Despite the incredible labor that goes into their relocation, a number of colossal artifacts have made very long trips after being purchased—or, occasionally, stolen. Here are a few journeys of such enormous objects, from a whole 19th-century bridge to the ancient god of a lost city.

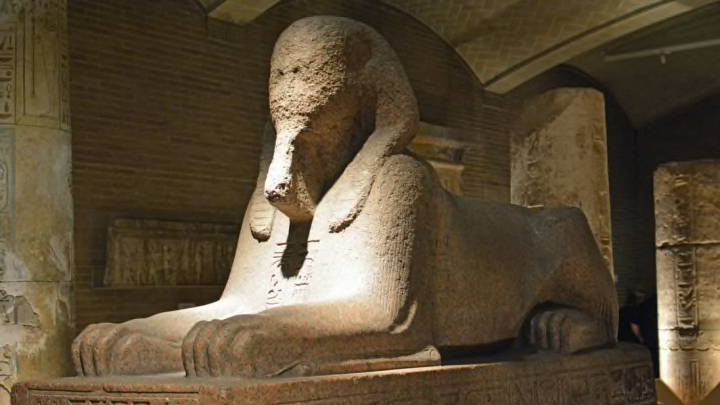

1. AN EGYPTIAN SPHINX

In October 1913, a nearly 15-ton, 3000-year-old sphinx arrived with great fanfare in Philadelphia. From Memphis, Egypt, it had traveled up the Suez Canal, then boarded a German freighter, packed alongside goat skins that were destined for a local leather tannery. Once docked in the United States, a crane hoisted the red granite statue onto a train car. Finally, with the help of an iron-wheeled truck, 10 horses, and 50 workers, it was installed outside the Penn Museum. It was moved inside the galleries in 1926, and it's guarded the collections ever since (although it's currently off-view for conservation work).

2. A STATUE OF JUNO

For a nearly 13-foot-tall, 13,000-pound Roman goddess, Juno has gotten around. With a head sculpted in the 1st or 2nd century CE and a body made a century or two later, the statue's first recorded whereabouts are in the gardens of Rome's Villa Ludovisi. She was sold to Americans Charles and Mary Sprague in 1897, then transported in 1904 to their home in Brookline, Massachusetts. There the marble woman, decked out in flowing robes and with a diadem on her giant head, presided over the driveway of their Brandegee Estate. It reportedly took 12 oxen to haul her into place.

After a century in the open air, Juno was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2011. Getting the statue inside the museum required lifting it by crane and lowering it 80 feet through a skylight. Unfortunately, all those years of exposure in the outdoors had deteriorated her porous marble, with cracks and vandalism further marring the stone, so extensive conservation was carried out right in the gallery (including a nose and lip replacement). Now she’s standing proudly on a steel-reinforced pedestal as the largest classical marble statue in an American museum.

3. LONDON BRIDGE

Block by block, this 19th-century bridge was relocated to a brand new 20th-century American development. Industrialist Robert P. McCulloch bought the 1830s London Bridge from the Corporation of London on April 18, 1968 for close to $2.5 million. The arch bridge—a project of Scottish civil engineer John Rennie completed by his sons, John Rennie the Younger and George—had spanned the River Thames, but was unable to support modern traffic and needed to be replaced. McCulloch had its carefully numbered granite blocks reconstructed over a reinforced concrete structure in Lake Havasu City, a planned community he established in the Arizona desert. (He thought the historic structure would drive tourism and encourage home buyers to invest.) It opened in 1971, connecting a Colorado River island with Lake Havasu City. His plan seems to have worked: Today the town is thriving, and the bridge still draws plenty of tourists.

4. AN IMPERIAL COFFIN

In 2010, an imperial coffin dating to the Tang Dynasty was repatriated to China from the United States. It had gone missing in 2006, stolen right from the tomb of empress Wu Huifei—a staggering feat, since it weighs 27 tons and stretches 13 feet long by 6.5 feet high. After two years of investigations, the local police discovered that the tomb—carved with animals, flowers, and human figures—had been sold to a businessman for $1 million and had traveled all the way to the United States. Once confronted by police via mediators, the businessman agreed to return the item, which then went on display at the Shaanxi History Museum in Xi’an. The incident is a reminder of the ongoing looting of Chinese antiquities from archaeological sites, which experts say is growing increasingly bold.

5. GOD OF A LOST CITY

For 1000 years, Hapy, the god of fertility, was submerged off the Egyptian coast. Then, in the early 2000s, a team of divers discovered a fragment of the colossal 4th-century BCE red granite statue. Weighing 6 tons and standing over 17 feet tall, Hapy is now one of more than 200 objects touring in "Sunken Cities: Egypt's Lost Worlds." From small coins and lamps to an over-12,000-pound sculpture of a king, each is a relic of the drowned city of Thonis-Heracleion. The major Egyptian port was founded around the 7th century BCE, and likely abandoned due to rising sea levels and earthquakes. Hapy is among the most massive of the exhibition’s artifacts, which have toured London, Paris, Zurich, and Saint Louis—with a visit to Minneapolis on the horizon this fall.

6. PIECES OF THE BERLIN WALL

After the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, remnants of the monumental barrier scattered throughout the world. Concrete pieces of the structure stand at almost 100 sites, ranging from a men's bathroom in a Las Vegas casino to the Vatican Gardens in Vatican City. A 12-foot-tall section, gifted to Olympian Usain Bolt, is at Up-Park Camp in Kingston, Jamaica, while a dentist in Sosnovka, Poland, acquired 40 segments and arranged them as an art installation. However, the longest stretch is still in Berlin—the East Side Gallery—adorned with nearly a mile of street art, a shadow of the wall’s former 96-mile path.

7. IRAQ TRAUMA BAY FLOOR

A 3000-pound, 7-by-7-foot section of concrete floor is considered the site where the most American lives were both lost and saved during Operation Iraqi Freedom. In 2008, the floor of Trauma Bay II was delicately relocated from Balad Air Base in Iraq to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Springs, Maryland. The scuffed floor, stained with antiseptics, was salvaged when the temporary medical facilities were torn down. Now part of an exhibition on medical personnel in Iraq, the concrete slab recalls the trauma care for the many wounded who were treated on it between 2003 and 2007.

8. CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLES

The oldest human-made outdoor object in New York City was carved when Manhattan was still wilderness. The 69-foot, 220-ton obelisk, nicknamed Cleopatra’s Needle (though it has no connection to Cleopatra), is located in Central Park just behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Its companion obelisk is by the River Thames in London; both were commissioned around 1450 BCE by Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III for the Heliopolis sun temple. In 12 BCE, they were moved over 100 miles to Alexandria by order of Augustus Caesar, and erected at the Caesareum.

When one was gifted to England, and the other to the United States, in the 19th century, they were lugged aboard ships for sea voyages. The London obelisk was almost lost in a storm that claimed six lives, but the New York obelisk was less disastrous, if no less arduous: It took 32 horses, several months, and a special rail track to get it into place. Following an October 2, 1880 Masonic ceremony, during which a cornerstone was placed in the obelisk, it was officially dedicated on February 22, 1881.