The list of Frederick Douglass’s accomplishments is astonishing—respected orator, famous writer, abolitionist, civil rights leader, presidential appointee—and even more so when you consider that he was formerly enslaved and had no formal education. Here are 13 incredible facts about the life of Frederick Douglass.

1. Frederick Douglass bartered bread for knowledge.

Because Douglass was enslaved, he wasn’t allowed to learn to read or write. The wife of a Baltimore enslaver did teach him the alphabet when he was around 12, but she stopped after her husband interfered. Young Douglass took matters into his own hands, cleverly fitting in a reading lesson whenever he was on the street running errands for his enslaver. As he detailed in his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, he’d carry a book with him while out and about and trade small pieces of bread to the white kids in his neighborhood, asking them to help him learn to read the book in exchange.

2. Douglass credited a schoolbook with shaping his views on human rights.

During his youth, Douglass obtained a copy of The Columbian Orator, a collection of essays, dialogues, and speeches on a range of subjects, including slavery. Published in 1797, the Orator was required reading for most schoolchildren in the 1800s and featured 84 selections from authors like Cicero and Milton. Abraham Lincoln was also influenced by the collection when he was first starting in politics.

3. Douglass taught other enslaved people to read.

While he was hired out to a farmer named William Freeland, a teenaged Douglass taught other enslaved people to read the New Testament—but a mob of locals soon broke up the classes. Undeterred, Douglas began the classes again, sometimes instructing as many as 40 people.

4. His first wife helped him escape from slavery.

Anna Murray was an abolitionist and laundry worker in Baltimore and met Douglass at some point in the mid-1830s. Together they hatched a plan, and one night in 1838, Douglass took a northbound train clothed in a sailor’s uniform procured by Anna, with money from her savings in his pocket alongside papers from a sailor friend. About 24 hours later, he arrived in Manhattan a free man. Anna soon joined him, and they married on September 15, 1838.

5. Douglass called out his former enslaver.

In an 1848 open letter in the newspaper he owned and published, The North Star, Douglass wrote passionately about the evils of slavery to his former enslaver, Thomas Auld, saying, “I am your fellow man, but not your slave.” He also inquired after his family members who were still enslaved a decade after his escape.

6. Frederick Douglass took his name from a poem.

He was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, but after escaping slavery, Douglass used assumed names to avoid detection. Arriving in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Douglass, then using the surname Johnson, felt there were too many other Johnsons in the area to distinguish himself. He asked his host (named, ironically, Nathan Johnson) to suggest a new name, and Mr. Johnson came up with Douglas, a character in Sir Walter Scott’s poem The Lady of the Lake.

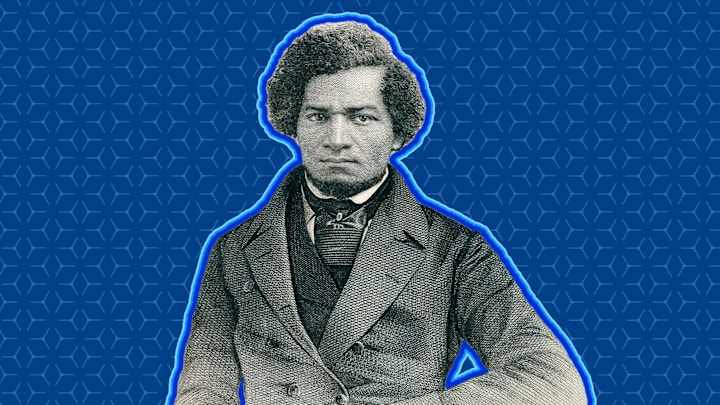

7. Douglass was deemed the 19th century’s most photographed American.

There are 160 separate portraits of Douglass, more than Abraham Lincoln or Walt Whitman, two other celebrities in the 19th century. Douglass wrote extensively on the subject during the Civil War, calling photography a “democratic art” that could finally represent Black people as humans rather than “things.” He gave his portraits away at talks and lectures based on the idea that his image could change the common misperceptions of Black men.

8. Douglass refused to celebrate Independence Day.

Douglass was well known as a powerful orator, and his July 5, 1852 speech to a group of hundreds of abolitionists in Rochester, New York, is considered a masterwork. Entitled “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July,” the speech ridiculed the audience for inviting a formerly enslaved person to speak at a celebration of the country that enslaved him. “This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine,” he famously said to those in attendance. “Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?” Douglass refused to celebrate the holiday until all enslaved people were emancipated and laws like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required citizens (including those in free states) to return escaped enslaved people to their enslavers, were negated.

9. He recruited Black soldiers for the Civil War.

Douglass was a famous abolitionist by the time the war began in 1861. He actively petitioned President Lincoln to allow Black troops in the Union army, writing in his newspaper, “Let the slaves and free colored people be called into service, and formed into a liberating army, to march into the South and raise the banner of Emancipation among the slaves.” After Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglass worked tirelessly to enlist Black soldiers, and two of his sons joined the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, famous for its contributions in the brutal battle of Fort Wagner.

10. Douglass served under five presidents.

Later in life, Douglass became more of a statesman, serving in appointed federal positions, including U.S. marshal for D.C., recorder of deeds for D.C., and minister resident and consul general to Haiti. Rutherford B. Hayes was the first to appoint Douglass to a position in 1877, and Presidents Garfield, Arthur, Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison each sought his counsel in various positions as well.

11. Douglass was nominated for vice president of the United States.

As part of the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1872, Douglass was nominated as a VP candidate, with Victoria Woodhull as the presidential candidate. (Woodhull was the first female presidential candidate, which is why Hillary Clinton was called “the first female presidential candidate from a major party” during the 2016 election.) However, the nomination was made without his consent, and Douglass never acknowledged it (and Woodhull’s candidacy itself is controversial because she wouldn’t have been old enough to be president on Inauguration Day). Also, though he was never a presidential candidate, he did receive one vote at each of two nomination conventions.

12. His second marriage caused controversy.

Two years after his wife, Anna, died of a stroke in 1882, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white abolitionist and feminist who was 20 years younger than he was. Even though she was the daughter of an abolitionist, Pitts’s family (which had ancestral ties to the Mayflower) disapproved and disowned her—showing just how taboo interracial marriage was at the time. The Black community also questioned why their most prominent spokesperson chose to marry a white woman, regardless of her politics. But despite the public’s and their families’ reaction, the Douglasses had a happy marriage and were together until his death in 1895 of a heart attack.

13. After early success, Douglass’s Narrative went out of print.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself, his autobiography, was heralded a success when it came out in 1845, with some estimating that 5000 copies sold in the first few months; the book was also popular in Ireland and Great Britain. But following the Civil War, as the country moved toward Reconstruction and narratives by formerly enslaved people fell out of favor, the book went out of print. The first modern publication appeared in 1960—during another important era for the fight for civil rights. It is now available for free online.

A version of this article ran in 2018; it has been updated for 2023.