Though no territory changed hands after the War of 1812, the conflict was a defining struggle for Canada, the United States, and Indigenous peoples across North America. Here are 12 things your history teacher might not have told you about the war that transformed a continent.

1. The War of 1812 was caused by repeated violations of U.S. Naval rights.

Before the War of 1812, Britain was mired in a series of wars against France, and both countries issued various orders to try to keep the United States from trading with the other that resulted in merchant ships being captured. Great Britain also used impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy to keep its ships fully staffed. After years of conflict, President James Madison finally decided that enough was enough and asked Congress for a formal declaration of war.

2. The War of 1812 almost didn't happen.

Article I, Section Eight of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the sole power to declare war, and it was the first time the legislative body had exercised that power. But it was an extremely close vote: Madison's party, the Democratic-Republicans, was divided over the prospect of starting a war with a global superpower like Great Britain. Across the aisle, the rival Federalist party was uniformly against the idea.

Federalists dominated New England, whose seafaring communities depended on trade with the British. (The party also had some strong reservations about France's government and its leader, Napoleon Bonaparte.) So when the Madison-backed war resolution came up for a vote in Congress, not a single Federalist supported it. The measure passed anyway: On June 4, the House of Representatives voted 79 to 49 in favor of going to war. The Senate responded in kind on June 17, with 19 yes votes and 13 nos. No other declared war in U.S. history has ever been approved by such a narrow margin in Congress.

3. At the beginning of the War of 1812, America's Navy had just 16 ships.

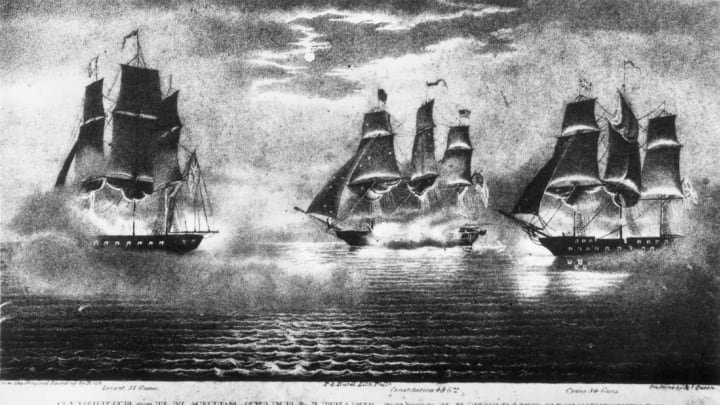

On paper, the U.S. Navy was no match for the gigantic Royal Navy, which had hundreds of active warships. The U.S. Navy had just 16 ships, including the 12-gun USS Viper and the 44-gun USS Constitution.

But Great Britain's maritime forces were stretched thin by the Napoleonic Wars, and since defeating Napoleon was a bigger priority than embarrassing James Madison, the British initially sent just nine frigates to fight the Americans. According to Canadian naval historian Victor Suthren, the chosen vessels were "not [Great Britain's] best ones and not manned by their most experienced crews, many of whom had been forced or impressed into service." Conversely, the American frigates were newer, larger, and well-manned.

The U.S. Navy had some morale-boosting victories early in the war. On August 19, 1812, the USS Constitution met and defeated the HMS Guerriere 400 miles east of Nova Scotia. Very little damage was done to the American vessel, which earned the nickname "Old Ironsides." That December, the ship scored another win, this time over the HMS Java frigate. But Old Ironsides didn't steal all the glory in battle: The USS United States beat the HMS Macedonian on October 25, 1812.

America's naval victories became scarcer after the British blockaded the eastern seaboard in mid-1813, but water battles continued to break out. For example, nine U.S. ships memorably defeated six British vessels at the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813.

4. The War of 1812 confirmed that Canada didn't want to be part of the United States.

In April 1812, Thomas Jefferson wrote that "The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching; & will give us experience for the attack of Halifax the next, & the final expulsion of England from the American continent." Secretary of War William Eustis concurred, saying "We can take [Canada] without soldiers. We have only to send officers into the provinces and the people, disaffected towards their own government, will rally round our standard." The plan was to invade Canada in three waves, striking the country from Detroit, the Niagara border, and Lake Champlain.

But instead of being greeted with open arms, American troops met strong resistance from the locals, a hodgepodge of French-Canadians, Native Americans, and British loyalists who'd fled the U.S. after the Revolutionary War. The fact that U.S. forces—like their transatlantic counterparts—tended to loot captured villages did not endear them to the citizenry. Canadians were especially appalled by the invasion and burning of York (present-day Toronto) on April 27, 1813, as well as the burning of Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) in December. Resistance to the American military became a nation-defining cause for Canada's people, who celebrate the War of 1812 to this day.

5. Tecumseh and his Native American confederacy had a tremendous impact on the War of 1812.

Born in March 1768, Tecumseh was a Shawnee chief who had lost his father in Lord Dunmore's War. He spent several years building a military alliance of over two dozen Indigenous Nations with the goal of ending the westward expansion of white settlers once and for all. Seven months before the U.S. Congress declared war on Great Britain, Tecumseh's confederacy fought future president William Henry Harrison at the Battle of Tippecanoe in what's now northern Indiana (though Tecumseh himself wasn't there).

After the battle, Tecumseh's confederacy forged on. In a politically expedient move, Tecumseh allied himself with the British once the War of 1812 broke out. Native American forces helped Great Britain take Detroit and repel American invaders from Queenston, Ontario. They also facilitated the capture of over 300 U.S. soldiers at the Battle of Beaver Dams. But after Tecumseh was mortally wounded at the Battle of Thames (1813), his confederacy unraveled.

6. Detroit was captured by the British during the War of 1812—and remained captured for over a year.

Detroit was a rising frontier town with a population of around 800 when the War of 1812 began. Inside, there was a thick-walled fortress where General William Hull—Michigan's territorial governor—set up a base of operations with his son, his daughter, his grandchild, and a force of over 2000 American militiamen and regular army soldiers. On August 16, 1812, Hull surrendered to a numerically inferior contingent of British and Native American men who had surrounded Fort Detroit. The general had been worried about losing his supply lines and falsely believed that he was outnumbered. Plus, Tecumseh flat-out terrified him. "[Hull] had an inordinate fear of the Indians," historian A.J. Langguth explained in the PBS documentary The War of 1812. "He was convinced that … if they were unleashed on his family or his troops, it would be the worst kind of massacre."

Fort Detroit wasn't retaken by the Americans until September 1813. The following year, Hull was court-martialed and found guilty of cowardice, neglect of duty, and conduct unbecoming of an officer. For these crimes, Hull received a death sentence but was then pardoned by President Madison.

7. The White House burned during the War of 1812, but the patent office was spared.

British General Robert Ross and Admiral Alexander Cochrane arrived in Maryland on August 19, 1814 with 4500 veterans fresh from the Napoleonic campaigns. On the 24th, having muscled past 5500 U.S. militiamen, they made it to Washington, D.C., where they torched the White House mere hours after President Madison and his wife left town. They also burned the Capitol Building, which contained the Library of Congress along with the chambers used by the Supreme Court, the Senate, and the House of Representatives.

The only government building the Brits didn't put to the torch was the U.S. Patent Office. Dr. William Thornton, Superintendent of Patents at the time, had hundreds of important documents rushed out of the city prior to the attack. Then, when the British came, he (allegedly) persuaded them not to immolate the Patent Office.

Tradition has it that Thornton put himself in front of a cannon aimed at his building and shouted "Are you Englishmen or Goths and Vandals? This is the Patent Office, the depository of ingenuity of the American Nation in which the whole world is interested. Would you destroy it?" The British backed off. (Sadly, the office burned down anyway 22 years later due to an accidental fire that consumed 10,000 patent documents.)

8. "The Star-Spangled Banner" was written during the War of 1812.

In September 1814, an American lawyer named Francis Scott Key met with Ross and Cochrane to negotiate the release of his friend Dr. William Beanes, who had been taken prisoner. The British higher-ups agreed to let the doctor go, but for the sake of military secrecy, they forbade Key and Beanes from going ashore until after a planned attack on Baltimore had ended.

That's how Key was able to witness the bombardment of Fort McHenry, a star-shaped bastion, completed in 1802, that faced Baltimore Harbor. The fort withstood a massive assault on September 13 and enabled the Americans to successfully defend Baltimore. From his vantage point onboard a truce ship, Key watched as the 42-by-30-foot flag above the fort remained in place even amidst heavy cannon fire. Much to his delight, it was "still there" the next morning (though it's thought that during the actual battle the giant flag was replaced by a smaller "storm flag").

The inspired lawyer went on to write a poem set to the melody of "To Anacreon in Heaven," the theme song of a well-known London gentlemen's club. Key's original title for his poem was "Defense of Fort McHenry," but it was later renamed "The Star-Spangled Banner" by a Baltimore music store. In 1931, it officially became America's first national anthem.

9. More than 4000 former slaves were set free by the British during the War of 1812.

Escaped slaves fought on both sides of the war. Some, like Charles Ball—who escaped bondage, declared himself a free man, and became a member of the American Chesapeake Flotilla before fighting in the Battle of Bladensburg—chose to join the U.S. ranks. Andrew Jackson later commanded almost 900 black troops, a group that consisted of both slaves and free men, at the Battle of New Orleans.

But the British rallied far more ex-slaves to their cause than did the Americans. In 1814, Cochrane issued a proclamation stating that "all those who may be disposed to emigrate from the United States … with their families" could join the British military or become "free settlers to the British possessions in North America or the West Indies." Over 4000 former slaves took him up on that offer. Around 600 emancipated black people served in the British Colonial Marines, taking part in the Burning of Washington and the Battle of Baltimore. Once the war ended, thousands of African Americans who'd fled to Great Britain's military were given land in places like Nova Scotia or Trinidad.

10. Uncle Sam was born during the War of 1812 (according to Congress).

There are a few different explanations for where Uncle Sam came from. The most popular story says he was named after Sam Wilson, a real-life meat packer who lived in Troy, New York. He did business with the American military during the War of 1812, shipping barrels off to hungry soldiers. To designate the containers as United States government property, they were labeled "U.S." Troy residents joked that the "U.S." really stood for "Uncle Sam," which was—supposedly—Wilson's nickname.

Many historians don't buy this particular yarn (evidence has been uncovered for Uncle Sam being a nickname since 1810), but in 1961, Congress passed a resolution acknowledging Sam Wilson as "the progenitor of America's national symbol of Uncle Sam." He received another posthumous honor in the late '80s. September 13, 1989—the 223rd anniversary of Wilson's birth—was proclaimed "Uncle Sam Day" by then-President George H.W. Bush.

11. The War of 1812 led to a permanent split between Maine and Massachusetts.

Even today, Mainers and Bay Staters don't always see eye to eye. The seeds of their rivalry were planted in the late 1640s, when Maine was absorbed into the more populous colony of Massachusetts. Changing demographics put this merger to the test. Following the American Revolution, an influx of new settlers came pouring into the District of Maine. These transplants tended to vote Democratic-Republican while their counterparts down in present-day Massachusetts were mostly Federalists. A rift soon emerged between the state government in Boston and the Mainers under its protection.

The War of 1812 deepened the divide. In July 1814, the Royal Navy captured Eastport, Maine. And that was just the beginning: Within a few short weeks, all of eastern Maine found itself under British occupation. Massachusetts Governor Caleb Strong then made the controversial decision to withhold military relief. Due to an international boundary dispute over Moose Island and surrounding areas, the British continued to occupy eastern Maine until 1818—three years after the war ended. The following summer, Mainers voted to secede from Massachusetts. As a condition of the Missouri Compromise, the free state of Maine was admitted to the Union on March 15, 1820.

12. The War of 1812 ended in February 1815—but one important battle was fought after the Treaty of Ghent was signed.

That would be the Battle of New Orleans, which occurred on January 8, 1815, and launched the political career of future president Andrew Jackson. Though he was outnumbered (and struggling with dysentery), the Major General notched a victory for the United States when he met and defeated 8000 British troops with his 5700-man force of Gulf Coast pirates, Choctaw warriors, free blacks, and American militiamen. The fight is famous for having started after British and U.S. representatives signed the Treaty of Ghent, which officially ended the war when it was ratified that February. Regardless, American voters saw Jackson's triumph as a nationwide cause for celebration.

The Tennessean went from being a little-known southern lawyer and military figure to a national icon almost overnight. When Jackson ran for president in 1824 and 1828, his supporters made sure to emphasize his achievements in NOLA. At Jacksonian campaign events, musicians would play "The Hunters of Kentucky," a popular folk song about the militiamen at the Battle of New Orleans.

13. "Old Ironsides" took a victory lap in 2012.

To honor the 200th anniversary of its victory over the HMS Guerriere, the USS Constitution set sail out of Charlestown, Massachusetts on August 19, 2012, manned by a crew of roughly 65 people along with 150 additional sailors. After a 17-minute trip into Boston Harbor, the ship returned to its home at the Charlestown Navy Yard.