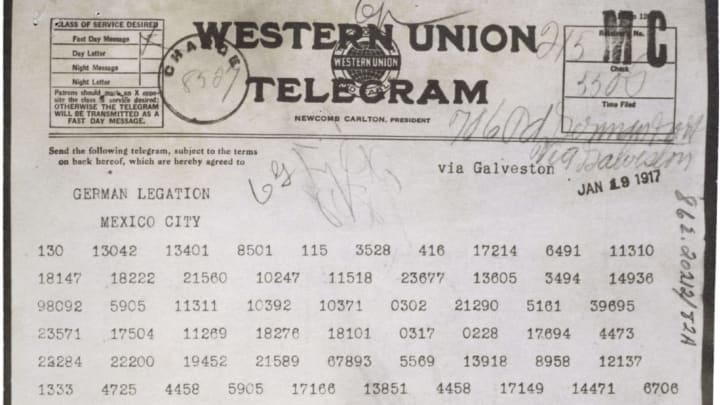

On January 16, 1917, Nigel de Grey, a cryptologist working for the British military, intercepted a coded German telegram sent via standard diplomatic channels. This alone was nothing special. The British cryptanalytic office where de Grey worked, called Room 40, had cracked a handful of Germany's ciphers and intercepted their messages daily. Today, however, was different: The jumble of numbers revealed a political bombshell.

We intend to begin on the 1st of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

The coded message, sent by the German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann, was destined for the German Minister in Mexico City. (Along the way, it had passed through Germany's ambassador in Washington, D.C., Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff.) At the time, America was not involved in the Great War. In fact, President Woodrow Wilson had just secured a second term by riding the slogans "He Kept Us Out of War" and "American First." The decrypted message plainly indicated that Germany was hoping Wilson would stick to his campaign trail talking points.

But the message also showed that Germany was afraid. An escalation of submarine warfare could provoke the United States, compelling it to abandon its isolationist policies and enter the war. If that happened, Germany hoped to distract the U.S. by forcing American troops to focus on an enemy closer to home: Mexico.

Upon realizing the message's significance, de Grey immediately sprinted to the office of his superior, William Reginald "Blinker" Hall.

"Do you want America in the war, Sir?" he shouted.

Hall gave de Grey, who was gleaming with sweat, an incredulous look. "Yes, why?"

"I've got a telegram that will bring them in if you give it to them."

According to an exhibit at the National Cryptologic Museum in Fort Meade, Maryland, "[The British] realized that they held a cryptanalytic 'trump card' that virtually guaranteed America's entry into WWI on the Allied side." Historian David Kahn put it thusly: The "codebreakers held history in the palm of their hands."

When a select few in the U.S. federal government were finally notified of the secret message, many doubted its authenticity, believing it was just a deceitful ploy by the British to win American support. The British assuaged those doubts by acquiring a fresh copy of the coded telegram and handing it over to the Americans. On February 23, a U.S. diplomat saw the message be decrypted with his own eyes—again with the help of codebreaker Nigel de Grey—and independently verified Germany's intentions. The diplomat immediately contacted President Wilson.

When Wilson saw it, he was shocked and insulted. "Good Lord! Good Lord!" he shouted. About one week later, he leaked the message to the press. Americans were similarly outraged.

(As for Mexico, the country knew it was getting a raw deal and never took Germany's bait. Reclaiming the American southwest—what was formerly Mexican territory before the Mexican-American War in the 1840s—was a recipe for disaster. Besides, Germany would have never been able to help anyway: They were blocked by the British Navy.)

By early April, the secret code had compelled the U.S. to join Britain and its allies. Today, the work of de Grey and the other Room 40 codebreakers is widely considered one of the most consequential events in cryptologic history.

Hungry for more details about the Zimmermann telegram? Mental Floss’s coverage of the World War I Centennial has you covered here and here.