Bernarr Macfadden, who almost single-handedly launched the twin American obsessions with diet and exercise, wanted you to picture a roaring lion when you said his name out loud. Not content with his birth name, Bernard, the young Macfadden had his name legally changed so it supposedly better resembled a roar: Bernarr.

Macfadden certainly did roar his way through life. Born August 16, 1868 as Bernard McFadden on a farm in Mill Spring, Missouri, he was orphaned by the time he was 11. Macfadden’s father died from delirium tremens (alcohol withdrawal), and his mother from tuberculosis. The young boy was briefly installed in a Chicago boarding school, then housed, equally briefly, with relatives who ran a hotel in the city. He then worked as a farm laborer in northern Illinois for two years before he took to the open road, working as a miner, a dentist's assistant, a wood chopper, a printer’s apprentice, and a water boy for a construction team.

Because he spent his childhood dreading the arrival of the same tuberculosis symptoms that had killed his mother, Macfadden grew increasingly obsessed with physical fitness and healthy eating as wards against disease. By his late teenage years, he had set himself up in St. Louis, where he diligently practiced a well-honed exercise routine that included repeat sets with dumbbells and the horizontal bar, as well as daily six-mile walks carrying a 10-pound lead bar. He also decided on his purpose in life: spreading the gospel of exercise.

Around 1887, he rented a gym space in St. Louis, Missouri, and set a bold sign out front: "Bernarr Macfadden-Kinistherapist-Teacher of Higher Physical Culture." If you've never heard of a kinistherapist before, neither had Macfadden. The nonexistent profession just sounded good to him. And it sounded good to the people of St. Louis too. In a short while, business was booming.

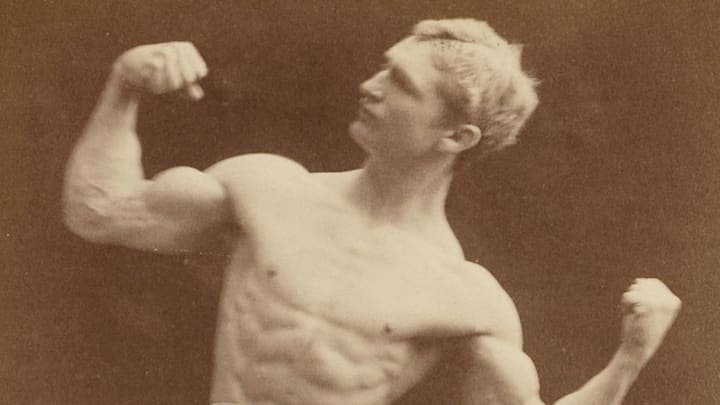

But Macfadden had bigger dreams than St. Louis could fulfill. His drive to spread the gospel of physical culture soon led him to leave behind his St. Louis gym and head for New York City, where he rented a place in Manhattan and invited the press over for a “Physical Culture Matinee.” Surprisingly, the press actually showed up; their entertainment that afternoon consisted of Macfadden “chatting and posing in an interesting way,” according to one observer.

In 1899, at 30 years old, Macfadden launched Physical Culture magazine as a showcase for his ideas on bodybuilding, exercise, and diet. Those ideas boiled down to a simple formula: eat good foods, exercise often, and go on occasional fasts (his focus on fasting is seen as the precursor to today's popular ketogenic diet, by some accounts). However, his enthusiasm often overwhelmed his sensible ideas. He frequently campaigned against doctors and vaccinations, and generalized American “prudery.”

Despite its quirky character, Physical Culture was a near-immediate hit. Macfadden’s tireless promotion and obvious zeal for his ideas were aided by convenient timing: Just as the magazine launched, Americans were turning for the first time en masse to improving their diet and exercise routines, encouraged by a similar craze in Britain as well as nationalistic fitness efforts like the gymnasiums favored by German-American immigrants. Macfadden was in the right place at the right time to be the prophet of the diet and exercise movement.

Like other self-styled prophets before him, however, Macfadden’s outsized personality became one of his greatest obstacles. He was given to fits of mooing and braying, which he believed aided in voice development. He wore his hair thick, wild, and long (at least by early 20th century standards) as proof of the efficacy of his cure for baldness (a “cure,” by the way, that involved vigorous pulling on the hair). He believed shoes were unnatural, so he frequently tramped about barefoot. He slept on the floor, with windows wide open even in winter. His hatred for the fashion industry led him to wear his clothes for years until they were literally hanging from his body in tatters. This last habit led to some unfortunate confrontations with the doormen at his New York apartment building, who frequently mistook him for a hobo.

Nevertheless, Physical Culture magazine made Macfadden wealthy and provided the seed money to launch twin empires in publishing and health. By the 1920s, he owned 10 highly successful magazines and was worth upward of $30 million. His publishing ideas were innovative and profitable, despite their often tawdry character. He launched the first true confession magazine, True Story, in 1919, as well as a number of other magazines in the same vein, such as True Romance and True Detective. He also launched the legendary New York Evening Graphic, one of the forerunners of modern tabloid newspapers. With article titles such as “I Taught My Wife to Drink,” “I Am the Mother of My Sister’s Son,” and “I Killed Him, What’ll I Do?,” the sordid stories of sin, guilt, and redemption in Macfadden's titles were hugely popular with the American masses.

Macfadden simultaneously spread his Physical Culture empire into the health arena as well. He opened a chain of Physical Culture restaurants, with the gimmick of charging one cent for every item on the menu, following the idea that the best foods for you were also the cheapest. He also established four spas, dubbed “healthoriums,” in upstate New York, Long Island, the New Jersey Pine Barrens, and Battle Creek, Michigan. At the Macfadden spas, participants could aim to achieve “an absolute purity of their blood through a regimen of exercise, fresh air, bland diet, and no medicines.” Macfadden’s empire-building reached its zenith at his spa in the New Jersey Pine Barrens, which he vigorously—and unsuccessfully—campaigned to have incorporated into a new town dubbed “Physical Culture City.”

Macfadden’s outsized ego and overbearing convictions reportedly made him a difficult marital partner. His first two marriages quickly ended in divorce. His third marriage, arguably more successful, came about in a particularly Macfadden-ian way: Bernarr was in England, judging a contest he’d organized to find “the most perfectly formed female.” The winner was one Mary Williamson, a competitive swimmer, who was subsequently convinced to become Macfadden's third bride. He later would assert that her prize for winning the contest was … him.

Their marriage survived 34 years and produced seven children, named (by Bernarr, of course): Byrnece, Beulah, Beverly, Braunda, Byrne, Berwyn, and Bruce (although some sources call him Brewster). In 1946, Mary obtained a divorce, in drawn-out and very public proceedings.

Meanwhile, Macfadden’s fortunes began to diminish. The New York Evening Graphic, despite some early success, was quickly derided as one of America’s worst papers—thanks to sleazy headlines like “Weed Parties in Soldiers’ Love Nest.” The newspaper’s gradual collapse drained millions from Macfadden’s bank account. An ill-conceived run for the Republican nominee for president in 1936 also led to widespread public derision for “Body Love Macfadden.” A third blow was the failure of his chain of one-cent restaurants; the gimmick couldn’t withstand the reality of restaurant overhead.

Macfadden was married a fourth time, briefly, to a woman half his age, who shortly after had the marriage annulled. He sold off his remaining magazine interests in the 1940s and spent his last years, and the last of his fortune, on a variety of stunts and schemes. He ran for the U.S. Senate in Florida, offered a prize for the best biographical play about his life, and, when he turned 81, celebrated the accomplishment by parachuting out of an airplane. That feat became an annual event for Macfadden, who proudly defied his advancing years by parachuting into the Hudson River every birthday, and once, when he turned 84, into the Seine in Paris. He said he’d continue every year until he turned 120.

Sadly, he died a few years later, at age 87, in 1955. His cause of death, depending on the source, was either cerebral thrombosis (a blood clot in a cerebral vein in the brain) or an attack of jaundice following a three-day fast. By the time he died, Macfadden had about $50,000 left of his fortune and was generally regarded as an eccentric hovering on the edges of fame, always angling for a new way to see his name in the paper.

Macfadden’s ideas, however, outlived him, and some of them ended up having some merit. He was one of the first Americans to loudly proclaim the benefits of exercise and dieting. He railed against corsets and white bread, both of which have substantially declined in popularity. Today, you can find thousands of people jogging and lifting weights in cities across the country—highly unusual pursuits before Macfadden started spreading the doctrine of Physical Culture.

Additional Source: Great American Eccentrics