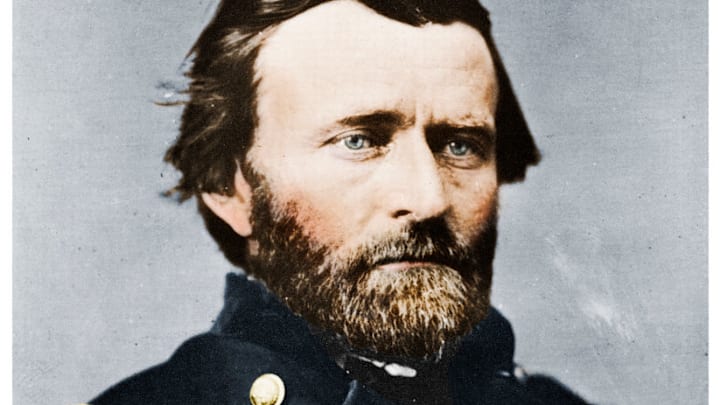

From modest beginnings and Civil War military victories to the United States presidency and tough times in between, Ulysses S. Grant was a complicated man in perhaps the most complicated time in the country’s history. While his legacy has varied over the years, his unmistakable valor and ability to pull himself up by his (inevitably disheveled) bootstraps make him a fascinating figure in American history. Here are a few things you might not have known about the 18th president of the United States.

1. Ulysses S. Grant's real name is Hiram Ulysses Grant.

If you called him Ulysses S. Grant during his youth, he wouldn’t know who you were talking about. Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, to Jesse Root Grant, a tanner, and Hannah Simpson Grant. The young Ulysses did go by his middle name as a boy (according to legend, he disliked the initials H.U.G.), but the moniker known to the history books was bestowed upon him when he was nominated to attend West Point by Ohio congressman Thomas Hamer. Hamer, an old friend of Grant’s father, did Ulysses a favor and nominated him for enrollment at the prestigious military academy in 1839, and somehow, in the process, his name was put down as “Ulysses S. Grant,” with the “S” standing for Grant’s mother’s maiden name: Simpson.

The young Grant, aware of his meager social standing, accepted the clerical error, and the name stuck. His classmates even used it as a nickname, calling him “Sam.” Later, in an 1844 letter to his future wife Julia, he joked, “Find some name beginning with ‘S’ for me, You know I have an ‘S’ in my name and don’t know what it stands for.” (Grant isn’t the only president with a strange middle name, by the way. Harry S. Truman’s middle initial was also just an “S.”)

2. Ulysses S. Grant hated the West Point uniform.

Though Grant’s father hoped that pushing him into the prestige of West Point would open up opportunities for his son, the younger Grant pretty much hated the decorum of going to school. He was known to be generally unkempt during his time there, and received demerits for his sloppy uniform habits (something he’d continue during his time as commander of the Union Army during the Civil War).

In an 1839 letter, a 17-year-old Grant told his cousin, McKinstry Griffith, he “would laugh at my appearance” if he saw the cadet in his uniform: “My pants set as tight to my skin as the bark to a tree.” If he bent over, he wrote, “they are very apt to crack with a report as loud as a pistol,” and “If you were to see me at a distance, the first question you would ask would be ‘Is that a fish or an animal?’”

3. Ulysses S. Grant was introduced to his wife, Julia, by her brother.

Julia Boggs Dent was born January 26, 1826 in St. Louis. She was a voracious reader and skilled pianist who also had some artistic talent.

Julia was introduced to her future husband by her brother, Fred, who attended West Point alongside the future general. He wrote to his sister of Grant, “I want you to know him, he is pure gold.” The matchmaker mentioned Julia to Grant as well. After graduating from West Point in 1843 as a brevet second lieutenant, Grant began to visit the Dents at their home outside St. Louis in 1844, and popped the question to Julia a few months later. They hid their engagement until 1845, when Grant asked her father for her hand; though Mr. Dent said yes, the Mexican-American War broke out, and Julia and Grant didn't marry until 1848.

4. Ulysses S. Grant went into battle with another future U.S. president: Zachary Taylor.

Grant fought in the Mexican-American War under General Zachary “Old Rough and Ready” Taylor, who went on to become the 12th president of the United States in 1849.

Taylor led Grant in his first military battle, along with thousands of troops, at the Battle of Palo Alto, with Grant going on to fight in nearly every major battle of the war. As regimental quartermaster during the Battle of Monterrey, Grant rode through heavy Mexican gunfire to deliver a message for much-needed ammunition after Taylor’s troops ran out of bullets.

In his memoirs, Grant recalled how he admired Taylor for the same traits that he would be known for, including how Taylor “knew how to express what he wanted to say in the fewest well-chosen words” and how his general’s style “[met] the emergency without reference to how they would read in history.”

5. Ulysses S. Grant wasn't a military man at the start of the Civil War.

The war hero of the Mexican-American conflict was far from those accolades when the Civil War broke out in 1861. After his resignation, Grant took to a series of civilian jobs without much success. He spent seven years as a farmer, real estate agent, and rent collector, and he even sold firewood on St. Louis street corners. When the Civil War was announced, Grant was working in his father’s leather store in Galena, Illinois.

6. Ulysses S. Grant turned his occupational failure into military success.

With a newfound patriotism at the outbreak of war, Grant attempted to enlist, but was initially rejected for a military appointment due to his previous indiscretions.

Illinois congressman Elihu Washburne took a chance on Grant and arranged a meeting with the governor of Illinois, Richard Yates. Grant was appointed to command a volunteer regiment, whipping them into shape well enough that it eventually earned Grant a spot as brigadier general of volunteers. (Grant later reciprocated Washburne’s favor by appointing Washburne to U.S. secretary of state, and later minister to France.)

Grant is credited with commanding two significant early Union victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, which earned him the nickname "Unconditional Surrender Grant."

7. Ulysses S. Grant almost lost his post at Shiloh.

After the dual victories of Henry and Donelson, Grant faced harsh criticism for his leadership during the Battle of Shiloh, one of the costliest battles in American history to that point. Though the Union came out victorious, both sides suffered a staggering 23,746 total casualties—a majority of which were Union soldiers.

On April 6, 1862, Grant’s army was waiting to rendezvous with troops led by General Don Carlos Buell, with the goal of overtaking a major Confederate railroad junction and strategic transportation link in nearby Corinth, Mississippi. But before Buell arrived, Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston’s forces attacked Grant's troops. Caught off guard, the Union soldiers spent most of that day being beaten back by Confederate forces, to the point of being nearly overrun until Buell’s army showed up to provide reinforcements.

The Union won, but Grant’s lack of preparedness immediately brought about demands for his removal.

Pennsylvania politician Alexander McClure visited President Abraham Lincoln at the White House to call for Grant’s removal, saying, “I appealed to Lincoln for his own sake to remove Grant at once, and, in giving my reasons for it, I simply voiced the admittedly overwhelming protest from the loyal people of the land against Grant’s continuance in command.” McClure later recalled that Lincoln responded, “I can’t spare this man; he fights.”

Despite rumors that his early blunder at Shiloh was because he was under the influence, Grant assured Julia in a letter, dated April 30, 1862, that he was “sober as a deacon no matter what is said to the contrary.”

8. Ulysses S. Grant's next few battles, including Vicksburg and Chattanooga, solidified his bona fides.

For his next major objective, Grant commandeered a six-week siege on the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in order to take the city over from General John C. Pemberton. The Union bombardment was so profound that most residents of the city were forced to leave their homes and shack up in caves. The editor of the town’s Daily Citizen newspaper was even reduced to printing the news on wallpaper. Pemberton eventually surrendered on July 4, 1863.

Later that year, from November 23 to November 25, Union forces routed the Confederates at the Battle of Chattanooga. Grant, then a major general, masterminded a three-part attack—one of which was led by Major General William Tecumseh Sherman—against enemy entrenchments on two Confederate strongholds: Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain. The multi-faceted gamble worked, and the Union army was victorious.

Because of Grant’s successes, in March 1864 he was promoted to lieutenant general with command of all Union forces. From then on, Grant would answer only to the president.

9. Ulysses S. Grant wrote the surrender terms at Appomattox.

Despite one last push by General Robert E. Lee to rally his beleaguered troops, the Battle of Appomattox Court House lasted only a few hours after Confederate forces were cut off from their final provisions and support. Lee sent a message to Grant announcing he was willing to surrender, and the two generals eventually met in the front parlor of the Wilmer McLean home in the early afternoon of April 9, 1865.

Lee arrived in full military dress—complete with sash and sword—while Grant characteristically stuck with his well-worn and muddied field uniform and boots. He then wrote out the single-paragraph terms of surrender.

Under the terms, Confederate soldiers and officers were allowed to return home; officers were permitted to keep their horses for use as farm animals (according to the National Park Service, Grant also ordered officers to allow private soldiers to keep their animals) and to keep side arms. Grant allowed starving Confederate troops be fed with Union rations.

When news of the surrender reached nearby Union troops, gun salutes rang out, but Grant, aware of the weight of the bloody war, sent out an order for all celebrations to stop. “The war is over,” he said. “The rebels are our countrymen again; and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field.”

10. Ulysses S. Grant was supposed to be at Ford's Theatre the night Abraham Lincoln was shot.

Days after the Appomattox surrender, Lincoln invited Grant to see a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. Advertisements for the Good Friday 1865 performance even boasted that Grant would accompany President Lincoln and the first lady.

The celebrated general backed out, explaining that he and Julia were to travel to New Jersey to see their children instead. (In reality, Julia despised Mary Todd Lincoln and didn’t want to be in her company. Grant didn’t particularly want to go anyway. )

Grant was supposedly a target of John Wilkes Booth’s assassination plot, and was to be taken out along with Lincoln that night.

11. Ulysses S. Grant had no political experience when he became president.

Though he was a war hero, and sat in on cabinet meetings during Reconstruction under President Andrew Johnson, Grant had no political experience to speak of when he was nominated for president in 1868. But because the Civil War still loomed large at the time, it makes sense that one of the people credited with keeping the U.S. together would be given a shot.

He was elected for a second term, but scandals—including the 1869 Black Friday incident where two financiers attempted to corner the country’s gold market while Grant’s Treasury Department sold gold at weekly intervals to pay off the national debt—and his inability to maneuver party politics plagued his terms in office.

“It was my fortune, or misfortune, to be called to the office of Chief Executive without any previous political training,” he wrote in his farewell message to Congress. “Under such circumstances it is but reasonable to suppose that errors of judgment must have occurred.”

12. Ulysses S. Grant had some bad luck after his presidency.

Despite the unofficial two-term rule in use since George Washington—the 22nd Amendment, establishing an official presidential term limit, was ratified in 1951—Grant attempted a third term four years after leaving office, but couldn’t get enough votes at the Republican convention. James Garfield won the nomination and eventually the presidency.

After retiring from politics, Grant invested his savings and became a partner in a financial firm where his son was also a partner. But it eventually went bankrupt in 1884 after another of the partners swindled investors with faulty loans.

His luck didn’t seem to get any better—soon after, he learned he had throat cancer. To pay off his mounting debts and to provide for his family after he was gone, Grant began writing his memoirs and eventually signed a contract with none other than Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn author Mark Twain, whose Charles L. Webster & Company publishing house needed a hit.

13. Ulysses S. Grant died on July 23, 1885.

Grant finished his book just before he died; the two-volume Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant was a critical and commercial success, earning Julia royalties of about $450,000 (or more than $10 million today).

Grant's final resting place is a 150-foot-high tomb in New York City. According to the NPS, the tomb, designed by John Duncan, is the largest mausoleum in North America. The outside reads, “Let us have peace.” Julia was laid to rest next to her husband after her death in 1902.

This article was originally published in 2019; it has been updated for 2022.