Tom Molineaux found freedom with his fists.

Regarded as America's first great prizefighter, very little is known about Molineaux’s early life. The most common account, however, says that he was born a slave in Virginia sometime around 1784. The local plantation owners took amusement in pitting their enslaved people against each other in bare-knuckle boxing matches, and Molineaux showed a knack for the sport. One day, he won a match that earned his master a huge sum in bets, and was consequently granted his freedom.

(There’s an unsubstantiated rumor that George Washington, a neighboring plantation owner, might have given Molineaux a few pointers in the ring. While that is almost certainly a fabrication, Washington did in fact know a great deal about combat sports such as wrestling; Sports Illustrated called him “a master of the British style known as collar and elbow.”)

After gaining his freedom, Molineaux moved north to New York City around 1804 and began honing his bare-knuckle boxing skills. Details are scarce, but it’s obvious that the young pugilist carved out a name for himself, as he soon earned the title of “Champion of America.”

After five years, Molineaux decided to take his talents across the pond to England. “He was the first American to rise to the eminence of an international challenger,” journalist Paul Magriel wrote in a 1951 edition of the journal Phylon [PDF].

But Molineaux wasn't just hungry for new competition. In Britain, there was big money in boxing. Though the sport was technically illegal, it was well-respected and well-attended. It also had a set of well-defined rules, which Brian Phillips wrote about in a fantastic piece for Grantland:

"Bouts were held outdoors, on bare ground, in rings marked off from fields. The fighters wore no gloves, which probably made them safer. (Gloves were introduced to protect the hands, not the head, and allowed fighters to punch harder.) But rounds didn’t end until one man or the other went down. And there was no limit to the number of rounds that could be fought. After a fall, fighters had 30 seconds to return to the scratch, a mark in the middle of the ring."

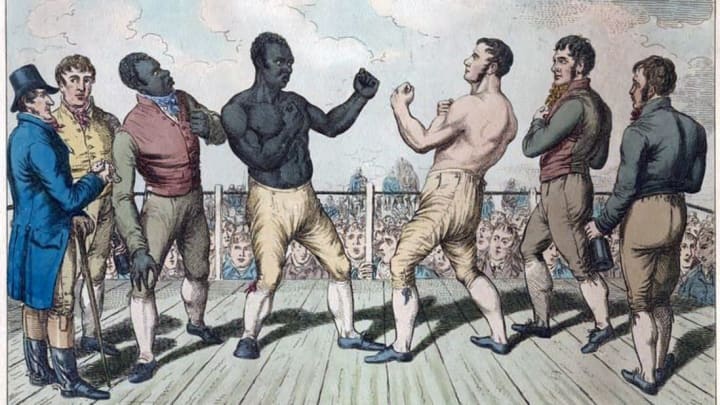

Arriving in England, Molineaux had one goal: To fight Tom Cribb. Cribb, who was born near Bristol, England, was considered Europe’s best boxer and routinely drew tens of thousands of spectators to his matches. He was also incredibly tough. According to Phillips, “he reportedly trained by punching the bark off trees.”

In London, Molineaux met a fellow American boxing aficionado—and ex-slave—named Bill Richmond. Richmond, who was considered one of the world’s first black sporting celebrities, was also a highly in-demand trainer. And he agreed to take Molineaux under his wing.

The duo was a perfect fit. With Richmond’s help, Molineaux began to vanquish his opponents fight after fight after fight. In one match, he beat a man so badly that it was impossible to discern his facial features. “The amateurs were completely astonished at the improvement exhibited by Molineaux, and the punishment he dealt out was so truly tremendous, and his strength and bottom so superior, that he was deemed a proper match for the champion, Tom Cribb,” wrote Pierce Egan, a celebrated journalist of the time, in his book Boxiana.

The momentous match was arranged for December 18, 1810. Immediately, the bout's implications were freighted by racism and nationalism. “Some persons feel alarmed at the bare idea that a black man and a foreigner should seize the championship of England, and decorate his sable brow with the hard earned laurels of Cribb,” one media outlet claimed, according to the book Pugilistica.

On the day of the fight, rain poured down. More than 5000 people attended anyway, including a gaggle of the first professional sportswriters. Long before the first punch was thrown, the pro-Cribb crowd began hurling racist invectives at the black American fighter.

Molineaux seemed undeterred. Round after round, he knocked the English champion down. At one point, Molineaux held Cribb in a legal headlock, and the fight's action stalled. Dozens, possibly hundreds, of impatient fans stormed the ring. The scrum injured—and possibly broke—a few of Molineaux’s fingers.

The American continued to dominate anyway.

By the 28th round, the afternoon’s wagers—which had started at 4 to 1 in Cribb’s favor—were now even. According to Egan, “In the 28th round, after the men were carried to their corners, Cribb was so much exhausted that he could hardly rise from his second's knee at the call of 'Time.'" It was clear that Molineaux was on pace to win.

In fact, many people believe he should have already been declared the victor. In the 27th round, Cribb fell and failed to get back up after the required 30 seconds. By all means, Molineaux should have been celebrating. But Cribb’s minders distracted the refs and managed to buy enough time for Cribb to regain both his consciousness and his composure. Whether they were complicit or just clueless, the refs let the time violation slide and the fight continued [PDF].

Shortly after, the momentum shifted.

Cribb landed a few lucky punches. Molineaux, whose eyes had swollen over, began to stagger. After 44 rounds, the American quit and Cribb was declared the winner. The crowd went nuts, leading Pierce Egan to call the whole event, "[T]he most dreadful affront to British sportsmanship ever witnessed."

A few days later, Molineaux sent Cribb a letter blaming the loss on the weather and asking for a rematch. A second fight, which occurred approximately nine months later on September 18, 1811, was attended by more than 15,000 people. This time, Cribb out-trained the American and defeated Molineaux in 11 rounds.

But history had already been made. The first match had secured Molineaux a hallowed place as one of the sport’s top athletes, and in 1997, he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.