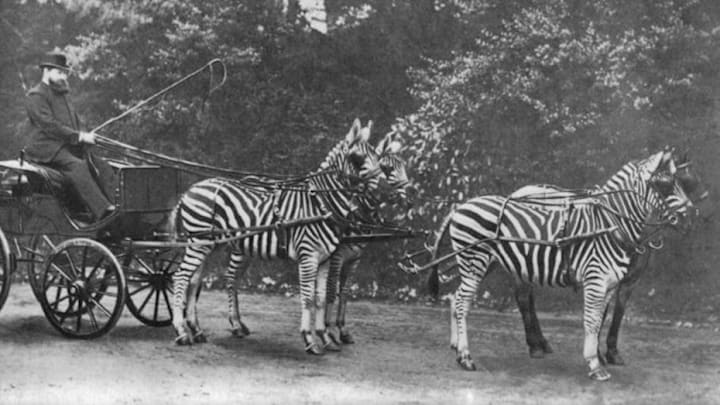

The Victorians loved to keep pets—but they were often not content to make do with an ordinary cat or dog, and preferred something a little more exotic. The artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti kept a wombat; collector Walter Rothschild had a tamed zebra; and Charles Dickens famously featured a fictionalized version of his pet raven, Grip, in his novel Barnaby Rudge. This love for unusual pets is reflected in the many 19th and early 20th century manuals on pet ownership, which offer plenty of helpful (and not-so-helpful) advice on the favored pets of the day. The manuals make for amusing reading—although we don't recommend trying any of this at home.

1. Squirrels

Wild squirrels were frequently caught and kept as pets in Victorian times. As C. Pridham remarked in Domestic Pets: Their Habits and Treatments (1893), “It does seem strange that such a shy, wild-wood creature should ever submit to be made a pet; still more that it should quickly become so very much at home as one generally finds pet squirrels are, with such fond, winning, playful ways of their own that we cannot choose but to give them the petting in which they take such delight.”

Pet squirrels didn't come from pet shops; the manuals suggested that you catch them yourself, preferably as babies, since the young were easier to tame. If climbing up the nearest tree and extracting a wriggling, biting baby squirrel seemed a little too challenging, it was suggested you turn to an obliging gamekeeper. If they had to turn to outside help, buyers were warned not to accept a “dopey” squirrel, as it was likely hopped up on laudanum and would probably soon expire.

Jane Loudon, writing in Domestic Pets: Their Habits and Management (1851) noted that squirrels were best kept "in little ornamental kennels, with a platform for the squirrel to sit on, and a little chain to fasten to a collar round the squirrel’s neck.” But pet squirrels were also sometimes allowed to roam free in the house, making use of the furnishings: “[The squirrel] will run up a window curtain, and along the cornice at the top with wonderful grace and agility; it will also run round the cornice of a room, and if it is richly carved, it will peep out between the leaves and flowers in a very amusing manner.”

G. P. Fermor, in Home Pets Furred and Feathered (1902), chided squirrel owners who did not adequately house their pet: “The harmless, festive little squirrel has, in its wild state, about as joyous a life as any other creature in the world, and it is a matter of wonder that any one who really cared for such a pet could have evolved the painfully cramped cages, with that miserable attempt at a playground, the maddening little wheel.” Instead, he advised that squirrels are happiest with a mate and a large cage with bare branches for them to scamper around. A box filled with moss, dry leaves or hay was recommended to serve as a nest, while bread, milk, nuts, and sugar were said to be the best diet.

2. Badgers

The quaint Eurasian badger of Wind in the Willows fame does not have the vicious reputation of the North American badger, so it is perhaps unsurprising that the Victorians attempted to tame them (the two are actually different species). In Pets and How to Keep Them (1907), Frank Finn says of the badger, “[It] is a very interesting pet with many quaint and curious habits, remarkably like those of a bear on a small scale.”

The problem, Finn noted, comes with finding a secure place to keep the badger, as they are such good diggers they can burrow out of almost any enclosure. To prevent this, the author recommends installing a cement floor and high wire fences. The author also advocates feeding badgers on dog food, but supplementing this with dried fruit and the odd treat of a “wasp’s nest full of larvae."

3. Owls

Although they're not an obvious choice for a furry companion, the Reverend J. G. Wood claimed in his book Our Domestic Pets (1871) that “There are worse pets to be found than owls … by proper management they can be made into very companionable birds, quaint, grotesque, and affectionate withal.”

But then comes the rub: “The chief drawback to the owl as a pet is its nocturnal habits.” That said, the reverend provides a tactic to get around this wrinkle: “Now, although at first to wake the owl will be found rather a tedious business, and to keep it awake still more difficult, a present of a mouse, or a small bird, or a large beetle, will generally rouse it, and cause it to remain awake for some little time.”

4. Ravens

By the Victorian era, ravens were becoming rare in the wild in Britain, in part because so many of these intelligent birds had been captured as pets. Pridham revealed that if found in the wild, ravens could be taken from the nest as fledglings, but that due to their scarcity they were more easily bought at market. He advised raven-keepers to select the largest cage they could find, or else tame them sufficiently that the bird chooses to stay in one's garden, where they “make themselves very useful by clearing the plants of slugs.”

Taming ravens, however, was no simple matter: Reverend Wood wrote that his own family had "been for some months undecided whether we shall have a raven or not. We should greatly like to possess one of these birds, but then we know he would pull up all our newly-sown seeds, get into the milk-pail, tear our papers to pieces, and, in short, spoil everything within his reach.”

5. Jackdaws

Jackdaws, a smaller and more readily available member of the crow family, became a popular alternative to ravens. “To procure a raven, an order to a dealer is almost necessary; but every boy should be ashamed if he cannot catch a young Jackdaw for himself,” Reverend Wood wrote.

Like ravens, jackdaws could be taught to do tricks and learn words, but as the reverend points out, this did have its limits: “Jackdaws are very easily tamed, and become very talkative after their fashion. Their vocabulary is, however, limited, and is mostly restricted to the word 'Jack,' which is uttered on every imaginable occasion.” The 1883 tome Every Day Home Advice Relating Chiefly to Household Management noted that jackdaws, like other talking birds, were subject to various diseases, but that "a rusty nail in their water ... stick-licorice, chalk, or scraped root of white hellebore" could be helpful.

6. Monkeys

Monkeys were considered fashionable pets during Victorian times. Notes on Pet Monkeys and How to Manage Them by Arthur Patterson (1888) includes tips on choosing a suitably simian name, recommending “Bully, Peggy, Mike, Peter, Jacko, Jimmy, Demon, Barney, Tommy, Dulcimer, Uncle or Knips.” However, prospective monkey owners were advised to understand that the creatures weren't exactly easy to manage: “Any one who undertakes to keep one of this family as a pet must be prepared for somewhat unlooked-for developments. Their capacity for mischief and insatiable curiosity are things that have to be reckoned with,” warned M. G. P. Fermor in Home Pets Furred and Feathered.

Fermor recommended that a whole room be set aside for the use of the monkeys: “The furniture of such an apartment need not be expensive—poles, ropes, bars and swings are what the occupants will appreciate more than chairs or sofas.” If just one monkey was to be kept, it could be attached to a light, strong chain, which should be affixed to something it couldn't drag around. But Fermor cautions: “The Larger monkeys cannot be given as much freedom as their smaller brethren, for should one of them embark upon a tour of destruction, or give free rein to his impish wickedness, it would be a serious matter to restore order.”

If all else fails, Patterson recommended the following ploy for gaining your monkey's trust: Let a friend go up to the animal's cage brandishing and swinging a stick in order to frighten the animal. “In the midst of this nonsense, rush forward, and pretend to take the part of your pet, thrash your friend to within an inch of his life with the very stick he has been using, and put him out. Next take the monkey some savory morsel, such as a date, or an apple, and sympathize with it. You are sworn friends from that time.”