5380565974001

Herman Melville had everything a young author could dream of. By the age of 30, he’d traveled the world and written five books, including two bestsellers. He’d married the daughter of a prominent judge, and he owned a beautiful farmhouse. He hobnobbed with the literati. Strangers asked for autographs.

Then he wrote Moby-Dick and ruined everything.

Today, the book is often hailed as the Great American Novel, an epic D. H. Lawrence called “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world.” But in Melville’s time, it was a total flop. Readers couldn’t comprehend the difficult narrative. Critics dismissed it as the ravings of a madman. When Melville tried to mend his image with a follow-up, titled Pierre, the reviews were equally brutal, and the work cemented his reputation as a lunatic. At just 33, Melville was finished. When he died in 1891, at the age of 72, people were shocked—not because he’d passed away, but because they thought he’d been dead for decades. It would take half a century—and a bored academic—to resurrect the author’s legacy.

THE WRITER AT SEA

In 1839, a 20-year-old Melville boarded a merchant ship docked in New York City and voyaged to Liverpool as a cabin boy. The trip kindled his spirit for adventure. Two years later, he joined a whaler named Acushnet and set off for the Pacific. That’s when he learned how terrifying a 70-foot sperm whale could be.

A full-grown whale can weigh as much as eight elephants. Fifty-two teeth—each nearly the length of a bowie knife—ring its lower jaw. The fluke dwarfs the size of most minivans and can smash a small whaleboat into splinters. And while the behemoths are generally timid, over the years, they’ve given whalers plenty of horror stories to tell. Two in particular stuck with Melville.

The first concerned a seaman named George Pollard Jr., captain of the whaleship Essex. In November 1820, a sperm whale attacked Pollard’s ship in the Pacific, about 2,000 miles from shore. The 85-foot-long leviathan barreled into the boat headfirst and rocked the crew to their knees. When the men heard wood crack below, they rushed into the ship’s hold: The Essex was leaking, but the damage looked repairable.

Then the whale returned.

This time, the animal tore through the waves twice as fast, snapping its jaws as it thundered back into the bow. Seawater gushed in, and the ship tilted on its side. The Essex slowly slipped beneath the waves, leaving Pollard and his men lost at sea.

Melville also learned about Mocha Dick, a vicious whale that had attacked at least 100 vessels and sent 20 boats to the ocean bottom. Lore of the whale fueled nightmares: Rusting harpoons protruded from its back, a ghastly reminder of how many men had failed to kill him—and died trying.

In 1838, Mocha Dick attacked an American ship after its sailors killed a calf and its mother. Enraged, Mocha smashed apart one of the whaleboats, but not before a sailor managed to plant a harpoon in his back. Mocha dove and dragged the man under, but it was a mortal blow. When the whale surfaced, the sea was stained crimson. A dark clot of blood frothed from its spout. Its last breath showered the sailors in red mist. Mocha Dick was finally dead. A decade later, Melville would attempt to make him immortal.

WHALE OF A TALE

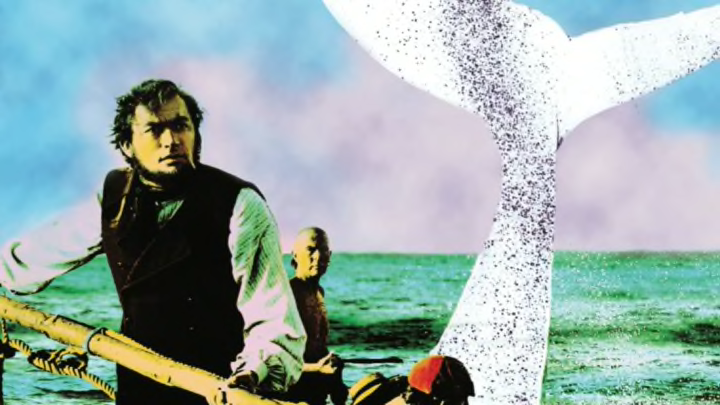

ALAMY

After four years of hitchhiking the oceans and collecting adventures—including an escape from Polynesian cannibals and a stint in a Tahitian jail—Melville left the sea to embark on a literary journey. His first book, Typee, was an immediate bestseller, making him one of America’s most beloved adventure writers. His second, Omoo, was also a hit. Both were rollicking yarns—easy and fun to read. Inspired by these early successes, Melville became a literary machine and produced nearly a book a year. By 1849, he’d already started his sixth novel: Moby-Dick.

Early drafts of Moby-Dick began like the rest of Melville’s stories, as a playful romp on the high seas. But that same year, the author made a life-changing decision: He moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he befriended author Nathaniel Hawthorne. The relationship would become one of the most intense literary bromances of all time.

Melville worshipped Hawthorne. The two spent hours together talking philosophy, literature, and life. As their friendship grew, Melville became increasingly enamored with his new mentor. When Hawthorne suggested he rewrite the merry sailor’s tale into a metaphysical monsterpiece, Melville agreed. It was time to quit penning pabulum and start crafting something literary! At Hawthorne’s urging, Melville missed his deadline. He put the manuscript aside for a while to study Shakespeare and Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle. Within a year, Moby-Dick was transformed. When Melville sent it to his publisher in 1851, he proudly wrote to Hawthorne, “I have written a wicked book and feel as spotless as a lamb.”

What he submitted was a 135-chapter tome. The story follows a sailor—call him Ishmael—aboard the Pequod, a whaleship commanded by the monomaniacal, peg-legged Captain Ahab. Looking for revenge, Ahab scours the sea for an albino sperm whale that chewed off his leg long ago. His obsession to find and fight the monster drags everyone but Ishmael to Davy Jones’s locker. But what sounds like an adventure is a plot freighted with symbolism and wild digressions cataloging practically everything about the Yankee whaling industry.

Reviews were merciless. The London Athenaeum called Moby-Dick “trash belonging to the worst school of Bedlam literature.” The London Literary Gazette said the story made readers “wish both [Melville] and his whales at the bottom of an unfathomable sea.” The New York United States Magazine and Democratic Review charged Melville with crimes against the English language.

The poor reception wasn’t entirely Melville’s fault. The British first edition accidentally omitted the epilogue. The publisher also deleted 35 crucial passages to “avoid offending delicate political and moral sensibilities.” But those excuses linger only as a footnote. Critics and fans alike had expected a wild ocean adventure. Instead, Melville gave them a 635-page philosophical brick.

Just 3715 copies of Moby-Dick were sold in Melville’s lifetime. The book earned him a measly $556.37 in the United States. His popularity plummeted—and so did his bank account. “Dollars damn me,” he griped earlier to Hawthorne. “What I feel most moved to write, that is banned—it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I cannot.” Within a year, Hawthorne stopped writing back. Their friendship dissolved.

In 1863, Melville returned to New York City and became a customs inspector. He held the job for the rest of his life, quietly writing poetry in his spare time. In 1867, Melville’s oldest son killed himself, sending the already alcoholic author spiraling into depression. The day after Melville died, his obituary appeared in just one newspaper. It was a paltry six lines long. Melville would have to spend three decades rotting in a pine box before critics realized there was more to his story.

REVISITING MELVILLE—AND MOBY-DICK

Things changed in 1919, when Raymond Weaver was given an assignment he didn’t want. A Columbia graduate student, Weaver was schmoozing with Professor Carl Van Doren at an annual spring dinner when they began discussing the forgotten author. Van Doren had moonlighted as the editor for The Nation and knew Melville’s 100th birthday was coming soon. He wanted to print a short tribute in the magazine and asked Weaver to write it.

Weaver was hesitant. He’d tried to read Typee in college and hated it. But after some prodding—and the promise of a paycheck—he caved. Calling the gig “child’s play,” Weaver dug through Columbia’s library looking for information. But he was quickly surprised by what he found ... and what he didn’t. Melville’s oeuvre was huge: nine novels, scores of short stories and poems—but nothing on his life. Weaver had to hunt for Melville’s personal letters and memos on his own. By the end of the chase, two years later, he had written Melville’s biography.

One discovery in particular recharged scholarly interest in Melville’s work: a yellowing manuscript tucked inside a tin bread box, unearthed by Melville’s granddaughter. Recognizing it was an unpublished novella, Weaver had it printed. The work is now one of Melville’s most beloved narratives—Billy Budd.

The timing couldn’t have been better. In the 1920s, academics were trying to assemble America’s literary canon. When they rediscovered Moby-Dick, they realized it had everything they were looking for: artful prose, iconoclastic ideas, rich symbolism, universal themes. It melded fiction with fact. It was experimental. It defied genre. Critics finally understood why Moby-Dick had been so poorly received—it was 70 years ahead of its time.

By the 1930s, Melville had become king of the American canon. William Faulkner hung a print of Captain Ahab in his living room. Ernest Hemingway pegged Melville as the literary genius to beat. Moby-Dick would inspire countless authors, including Albert Camus, Norman Mailer, Ray Bradbury, Jack Kerouac, Cormac McCarthy, and Robert Pirsig.

The book’s cultural footprint remains deep. The story has been adapted for film more than six times and for countless staged plays. It has been referenced far and wide, from The Flintstones to a Marvel comic book to a rock song by Led Zeppelin. The phrase “white whale” is everyday business lingo. Even Starbucks pays homage, taking its name from Ahab’s first mate.

For his part, Melville was always convinced people would warm up to his work eventually—it would just take time. While editing Moby-Dick in 1850, he prophesied, “It is better to fail in originality, than to succeed in imitation. He who has never failed somewhere, that man cannot be great.”

This story originally appeared in an issue of mental_floss magazine. Subscribe here.