Denny O’Neil kept thinking about Larry the Lobster. O’Neil, who served as the group editor of the Batman family of comic book titles for DC Comics in the 1980s, was at a writer’s retreat in upstate New York in 1988 when he and other staffers began discussing the best way to address growing reader dissent with the current incarnation of Robin. Batman’s newest sidekick—a street urchin named Jason Todd—was sullen and moody, a sharp contrast to the gleeful energy of former ward Dick Grayson. Fans called him whiny and petulant. Measures needed to be taken.

During the conversation, O’Neil suddenly remembered a 1982 skit from Saturday Night Live in which cast member Eddie Murphy threatened to boil a lobster named Larry on air unless viewers phoned in and begged for clemency. Or, Murphy told them, they could dial a separate 900 number to cast a vote for his death. The following week, Murphy announced the lobster had earned a stay of execution. He ate it anyway.

O’Neil wondered if the same gimmick could be applied to comics. If fans hated Robin so much, O’Neil thought, then perhaps they should feel culpable for killing him.

Death in comics was nothing new. Saddled with decades of continuity and running the risk of repeating themselves, comics writers often turn to tragedy to shake up the status quo. Comic book covers of the 1950s—the clickbait of their time—often hinted at a demise inside, though it was usually a case of misdirection. In 1973, Marvel allowed Spider-Man’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, to plummet to her death during a scuffle with the Green Goblin. (In the next issue, the Goblin, a.k.a. Norman Osborn, met his maker.) In the 1980s, one iteration of Captain Marvel succumbed to that most human of weaknesses: cancer.

DC had enlisted the Grim Reaper, too, killing off the Flash and Supergirl during their 1986 Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover that attempted to sort out the publisher’s confusing timelines.

It was the clean slate of Crisis on Infinite Earths that allowed O’Neil to improve upon Jason Todd’s origin story. Originally introduced in Batman #357 (1983) as a trapeze artist whose parents fell to their death, Todd’s background was a virtual carbon copy of Dick Grayson’s, who had first appeared as Robin back in 1940. After more than 40 years as the Dark Knight's sidekick, Grayson came into his own and adopted the mantle of Nightwing, another player in the DC Universe. Which left a spot open for a new Robin. Enter Todd who, under O'Neil's supervision, was first discovered trying to liberate a wheel from the Batmobile. Impressed with the kid’s courage, Batman enlisted him to bust a child crime ring. After a bit of superhero training, he became an official costumed sidekick.

Jim Starlin, who had recently come on board as writer for the main Batman title—and who had killed off Captain Marvel for Marvel—had never particularly liked any version of Robin; he preferred to depict Batman as a troubled loner. While Starlin had advocated for Robin’s demise as far back as 1984, this latest iteration was especially grating to him, as Todd often ignored orders and brooded incessantly. When DC floated the idea of having one of their characters contract HIV, it was Starlin who repeatedly suggested giving Robin the virus.

The publisher didn’t go for that, but O’Neil’s idea to have readers cast their own votes gained momentum within the company. Starlin needed no convincing and wove a four-issue plot, “Death in the Family,” in which Todd discovers his biological mother is alive and working in Ethiopia. He travels to see her, but realizes she has been recruited by the Joker to sell stolen medical supplies. Todd's only choice is to confront the iconic villain—a showdown that sees him beaten nearly to death with a crowbar and left to die in an explosion.

An ad at the conclusion of the issue breathlessly told readers that Robin’s ultimate fate was in their hands. “Robin will die because the Joker wants revenge, but you can prevent it with a telephone call,” it read. Dialing one 900 number cast a vote for his survival; dialing another would help seal his doom. Each call cost 50 cents.

The lines were only open for a 36-hour period on September 16 and 17, 1988. Approximately 10,614 calls were received. Of those, 5271 backed a second chance, while 5343 threw dirt on Todd’s face. Robin would die, executed by a margin of just 72 votes—though that may not have represented 72 people. At least one anti-Robin activist admitted to calling in four times to cement the sidekick's death.

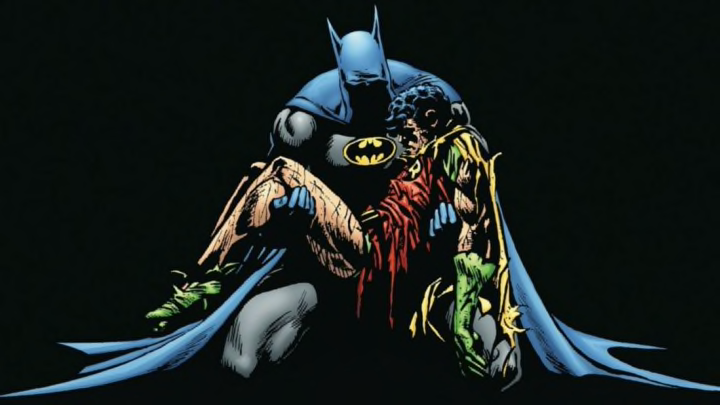

In Batman #428, which hit stands that October, the Dark Knight finds a bloodied Todd in the rubble. (Two endings had been prepared by Starlin and artist Jim Aparo; the winning conclusion was the one rushed to press.) To make matters worse, Batman discovers that the Joker has been named an ambassador to the United Nations by the Ayatollah Khomeini and now has diplomatic immunity.

Starlin got his wish. So did the majority of fans. But DC wasn’t prepared for what happened next.

With the mainstream media not quite hip to the fact that death is often not a permanent condition in comics, hundreds of headlines that fall ran with the news that Batman’s perennial sidekick had perished. “Holy Hearse, Batman!” read the Arizona Daily Star. Press calls flooded into DC’s offices. O’Neil gave interviews for three days straight, and was eventually cut off by a concerned DC public relations employee who feared that all the attention was reflecting poorly on the company.

For most of the public, the “Robin’s Dead” notices were scanned without much regard for which Robin died—it was the aloof Todd who had met his maker, not the beloved Dick Grayson. DC’s marketing arm was jolted, as thousands of lunchboxes, shirts, and toys were now doubling as memorials for Batman's deceased sidekick. (For better or worse, Robin was not a part of Tim Burton’s Batman, which was set to arrive in theaters just seven months later.) Starlin later said, perhaps only half-jokingly, that O’Neil took credit for the idea until executives grew annoyed, at which point Starlin became the man who killed the Boy Wonder.

Batman #428 and the other connected issues sold out, with the issues going for $20 to $40 apiece in the collector’s aftermarket. DC would later use the death trope to even greater effect with their 1993 “Death of Superman” saga, selling millions of copies, some of them bagged with a black armband for proper mourning.

Superman returned, of course. So did Todd. He was later revealed as the Red Hood, a Batman nemesis who is slated to appear on the DC Universe streaming series Titans alongside original Robin Dick Grayson. Still, Todd's death seemed to teach O’Neil a lesson about the enduring appeal of comic mythology and the responsibility that goes along with it.

“It changed my mind about what I did for a living,” O'Neil said. “I realized that, no, I am in charge of post-modern folklore. These characters have been around so long and so ubiquitously that they are our modern equivalent of Paul Bunyan and mythic figures of earlier ages.”

Just because it was O'Neil's idea to let fans decide Robin's fate doesn't mean he was in favor of his demise. During the brief window the phone lines were open, O’Neil picked up his phone. He dialed the 900 number in support of saving him.