The body of President George H. W. Bush will be transported by train along a 70-mile route to College Station, Texas, where it will be taken to its final resting place at the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum at Texas A&M University. The train—Union Pacific 4141, named for the 41st president—is painted robin's egg blue (just like Air Force One) and will tow a special transparent viewing car, allowing the public one last chance to pay their respects to the former head of state.

It's the first time a president's body has been moved by funeral train in almost 50 years.

Funeral trains, however, used to be something of a tradition for departed politicians: Presidents Abraham Lincoln, James A. Garfield, Ulysses S. Grant, William McKinley, Warren G. Harding, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower were all transported to their final resting places by a ceremonial train. (As were other government figures, including Robert F. Kennedy, Douglas MacArthur, and Frank Lautenberg.)

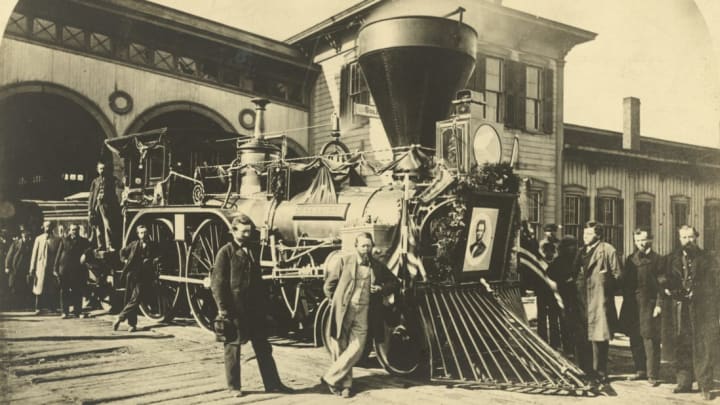

Lincoln's funeral train, the first, was arguably the most memorable. Traveling 1654 miles from Washington D.C., to Springfield, Illinois, the train chugged at a steady speed of 20 mph and stopped at 180 cities over the course of 13 days. The steam engine featured a portrait of Lincoln at the front and carried nine cars covered in elaborate mourning bunting. According to Olivia B. Waxman at TIME, "When it was in transit, a train traveling 30 minutes ahead of the Lincoln Special sounded a bell to alert those in the area that the funeral train was approaching. Those who could only see it at night camped out at bonfires along the route." Millions of people turned out to show their respects.

The next presidential funeral train was for another head of state who sadly also succumbed to gunshot wounds—James A. Garfield. According to the James A. Garfield National Historic Site blog:

"All along the route mourners stood at trackside, heads bowed as the train went by and church bells tolled. Bridges and buildings were draped in black. At Princeton, New Jersey, students scattered flowers on the track and then retrieved the crushed petals after the train had passed to keep for souvenirs. The train was met in Washington by the Chief Justice, Garfield's entire cabinet, and Presidents Grant and Arthur."

In many cases, the funeral trains traveled through places beloved by the presidents. Ulysses S. Grant's train was saluted as it passed through West Point. McKinley's train made haste to reach his beloved home in Canton, Ohio. (Many onlookers, not content to just bring flowers, made mementos by placing coins on the tracks and watched as the train flattened them.)

Meanwhile, FDR's funeral train—which embarked on a nine-state, three-day ride—carried much more than the president's remains: It also carried some of the most important people in government, including Roosevelt's family, the vice president and his family, every Supreme Court Justice, and most of the administrative cabinet. According to the MacMillan synopsis of Robert Kara's book FDR's Funeral Train, "Many who would recall the journey later would agree it was a foolhardy idea to start with—putting every important elected figure in Washington on a single train during the biggest war in history."

In some cases, the deceased had a special connection to the train itself. Eisenhower's body was transported in a car named "The Old Santa Fe." It was a familiar place: Ike had ridden the same car when he made his first campaign speech in 1952. Similarly, Bush—a train lover—had been acquainted with his funeral train for more than a decade, having given the 4300-horsepower locomotive his seal of approval back in 2005. At the time, he even gave the train a two-mile test drive and called it, "The Air Force One of railroads."