The Surprising Origin of the Word ‘Morgue’

A verb describing the act of gazing upon the dead—originating in a grim Parisian prison—likely led to the French term ‘morgue.’

Today, the word morgue conjures up images of an efficient, hygienic room overseen by professionals in lab coats and rubber gloves. Most of us are familiar with its inner workings only from cop shows and crime novels, never having had the desire—or need—to visit one in real life. But our image of the modern, sterile morgue stands in stark contrast with the room that originally gave rise to the term.

Early Definitions of the Morgue

In 18th century Paris, visitors to the Grand Châtelet—a combined court, police headquarters, and prison that served as the seat of common-law jurisdiction in pre-revolutionary France—could descend to the basse-geôle (basement jail) and peer in through the grille of the door. There, they would catch a glimpse of a small room where unidentified dead bodies were displayed to the public, strewn across the bare floor.

The room became informally known as la morgue, an early definition of which appears in the 1718 Dictionnaire de l’Académie: “A place at the Châtelet, where dead bodies that have been found are open to the public view, in order that they be recognized.”

The name for this gruesome room likely had its roots in the Archaic French verb morguer, which means “to look solemnly.” Historians think that such rooms had existed in Parisian prisons since the 14th century, initially as a place where newly incarcerated prisoners would be held until identified, but later to deal with the many dead bodies found on the streets or pulled from the Seine. (In fact, there were so many bodies in the river that a huge net was stretched across the river at St. Cloud to catch the bodies as they washed downstream, from which they were transported to the Grand Châtelet.) But it was not until around the turn of the 18th century that the public was invited in and asked to try and identify the dead at la morgue.

Morgues Go Public

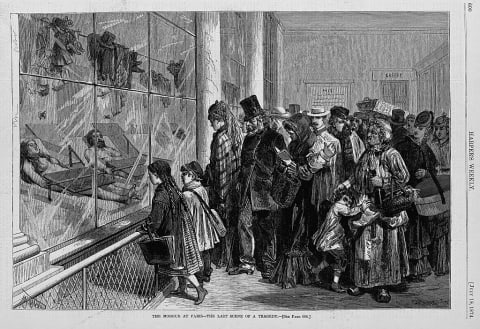

The stench emanating from the corpses at the morgue must have been unbearable, and the public exposure to the “bad humors” was one of the reasons for the creation of a new, more hygienic morgue, at the Place du Marché-Neuf on the Ile-de-la-Cité in 1804. This new morgue building (by now officially known as La Morgue) was housed in a building styled like a Greek temple that was close to the river, enabling bodies to be transported there by boat. The corpses were now displayed in a purpose-built exhibit room, with plate-glass windows and plenty of natural light, allowing crowds to gather and gawk at the corpses laid out on marble slabs. Refrigeration did not come until the 1880s, so the bodies were kept cool with a constant drip of cold water, lending the cadavers a bloated appearance. The clothes of the deceased were hung from pegs next to the dead as a further aide to their identification.

The central location of the morgue ensured a healthy traffic of people of all classes, becoming a place to see and be seen, and to catch up on the latest gossip. Its popularity as a place of spectacle grew as the 19th century progressed, stoked by being included as a must-see location in most guidebooks to Paris. On the days after a big crime had been committed, as many as 40,000 people flocked through its doors.

The morgue was also written about by luminaries such as Charles Dickens, who touched on it a number of times in his journalism, confessing in The Uncommercial Traveller (a series of sketches written between 1860 and 1869) that it held a gruesome draw:

“Whenever I am at Paris, I am dragged by invisible force into the Morgue. I never want to go there, but am always pulled there. One Christmas Day, when I would rather have been anywhere else, I was attracted in, to see an old gray man lying all alone on his cold bed, with a tap of water turned on over his grey hair, and running, drip, drip, drip, down his wretched face until it got to the corner of his mouth, where it took a turn, and made him look sly.”

Dickens also described the crowds of people flocking to the morgue to gawk at the latest arrivals, idly swapping speculation on causes of death and potential identities. “It was strange to see so much heat and uproar seething about one poor spare white-haired old man, so quiet for evermore,” he wrote.

The Evolution of the Morgue

In 1864, the morgue at the Marché-Neuf was demolished to make way for Baron Haussmann’s sweeping remodeling of Paris. The new morgue building was situated just behind Notre-Dame, again in a busy public space, reaffirming its purpose as a place to view and identify dead bodies. However, it was also in this new building that the morgue moved away from pure spectacle and began to be linked with the medical identification of bodies, as well as advances in forensics and the professionalization of policing.

The new morgue had an autopsy room, a small laboratory for chemical analysis, and rooms where police and administrators could inspect the bodies and record any murders. The emphasis shifted—the morgue was no longer purely dependent on the public to identify the bodies; it now had medical, administrative, and investigative officers doing that work, moving it closer to our modern idea of what a morgue is.

By the 1880s the fame of the Paris morgue, and admiration of its now-efficient administrative structures, had spread across the world. The word morgue began to be used to describe places where the dead were kept in both Britain and America, replacing the older term dead house and becoming synonymous with mortuary. Over time, morgue was also adopted in American English, perhaps slightly tongue-in-cheek, for rooms where newspaper or magazine archives are kept—for example, The New York Times morgue, a storehouse for historical clippings, photographs, and other reference materials related to the paper.

The Paris morgue closed its doors to the public in 1907. A combination of factors led to the decision: gradually changing public attitudes to the viewing of dead bodies, concerns over hygiene and the spread of disease, and the increasing professionalization of the police and coroners. Today, the city office that has replaced it is known as the Institut Médico-Légal de Paris. Meanwhile, the word morgue itself has come a long way from its roots in a grim spectacle. It’s now a place of professionalism and respect.

A version of this story was published in 2018; it has been updated for 2024.

Read More Articles About Death:

manual