In the 1950s, the Kingdom of Bhutan asked the World Bank for a $10 million loan. The secluded Buddhist country with a population of about 200,000 people had been closed off to the outside world for centuries, but the government of the "Forbidden Kingdom" was now contemplating reaching out—and it needed some financial help. However, the World Bank declined to be the one to give it to them.

Bhutan, which is sandwiched between India and China, was mired in a border dispute with its giant neighbors, and the bank didn’t want to get tangled up in the politics of it all. Instead, an official suggested that Bhutan bring in money another way: by selling postage stamps to international collectors.

This idea wasn't as harebrained as it sounds. The tiny, independent city-state of Monaco, located on the French Riviera, had done the same thing several years earlier. (After discovering that stamps could be a consistent source of revenue, Monaco’s Prince Rainier III called them “the best ambassador of a country.”) So in 1962, Bhutan followed suit and set up the Bhutan Stamp Agency and placed an American entrepreneur named Burt Kerr Todd in charge.

Todd was an unusual, but ideal, choice. A swashbuckling raconteur and adventurer, he had befriended Bhutan’s future queen, Ashi Kesang Choden-Dorfi, while attending Oxford University. He was the first American to ever step foot in Bhutan and, as the son of a Pittsburgh steel and banking magnate, Todd had the worldly connections to bring global attention to the secluded nation. He was also a remarkable salesman. He was friends with dozens of heads of states, from the Sultan of Brunei to the prime minister of Mauritius, and helped dozens of small nations with wacky, money-making schemes (like the time he introduced rum production to Fiji or helped cash-strapped maharajas sell their gently used Rolls-Royces on the international market).

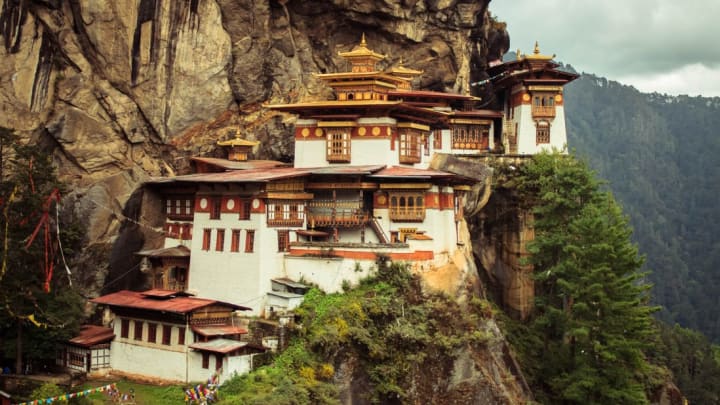

Todd’s zest for innovative ideas made him the perfect choice to lead Bhutan’s new stamp agency. He didn’t know a single thing about the international stamp market, but he certainly knew the value of a good gimmick: After making an initial round of modest stamps that depicted yaks and monasteries, Todd's ideas grew more zany. There were stamps made from silk, some scented with perfume, and others depicting the Yeti. He made stamps from steel (which rusted) and stamps embedded with 3D technology. Finally, in 1972, Todd introduced the world’s first "talking stamps."

Issued in a colorful set of seven, the talking stamps were technically some of the smallest vinyl records in the world. You could, of course, stick the stamp onto an envelope and drop it off at the post office. But you could also place the stamp on a turntable, drop the needle, and be greeted by the sounds of a Bhutanese folk song, the country's national anthem, or a short narration describing life in the Land of Dragons.

Bhutan produced about 300,000 of these stamps which, for years, prompted eye-rolling from many people in the philatelic community, which considered them tawdry pieces of gimmickry. But that has recently changed. Writing for The Vinyl Factor, Anton Spice says prices have been pushed up “by that geekiest of Venn diagrams between stamp and record collectors.” Today, a set of genuine talking stamps can sell for around $400.

As for the eccentric Todd, his ability to find unusual uses for stamps would continue. "He once tried to found a small kingdom himself, on a deserted coral reef in the South Pacific," The New York Times wrote in a 2006 obituary. "Its entire infrastructure was to be built on postage stamps. His dream was dashed, he later said, after Tongan gunboats blew his island paradise to ruins.”