On April 3, 1860, in St. Joseph, Missouri, a young rider (probably) named Johnny Fry stuffed a mail pouch containing 49 letters, five telegrams, and other various papers into a tailor-made saddle pack and dashed off on his horse, Sylph, heading west. Almost 2000 miles away, his California counterpart, Harry Roff, took off on his horse from Sacramento, heading east. Their rides marked the launch of the famous Pony Express, the remarkable mail system that carried correspondence and news across the western United States at breakneck speed in the days before the transcontinental telegraph and the transcontinental railroad. There are plenty of myths surrounding the historic mail delivery service, and much of what we're taught about the Pony Express in school isn't quite right. Here are 11 things you might not have known about the amazing delivery service.

1. The Pony Express covered a lot of ground, fast.

With riders traveling at an average pace of 10 miles per hour around the clock, the 1966-mile route passed through eight modern-day states in 10 days. (When the Pony Express began, only Missouri and California were officially states.) From Missouri, the route snaked through Kansas to Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada and then on to California, where it ended in Sacramento (the mail would then usually travel by boat to San Francisco). The riders carried mail from the Midwest to the West Coast in less than half the time a stagecoach could (24 days), and in a pinch, could go even faster. In 1861, riders traversed the westward route in seven days, 17 hours to get a copy of Abraham Lincoln's inaugural address to California. The Pony Express was by far the most effective way to communicate cross-country at the time—at least until the telegraph came along.

2. The Pony Express didn't operate for that long.

The Pony Express plays a bit of an oversized role in the popular imagination, considering how long it actually existed. Launched in April 1860, it operated for less than 19 months before the first trans-continental telegraph line was completed, connecting California to East Coast cities, no ponies necessary. The system officially shuttered on October 26, 1861, and the last remaining mail was delivered soon after.

3. The Pony Express required a lot of horses.

Pony Express riders typically rode for 75 to 100 miles at a stretch, but they changed horses many times over the course of their journey to ensure that their steeds could go as fast as possible. The stations were about 10 miles apart, and at every station, they changed mounts, swapping out their steeds up to 10 times a ride; the whole enterprise involved about 400 horses.

However, those steeds may not have been ponies in the proper sense—by definition, ponies are small breeds of horse under 14.2 hands (4.8 feet) tall. Accounts of the types of horses used by the Pony Express vary; in his 1893 autobiography, Pony Express co-founder Alexander Majors wrote that "The horses were mostly half-breed California mustangs, as alert and energetic as their riders, and their part in the service sure-footed and fleet was invaluable." The eastern part of the route may have also used breeds like Morgans and Thoroughbreds (now best known for their use in horse racing).

4. The Pony Express's founding was as rushed as its riders.

Alexander Majors, alongside co-founders William Russell and William Waddell, had just two months to get the Pony Express up and running—a more complicated task than it might sound. They not only had to buy hundreds of horses, but build enough stations that riders could change horses every 10 miles or so—meaning more than 150 stations across the West. The stations were usually located in remote areas decided by route efficiency rather than construction or supply convenience. Majors had to find riders and substitutes (paid around $125 a month, according to his autobiography, or around $3500 today) as well as 200 station masters who could work in those remote locations, plus buy and deliver the supplies necessary to run the stations.

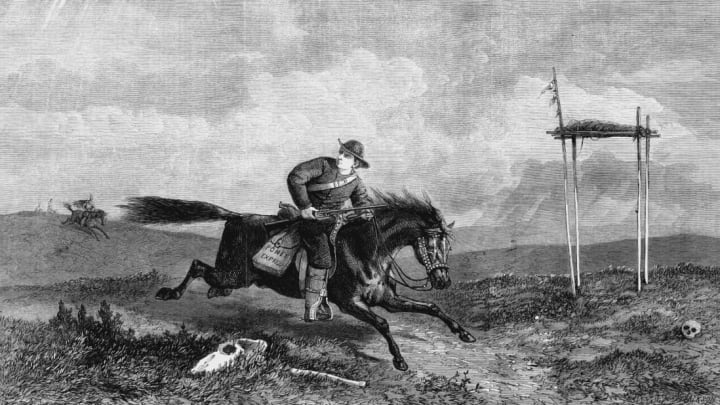

5. Pony Express riders looked a little different than you might imagine.

Contrary to myth, Pony Express riders weren't speeding across the landscape in cowboy hats wearing fringe-covered buckskins and toting guns. They were trying to minimize the weight their horse had to carry in every way, including in their dress. In Roughing It, Mark Twain (who, we should note, was not always known for his adherence to the truth) described seeing a rider for the Pony Express speed by wearing clothes that were "thin, and fitted close; he wore a 'round-about,' and a skull-cap, and tucked his pantaloons into his boot-tops like a race-rider."

Twain goes on to say that the rider was unarmed. "He carried nothing that was not absolutely necessary, for even the postage on his literary freight was worth five dollars a letter," he wrote.

6. Buffalo Bill probably wasn't involved in the Pony Express.

Very few company records exist for the Pony Express, making it hard to confirm who was really involved. Much of what we know about the entire endeavor is myth, exaggerated and reworked in tales told long after the route was shut down. Even first-person accounts tend to be full of inaccuracies—in one first-person recollection, for instance, a man who says he was born in 1864 claims he rode for the Pony Express for three years, ending in 1881, 20 years after the last mail was delivered [PDF]. And the service's most famous rider, Buffalo Bill Cody, may not have even been a rider at all. Historians disagree on whether or not there's enough reliable evidence to prove whether or not he worked for the operation, which only employed about 80 men (plus substitutes), according to the National Park Service.

"He simply liked to insert himself into history," as Buffalo Bill researcher Sandra Sagala wrote on the Smithsonian National Postal Museum's website in 2011, and there's evidence [PDF] that he was elsewhere during the times he claimed to be riding for the Pony Express.

But the Pony Express performances during his Wild West Show did significantly shape how history remembers the service. In his 1979 biography of the showman, Don Russell argues that he was, in fact, probably a rider, but that Cody undoubtedly made the Pony Express into a legend whether he was there or not. "It is highly unlikely that the Pony Express would be so well remembered had not Buffalo Bill so glamorized it," Russell wrote.

7. Pony Express riders were asked to carry bibles.

Pony Express riders were expected to be stand-up citizens, despite their later reputation as rough-and-tumble frontiersmen. Pony Express co-founder Alexander Majors asked each of his employees to take an oath saying that they wouldn't curse, drink, or fight. Riders were required to sign the oath on the inside of the specially made Bibles Majors gave each of them. Contrary to his wishes, his riders likely ignored him. First of all, the leather-bound Bibles he wanted them to carry would have weighed riders down, when the whole point was to travel as lightly as possible to maximize speed. And they probably didn't take the whole "no cursing" rule very seriously either. In 1862, Sir Richard Burton remembered stagecoach drivers hired by Majors and subject to the same oath in his book The City of the Saints: "I scarcely ever saw a sober driver; as for the profanity … they are not to be deterred from evil talking even by the dread presence of a 'lady.'"

8. The Pony Express involved special equipment.

Pony Express riders didn't just throw a standard mail bag over the back of their saddle. They had mochilas designed specially for the Pony Express—ones that look nothing like some of the products now sold as "Pony Express saddlebags." Designed to be easy to transfer from horse to horse during the minutes-long station stops, these leather covers fit over the saddle so that the rider was sitting on top of the leather, with mail pouches on either side of their legs. Twain wrote that each of these locked pouches would "hold about the bulk of a child's primer," but they could still fit a surprising amount of mail for their size, because to keep loads light (Major recalls a maximum of 10 pounds, while a former rider recalled 20), the mail was printed on thin tissue paper.

9. The Pony Express was dangerous.

There's no doubt that the route definitely ran through territory beset by conflicts between white settlers and Native Americans, but that may not have been the biggest danger. According to Christopher Corbett, author of the 2003 book Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express, the real danger along the route was the cold, not violence. In 2010, Corbett told NPR that in the few first-person accounts available in the historical record, original riders remembered the dangers of freezing during winter rides, especially if you strayed off the trail.

The Paiute War between Native Americans and white settlers in modern-day Nevada and Utah did affect service during the spring and summer of 1860 though. During one ride during the spring of 1860, express riders were escorted through Nevada to protect them from attacks. As a result, the mail took 31 days to reach Missouri, the longest of any of the eastbound Pony Express rides [PDF]. The National Park Service reports that four riders were killed on their way to deliver mail (some say that most of the employees killed by those ambushes were station masters, not riders, but at least one rider was killed during this period of conflict). The National Park Service reports that one other rider died in an accident and two froze to death, while other accounts add that at least a few riders died after being thrown from their horses. And one rider disappeared along his route never to be seen again. His mail pouch was found two years later.

10. The Pony Express led to financial ruin for its founders.

The Pony Express was founded by William H. Russell, Alexander Majors, and William B. Waddell, who ran a transportation company taking freight, mail, and passengers by stagecoach across the American West before they launched the Pony Express. Their Central Overland California & Pike's Peak Express Company, parent company to the Pony Express, would take such hard losses from operating the extra-fast route that it would be nicknamed "Clean Out of Cash and Poor Pay."

Initially, the going rate for Pony Express transport was $5 (a little over $130 in today's money) for every half ounce of mail. While that sounds a little steep compared to today's stamp, the company still lost $30—a whopping $830 today—for every letter transported, according to the Postal Museum. Knowing the service wouldn't be financially stable without it, the founders hoped to secure a government contract for their mail route, but just a few months after the launch, Congress passed a bill to subsidize the construction of a transcontinental telegraph line.

The government did fund the Pony Express during its later months—just not through Russell, Majors, and Waddell. Instead, Congress effectively made the three founders (one of whom, Russell, had recently been indicted for fraud) hand over the western part of the route to the Overland Mail Company, a subsidiary of Wells Fargo [PDF] that already ran a different stagecoach route.

11. You can still use the Pony Express to send a letter.

Each June, the National Pony Express Association stages a commemorative ride for its members over the same path that the Pony Express traveled, with volunteer riders traveling 24/7 to get mail from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California (or vice versa—they switch the route based on if it's an even or odd year) in 10 days. More than 750 riders take part, carrying up to 1000 letters in total. Anyone who's interested can pay $5 for a pre-printed commemorative letter or send their own personal letter for $10.

If you aren't the pony-riding type, you can travel the trail in other ways, like running the 100-mile endurance race held along parts of the trail in Utah each year.