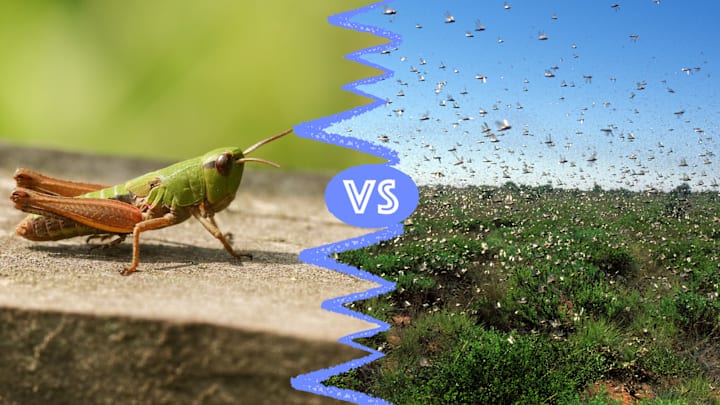

When conditions are just right, swarms of winged, ravenous insects descend upon unlucky parts of the world. They wreak havoc on agriculture, consuming fruits, vegetables, and almost any type of plant matter they can sink their mandibles into. For farmers impacted by the pests, the particulars of what to call them are likely far from their minds. For the rest of us, however, the question is worth pondering: Do these insect invasions comprise locusts or grasshoppers, and what's the difference between the creatures?

Anatomy of a Swarm

In a 2010 article on locusts published in the Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, Alexandre Latchininsky, extension entomologist for the State of Wyoming, explained that “all locusts are grasshoppers but not all grasshoppers are locusts.” He defined locusts as “short-horned grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae), distinguished by their density-dependent behavioral, physiological, and phenotypic polymorphism.”

The phenotype mutability refers to the fact that for some subspecies of locusts, the different stages of life are marked by different colors and even body shapes. However, it is the behavioral aspect—the mass grouping together—that is most notable. The act of swarming, or exhibiting a so-called “gregarious phase,” is the most obvious characteristic that identifies a subspecies of grasshopper as a locust.

Latchininsky explained in his paper that “out of more than 12,000 described grasshopper species in the world, only about a dozen exhibit pronounced behavioral and/or morphological differences between phases of both nymphs and adults, and should be considered locusts.” And in fact, the tendency to swarm together is a relatively recent phenomenon in grasshopper evolution.

Identity Crisis

Such swarms can appear around the world. In 2014, locusts swarmed New Mexico in clouds so thick they showed up on the radar like, well, real clouds.

“It is a nuisance to people because they fly into people’s faces while walking, running, and biking,” John R. Garlisch, extension agent at Bernalillo County Cooperative Extension Service, told ABC News. “They are hopping into people’s homes and garages, they splatter the windshield and car grill while driving, and they will eat people’s plants.”

That New Mexico swarm was anamolous in the insect world. It consisted of members of the Acrididae family, which are the non-swarming members of the grasshopper designation. Latchininsky tells Mental Floss that this has happened roughly a dozen times in evolutionary history. However, he cautions that, “these occasional gatherings do not mean that these grasshoppers are locusts! There are only a dozen or so true locust species in which the increase of density causes behavior changes followed by physiological, morphological and other phenotype changes.” Based on extenuating factors—the previous year's monsoon season coupled with a dry winter—the 2014 phenomenon seemed to be a case of too many grasshoppers in too little space as opposed to a proclivity to swarm.

Still, Latchininsky speculates that it, “may be a first evolutionary step towards this species becoming a locust in a distant future.”

Grasshoppers vs. Locusts Cheat Sheet

Category | Appearance | Behavior | Diet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Grasshoppers | Group | Large hind legs; green to brown; wings | May or may not have a swarming phase | Plants |

Locusts | Subgroup | Large hind legs; green to brown; wings | Has a swarming phase | Plants |

Read More Stories About Animal Differences:

A version of this article was originally published in 2014 and has been updated for 2024.