “the greatest of all actors.” A Polish reviewer noted, "Though the majority of spectators did not speak English, they did, however, understand the feelings portrayed on the artist's face, eyes, lips, in the tones of his voice, in the entire body." Celebrity fans were quick to assemble, including the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, and the renowned French poet Théophile Gautier, who was impressed by Aldridge's portrayal of King Lear in Paris. Royalty soon followed, with Friedrich-Wilhelm IV, the King of Prussia, awarding Aldridge the Prussian Gold Medal for Art and Science. In Saxe-Meiningen (now a part of Germany), he was given the title of Chevalier Baron of Saxony in 1858.

Aldridge continued his European tours for another decade, using the money he earned to buy two properties in London (including one, suitably enough, on Hamlet Road). But by then, the Civil War was over and America beckoned. Now in his late fifties—but no less eager for a challenge—Aldridge planned one last venture: a 100-date tour of the post-emancipation United States. Contracts and venues were hammered out, and the buzz for Aldridge’s eagerly-awaited homecoming tour began to circulate.

Alas, it was not meant to be. Just weeks before his planned departure, Aldridge fell ill with a lung condition while on tour in Poland. He died in Łódź in 1867, at the age of 60, and was buried in the city’s Evangelical Cemetery.

After his death, several theaters and troupes of black actors—including Philadelphia's famed Ira Aldridge Troupe—were established in Aldridge’s name, and countless black playwrights, performers, and directors since have long considered him an influence on their work and writing.

In August 2017, on the 150th anniversary of Aldridge's death, Coventry, England unveiled a blue heritage plaque in the heart of the city, commemorating Aldridge's theater there. Even this long after his death, the extraordinary life of Ira Aldridge has yet to be forgotten.