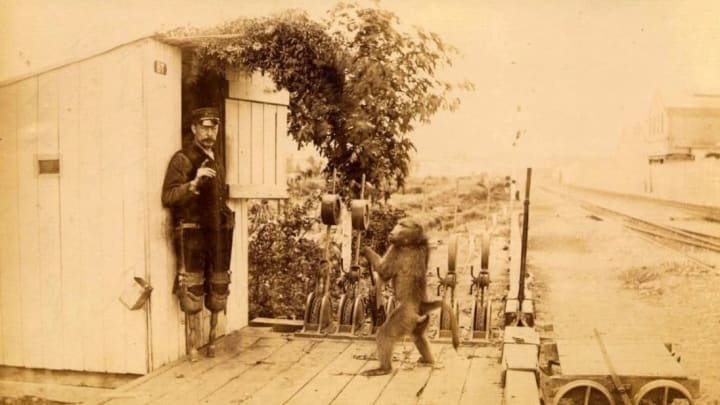

One day in the 1880s, a peg-legged railway signalman named James Edwin Wide was visiting a buzzing South African market when he witnessed something surreal: A chacma baboon driving an oxcart. Impressed by the primate’s skills, Wide bought him, named him Jack, and made him his pet and personal assistant.

Wide needed the help. Years earlier, he had lost both his legs in a work accident, which made his half-mile commute to the train station extremely difficult for him. So the first thing he trained the primate to do was push him to and from work in a small trolley. Soon, Jack was also helping with household chores, sweeping floors and taking out the trash.

But the signal box is where Jack truly shined. As trains approached the rail switches at the Uitenhage train station, they’d toot their whistle a specific number of times to alert the signalman which tracks to change. By watching his owner, Jack picked up the pattern and started tugging on the levers himself.

Soon, Wide was able to kick back and relax as his furry helper did all of the work switching the rails. According to The Railway Signal, Wide “trained the baboon to such perfection that he was able to sit in his cabin stuffing birds, etc., while the animal, which was chained up outside, pulled all the levers and points.”

As the story goes, one day a posh train passenger staring out the window saw that a baboon, and not a human, was manning the gears and complained to railway authorities. Rather than fire Wide, the railway managers decided to resolve the complaint by testing the baboon’s abilities. They came away astounded.

“Jack knows the signal whistle as well as I do, also every one of the levers,” wrote railway superintendent George B. Howe, who visited the baboon sometime around 1890. “It was very touching to see his fondness for his master. As I drew near they were both sitting on the trolley. The baboon’s arms round his master’s neck, the other stroking Wide’s face.”

Jack was reportedly given an official employment number, and was paid 20 cents a day and half a bottle of beer weekly. Jack passed away in 1890, after developing tuberculosis. He worked the rails for nine years without ever making a mistake—evidence that perfectionism may be more than just a human condition.