A mere 3 percent of the American Museum of Natural History’s 33 million specimens and artifacts are on view at the New York City institution. We took a peek at the rest, which live behind doors locked to the public. From ultra-rare books to ancient bugs, here’s some of the cool stuff we found.

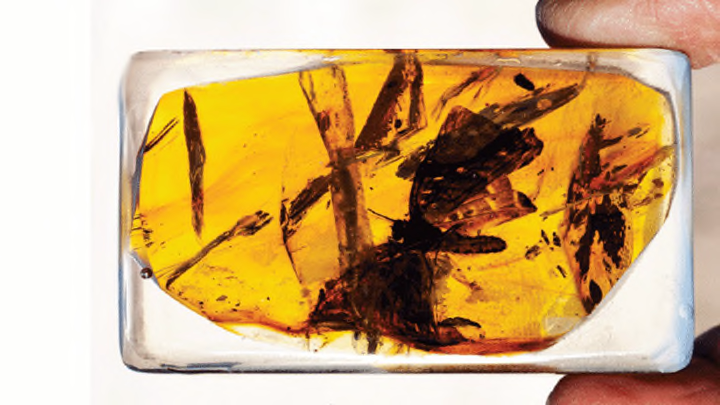

1. A 20-million-year-old butterfly

Preserved in Dominican amber (and a block of epoxy), this Voltinia dramba butterfly is 20 million years old. “Butterflies are rare as fossils,” says David Grimaldi, a curator in the invertebrate zoology division. “They tend to live in areas that wouldn’t fossilize. The other reason is that butterflies’ wings are scaly and soft, and if they’re caught in resin, the scales will come off before the wings actually get covered.”

2. Insects in amber

The museum’s amber collection is housed in Grimaldi’s office. While not huge, “it is dense,” he says. It’s arranged according to deposit and then by group—plants, insects, arthropods, arachnids. (The drawer pictured contains ants.) The only amber on exhibit is in the mineral hall; the pieces with insects in them don’t go on exhibit for conservation reasons—they have to be kept dark and in controlled temperatures and humidity.

3. The rare-book room

We can’t talk about the procedures necessary to enter AMNH’s rare-book room, but we can say that they wouldn’t seem out of place in a Mission: Impossible movie. Like many other behind-the-scenes areas of the museum, the room is climate- and humidity-controlled, and lights are usually dimmed. Age and rarity are two things that factor into a decision to place a book into rare folios, says Thomas Baione, Harold Boeschenstein director of the department of library services.

4. Watercolor fish

Stored in this room are 48 one-of-a-kind watercolors of fish by artist William Belanske, made during three expeditions to the Galapagos on a yacht belonging to William K. Vanderbilt (yes, of those Vanderbilts). Created in the late ’20s, the elaborate miniature illustrations—some as tiny as 7 centimeters—were put into a book privately published by Vanderbilt. This original watercolor of this silver hatchet fish (Argyropelecus lychus Garman) notes that the fish was “taken in dredge, 50 miles S.W. of Cape Mala, Panama, Pacific Ocean, 300 fathoms below the surface” on March 16, 1926.

5. A very large gem

This giant gem—a 21,000 carat light blue topaz called the Brazilian Princess—was cut in the late 1970s, just to prove it could be done, according to George Harlow, curator of the division of physical sciences. “It was the largest gem ever fashioned,” he says. “In order to cut a stone, you have to be able to hold it and put it on a grinding wheel to polish it. That was the challenge at the time.” Machinery had to be created to do the work. Since then, bigger gems have been cut, mostly out of smokey quartz, so it’s no longer the record holder. But it’s so huge that “we had a plan that when the Statue of Liberty had its centennial, a jewelry designer was going to come up with a ring mount to go on the [statue’s] finger,” Harlow says.

6. A 1000-year-old frog

Discovered by a museum team in 1897 in Pueblo Bonito— one of the largest ancestral Pueblo settlements in New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon—this jet and turquoise frog is roughly 1000 years old. Shortly after its discovery, the frog disappeared. An AMNH coordinator found it at a trading post 50 miles north, purchased it, and returned it to the museum. Looting at Chaco Canyon inspired the Antiquities Act of 1906, signed by President Theodore Roosevelt, which protected the site and others like it. Part of the archaeology collection, the frog—which symbolized water for the ancestral Pueblo people—is not on display because “at the moment, we don’t have a Hall of SouthWestern American Indians,” says Paul Beelitz, Director of Collections and Archives - Anthropology.

7. A Tasmanian tiger

Though it went by a number of names—including Tasmanian tiger, zebra dog, and pouched wolf, among others—Thylacinus cynocephalus was actually a marsupial. This animal (one of 12 thylacine specimens in AMNH’s collection) lived at the Bronx Zoo. After it died in 1920, it was given to the museum and mounted. Neil Duncan, Collections Manager of Mammalogy, says he believes this oft-photographed specimen will be “the iconic piece of the department.” Like a human’s fingerprints, each thylacine’s stripes were unique to that individual. The species is now considered extinct; the last of its kind died in an Australian zoo in 1936.

8. A great auk Mount

Before it became extinct, the flightless great auk lived in the North Atlantic, on low-lying islands off Newfoundland and Iceland. “The word penguin originally applied to this bird,” says Paul Sweet, a collections manager. “Its scientific name is Pinguinus. When sailors went down to the Southern Hemisphere, they saw birds that looked superficially like [great auks], and they called them penguins.” The last two auks were killed in 1844; approximately 60 specimens remain—including this one, the Bonaparte auk, which at one point belonged to Napoleon’s nephew, Lucien, an ornithologist.

9. A giant squid beak

In 1998, the museum acquired a male giant squid specimen, which had been accidentally caught by fisherman off the coast of New Zealand. The 25-foot-long animal is stored in a giant steel tank in the museum’s invertebrates department. But its beak is in a different place: the office of Neil H. Landman, curator of the division of paleontology, where it sits in a jar filled with alcohol to keep it from becoming brittle. “It doesn’t really need to be in a jar this big,” says Susan Klofak, a senior museum technician, “but we did need a jar that was this wide-mouthed.”

Here's a video we shot while we were at the museum!

Mental Floss and The American Museum of Natural History from Joshua Scott Photo NYC on Vimeo.

Photos by Joshua Scott.