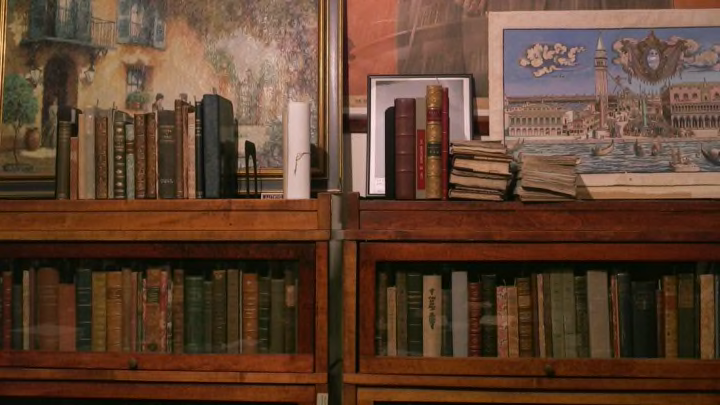

Tucked away in the middle of a drab street in Midtown Manhattan, the Conjuring Arts Research Center holds more than 15,000 books, magazines, and artifacts related to magic and its allied arts, whether that means psychic phenomena, hypnosis, ventriloquism, or men who claim to vomit wine. Inside, posters and banners for Houdini and Alexander ("The Man Who Knows") compete with row after row of centuries-old books. Mental Floss visited recently and spoke to Executive Director William Kalush, who showed us some of the most interesting items the library has to offer.

1. HANDCUFFS OWNED BY HOUDINI

These iron handcuffs were once part of Houdini's collection. They are reputed to have held Charles Guiteau, the assassin of President Garfield, when he was hanged in 1882. Kalush is skeptical about that provenance, but says Houdini thought it was at least possible. (Houdini and Guiteau had a special connection: In 1906, the magician escaped from the Washington, D.C. jail that held Guiteau while he was awaiting execution.)

2. JOSEPH PINETTI BROADSIDE

One of the most celebrated magicians of the late 18th century, Joseph Pinetti was a former professor who sometimes presented his tricks as scientific experiments. Originally from Rome, he traveled all over Europe performing in flamboyant settings (he favored chandeliers and multiple changes of clothes), becoming particularly famous in Russia and France. This German broadside is from 1781, and Kalush says it's probably the earliest known broadside on the magician.

3. OPERA-NOVA

This unique Venetian pamphlet contains simple explanations of magic tricks, and would have once been sold door-to-door by a pamphleteer. Probably from around 1530, it's just one sheet of paper printed on both sides and folded twice, making eight little pages. "It's extremely rare to find examples of these kinds of pamphlets—they're almost never found in more than one example," Kalush says.

4. HOCUS POCUS JUNIOR: THE ANATOMY OF LEGERDEMAIN

This is an in-depth manual for magic originally written in 1634; the Conjuring Arts copy was printed about 20 years later. The title "Hocus Pocus Junior" is a reference to a famous early 17th-century performer named William Vincent, who used the stage name Hocus Pocus. "It's really just a play on words, like saying I'm the junior to his senior. William Vincent never wrote anything," Kalush explains. "But it's a wonderful book in English that's really a manual of how to do things. As opposed to the little pamphlet from Italy, it has really solid descriptions on methods. You could become a great magician just by reading Hocus Pocus Junior."

5. DECRETALS OF POPE BONIFACE VIII

This 13th-century book of canon law (church law) included the decretals, or papal pronouncements, of Pope Boniface VIII—including laws against magic tricks. Though it was rare for such books to have illustrations, this one, printed in Venice in 1514, includes an image of a priest or monk doing the cups and balls trick. "The penalty [for doing magic tricks] was to lose your privileges and to be treated 'no better than a buffoon,'" Kalush says. "And the only other illustrated edition we've seen is from 1525, when the priest [performing cups and balls] has been demoted to buffoon, and is wearing a court jester-type outfit."

According to Kalush, Boniface VIII was particularly concerned about magic tricks because he'd used them to help secure the papacy, whispering the "word of God" through a long tube into his predecessor's ear to convince him to retire.

6. GIROLAMO SCOTTO MEDAL

Girolamo Scotto was an Italian entertainer, magician, and alchemist active in the last half of the 16th century who is said to have performed magic for Queen Elizabeth I, among other notables. This lead medal was produced from a wax sculpture by the famed Milanese sculptor Antonio Abondio toward the end of the 16th century. "In those days there were no such things as business cards, so he had this medal made," Kalush says. It was originally cast in various other metals too, including silver, bronze, and gold.

7. IL LABERINTO

This "mind-reading" book, printed in Venice in 1607, served as a prop for a trick in which the magician was able to guess an image chosen by the viewer and held in their mind (much like the familiar card trick). Another item the library holds—A Devotione Del Signore from Naples, 1617—is similar but uses religious iconography. "We suspect they used religious iconography because Naples was under Spanish rule, and closer to the Inquisition, than was Venice at that time," Kalush explains.

8. PICTAGORAS ARITHMETRICE INTRODUCTOR

Printed in 1491 in Florence, this work by mathematician Filippo Calandri was one of the first arithmetic books in the Italian language. As a treat, there were magic tricks in the back. "After you learned your arithmetic lessons, you were able to use those pages to do a little bit of mind-reading," Kalush says.

9. DIALOGO DI PIETRO ARETINO NEL QVALE SI PARLA DEL GIOCO CON MORALITA PIACEVOLE ("LE CARTE PARLANTI")

This 1543 text, written by the noted satirist Pietro Aretino, is a dialogue between a deck of cards and a man who makes them. Meant simply as entertainment, "it talks about people who cheat, like a Spanish cheater who had a machine in his sleeve who would exchange good cards for bad cards, and other comments about card magic from the playing cards’ perspective," Kalush explains.

10. THE DISCOVERIE OF WITCHCRAFT

In 1584, a British justice of the peace named Reginald Scot published The discoverie of witchcraft, which argued that much of what appeared to be magic could be explained by sociological or psychological reasoning—or by simple sleight of hand. "It's not secular; he's not saying he doesn't believe it exists," Kalush says. "It's just that a lot of things that were being attributed to witchcraft are not." For example, Scot said that the guilt produced by those who denied funds to impoverished women may have led them to accuse those same women of dark, magical works. It's also the first important book of sleight of hand, according to Kalush, with substantial sections on coin magic, card magic, and other techniques that were popular at the time.

11. FALACIE OF THE GREAT WATER-DRINKER DISCOVERED

This pamphlet from 1650 is about Floram Marchand, a man who would swallow gallons of water and then regurgitate it into a fountain, sometimes in multiple colors (he claimed it was wine, but in fact it was water dyed red with a Brazil nut solution). "It's quite interesting because it was written by Peedle and Cozbie [two English entrepreneurs], who learned the secret from the master, and as a thank-you they exposed the trick and published it," Kalush says.

12. EXPERT PLAYING CARDS

The Conjuring Arts Research Center, a non-profit, also runs the Expert Playing Card Company, devoted to producing high-quality playing cards. All proceeds benefit the 501(c)3. "Expert has produced hundreds of different custom-printed decks for many artists and magicians all over the world," Kalush says; recent examples include decks inspired by Greek mythology, Art Nouveau, Gothic architecture, and classical music.

13. GIBECIERE

The center has also been publishing their own scholarly journal, Gibeciere, since 2005. Its pages cover little-known details about famous historical magicians, tricks, devices, and manuscripts, with work from Spanish, Italian, French, German, and other languages translated in-house. "Many of the great magic historians have contributed," Kalush says. The journal is edited by Stephen Minch, who ran an "important magic publishing house for years that published some of the great books on magic."

The name Gibeciere is a reference to a type of bag medieval hunters would wear around their waists, later appropriated by magicians as a convenient place to keep their props. Minch choose the title, Kalush says, "since we hoped it would be a mixed bag of research and history."

All photos by Anna Green.