In the late 1950s, the future was up in the air. The space race was just getting started, and the U.S. military was working on missiles that could reach around the world—and even to the Moon. The U.S. government didn’t just see new flight capabilities as military priorities, though. It also thought they could be used to carry mail, as we recently learned from Today I Found Out. Yes, the Postal Service once tried sending letters by missile mail.

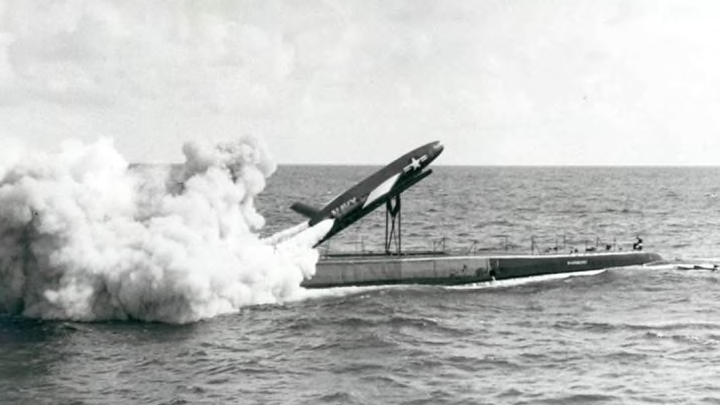

In June 1959, the U.S. Navy sent 3000 letters on a guided missile toward a naval auxiliary air station in Mayport, Florida. Launched from the USS Barbero, a submarine that was stationed 100 miles off the U.S. coast in international waters, the 36-foot Regulus I missile made it to Mayport in 22 minutes. Held in two metal containers in what was supposed to be the missile’s warhead chamber, the letters on board were copies of a letter from Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield to then-President Eisenhower, Vice President Richard Nixon, individual representatives of Congress, members of the Supreme Court, the crew of the Barbero, and more. The letters carried regular mail stamps—“not even air mail,” as the AP story that day noted.

The Postal Service heralded it as the first successful delivery of mail by missile. (There had been previous attempts, like a thwarted 1936 delivery on a rocket-powered plane across a lake between New York and New Jersey [PDF]. Despite several attempts, that one never fully made a successful delivery.) But “delivery” was a bit of an overstatement: Most of those letters had to be sent by regular mail service at a post office in nearby Jacksonville, since the 3000 recipients weren’t sitting around at a naval base in Florida waiting for their letter.

“Now that we know we can do it,” Summerfield told the press, “we plan a series of discussions to determine the practical extent to which the method can be used and under what conditions.” It never did become practical, as we now know. Summerfield’s successor, J. Edward Day, killed the program, pointing out that the letters sent from the USS Barbero ended up taking some eight days to reach their intended recipients. Not exactly rocket speed.

Even if missile mail wasn't a financially or logistically feasible way to send the mail on a regular basis, the test likely proved worthwhile just for the bragging rights. “Ostensibly an experiment in communication transportation,” Nancy A. Pope writes on the National Postal Museum’s blog, “the Regulus’ mail flight sent a subtle signal that in the midst of the Cold War, the U.S. military was capable of such accuracy in missile flight that it could be considered for use by the post office.”

And it wasn’t so strange that the USPS was trying out newfangled technology in its quest to get mail across the country as fast as possible. As the rail industry declined, it was becoming more expensive and less efficient to send mail by train. Throughout the early 20th century, the U.S. Postal Service looked into a number of alternatives, including post office buses that would travel from town to town sorting mail along the way, intercity helicopter mail, and other ideas that harnessed ways of delivering mail that would have been unthinkable a few decades before. But in the end, improving roads to make it easier to send trucks around the country proved a better financial plan than using guided military missiles.

[h/t Today I Found Out]