On May 25, 1979, 6-year-old Etan Patz lobbied his parents for permission to walk to his school bus stop alone. It was the last day of classes before Memorial Day, and Patz argued that the stop was only two blocks from his family’s Lower Manhattan apartment building. He planned to get a soda at a local deli, he told them, then head straight for the bus. Etan's parents eventually relented, knowing it was a short walk and that their son was a responsible kid.

On September 5, 1982, 12-year-old Johnny Gosch loaded up his newspaper carrier’s bag in Des Moines, Iowa and began making deliveries. He was trailed by his dog, Gretchen.

On August 12, 1984, Eugene Martin performed a similar ritual, heading off on his paper route in the same area of Des Moines. The 13-year-old normally made deliveries with his stepbrother, but had elected to go by himself that morning.

Patz never arrived at school; Gosch and Martin never returned from their delivery shifts. Gosch's dog, Gretchen, came home by herself.

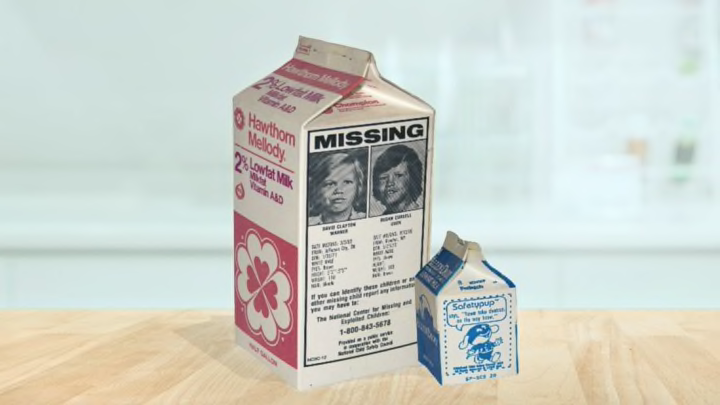

In late 1984 and into the first part of 1985, the images of all three boys helped usher in a peculiar chapter in law enforcement history. They were among the first children to be featured on milk cartons, which asked for the public’s assistance in helping authorities nationwide locate missing kids. Their faces appeared on 3 to 5 billion dairy containers across the country, a concerted effort in a pre-internet era to disseminate information and solicit tips. The press dubbed them “the milk carton kids,” creating an indelible image of missing children in back-and-white photographs on the paper packaging that took up residence at breakfast tables in nearly every state.

As ubiquitous as these photos were, their effectiveness was questionable. It wasn’t long before child activists started to voice concern—not specifically for the abducted children, but for the kids who were receiving messages that strangers were dangerous and that they, too, might one day become a dairy industry-endorsed statistic. Despite law enforcement’s best intentions, the milk carton craze had the unintended consequence of scaring more children than it helped.

In the 1970s, a grassroots effort began to address the issue of noncustodial parents taking their own children without the consent of their legal guardians. Fathers and mothers frustrated over court custody rulings or expressing concern over how a child might be treated by the opposing parent would scoop up their kids and relocate to another state. Police were hesitant to get involved, believing it represented more of a domestic dispute and civil matter than an actual crime. If they did intervene, they often required parents to wait as long as 72 hours before allowing them to file a police report.

A new phrase, “child snatching,” entered the lexicon, and parent groups circulated pamphlets with information on missing children. Even if police were cooperative, the glacial process of faxing information to various police departments meant that a missing child and a rogue parent had plenty of time to disappear somewhere in the country before word ever got out.

That was the state of public notification when Eugene Martin went missing in August 1984. Being the second paperboy in Des Moines to disappear following Johnny Gosch drew attention to both cases. After being approached by the children's parents and the Des Moines police chief, Anderson Erikson Dairy agreed to print photos of both boys on milk cartons in the Des Moines area in September 1984. A second factory, Prairie Farms Dairy, joined them. From there, dairies in Wisconsin, Illinois, and California followed, with Chicago’s launch in January 1985 drawing national media attention. By March of that year, 700 dairies were plastering billions of cartons with the faces of missing kids, even if they were from out of state. Etan Patz, for example, had his face printed on cartons in New Jersey and beyond, as abducted children could often be taken across state lines.

The project fell under the direction of the National Child Safety Council, a Michigan-based nonprofit whose founder, H.R. Wilkinson, had seen the Des Moines campaign and helped with its expansion. The general state of child welfare also received assistance from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a subdivision of the Department of Justice created by then-president Ronald Reagan to help address what was growing into a matter of national concern. But the biggest participant may have been International Paper Company, a factory supplier that made printing plates of the photographs for dairies to use free of charge. (While dairies didn’t have to pay extra, the industry did lose money in the effort, as the photos were using space typically taken by paid advertising.)

While the milk cartons are the most frequently remembered component of the campaign, photos showed up in a variety of places. Utility companies stuffed envelopes with missing-child inserts on the assumption that most everyone needed to open and acknowledge their gas or electric bills. In New York City, hot dog vendors agreed to plaster their stands with missing-child posters. The photos popped up on grocery bags. In schools, single-serving cartons of milk were printed with tips on avoiding strangers courtesy of a mascot named Safetypup.

Initially, the initiative showed potential. In January 1985, a 13-year-old runaway named Doria Paige Yarbrough was watching television with her friends in Fresno, California when a news segment talking about the milk carton campaign came on; Yarbrough’s face was on one of the containers. Struck by what she had done, she returned home to her mother in Lancaster, California. In October 1985, 7-year-old Bonnie Bullock was eating cereal in Salida, Colorado when she looked up and saw her own face on a carton. She told a friend, who told her parents, who phoned police. Bullock had been a noncustodial abduction, taken from her father in Florida by her mother. She was reunited with him shortly thereafter.

While those cases drew national attention, they also made a point of demonstrating the enormous odds of the photos leading to a positive outcome. Neither child had been abducted by a stranger, which had a significantly more substantial chance of ending in tragedy. Nor did people seem to be able to compartmentalize the statistics being thrown around in the media. While a reported 1.5 million children were reported missing each year—a number that originated with the Department of Health and Human Services—only 4000 to 5000 cases were considered actual abductions. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children assisted in over 12,000 cases in two-and-a-half years, but just 393 of those involved kids abducted by strangers.

No one was arguing those cases weren’t deserving of attention, but some reputable critics were arguing that a milk carton might not necessarily be the ideal method for capturing it.

By 1986, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children was reporting that four children had been recovered as a result of their photograph being printed on the cartons, a number that grew to six by 1987. Considering the billions of cartons in circulation, however, that figure seemed only faintly promising.

The problem, as the Center would later admit, was that adults in a position to identify children or contact authorities weren’t paying much attention to the cartons. Most of the observation was done by their kids, who stared at the photos at the breakfast table. Rarely able to recognize anyone they knew, kids instead internalized the fear that they themselves might become victimized. While photos certainly helped—more than 100 children were located due to blanketing communities with their image—putting them on milk containers wasn't having the desired effect.

Renowned pediatrician and author Benjamin Spock spoke out against the campaign, voicing concern that the magnitude of the practice was teaching children about criminal behavior before they had the emotional maturity to deal with it. The American Academy of Pediatrics echoed his statements. The concept of “stranger danger,” which provoked anxiety in parents and kids alike, was statistically out of proportion with the chances a child was going to be abducted. And while tips did come in, they were rarely of any significance to the cases.

“What it did was raise the level of awareness,” Noreen Gosch, Johnny’s mother, told the Associated Press. “It didn’t necessarily bring us tips or leads we could actually use.”

Still, that awareness was crucial. And while the cartons may not have led directly to a child's recovery, it's impossible to measure how the practice may have acted as a preventative measure, discouraging kids from running away or perpetrators from committing an act that would likely bring about national attention.

By 1987, dairies began phasing out the practice, replacing the photographs with safety tips for kids. The increasing popularity of plastic milk jugs may have also hastened the demise of the campaign. By 1989, images of missing children had all but disappeared from breakfast tables. Improved telecommunications in the 1990s and beyond—including internet dispatches and Amber Alerts—made the relatively primitive method of milk carton messages obsolete.

The original “milk carton kids”—Patz, Gosch, and Martin—and their families that helped usher in the milk carton movement never benefited directly from it. Gosch and Martin have never been located and no suspects have ever been arrested. In 2012, a store clerk named Pedro Hernandez who worked in Etan Patz’s neighborhood confessed to his murder after his brother-in-law told police that Hernandez once admitted to being involved. Hernandez was tried and convicted of the crime in 2017, and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

While his face has long since disappeared from all those millions of cartons, Patz’s legacy endures. In 1983, Reagan declared the date of his disappearance, May 25, as National Missing Children’s Day.