One day toward the beginning of March, an unusual object arrived at a New York City airport. Carefully encased in a foam-padded, specially built wooden chair and strapped in with a bright-blue sash, it was the stuffed skeleton of one of Britain's most famous philosophers—transported not for burial, but for exhibition.

"We all refer to him as he, but the curator has corrected me. I need to keep referring to it," says University College London conservator Emilia Kingham, who prepared the item for its transatlantic voyage.

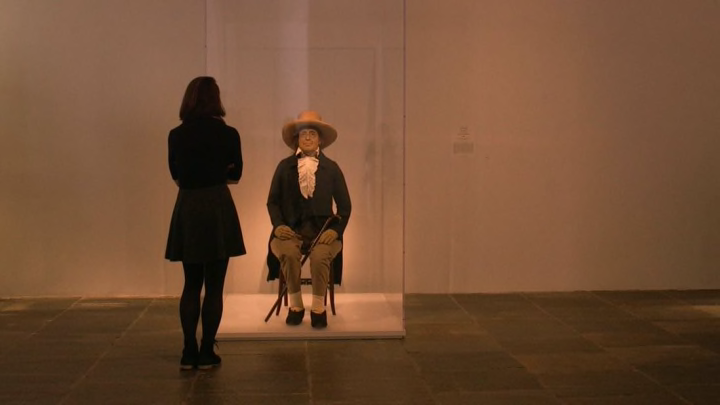

The stuffed skeleton belongs to the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who died in 1832. But for well over a century, his "auto-icon"—an assemblage including his articulated skeleton surrounded by padding and topped with a wax head—has been on display in the south cloisters of University College London. Starting March 21, it will be featured in The Met Breuer exhibition "Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now)," marking its first appearance in America.

While the auto-icon has sometimes been seen as an absurd vanity project or memento mori, according to Tim Causer, it's best understood as a product of Bentham's trailblazing work. "I would tend to ask people to reckon with the auto-icon not as macabre curio or the weird final wish of a strange old man," says the senior research associate at UCL's Bentham Project, which is charged with producing a new edition of the philosopher's collected works. Instead, "[we should] accept it in the manner in which Bentham intended it, as a sort of physical manifestation of his philosophy and generosity of spirit."

EVERY MAN HIS OWN STATUE

Bentham is best known as the founder of utilitarianism, a philosophy that evaluates actions and institutions based on their consequences—particularly whether those consequences cause happiness. A man frequently ahead of his time, he believed in a world based on rational analysis, not custom or religion, and advocated for legal and penal reform, freedom of speech, animal rights, and the decriminalization of homosexuality.

His then-unconventional ideas extended to his own body. At the time Bentham died, death was largely the province of the Church of England, which Bentham thought was "irredeemably corrupt," according to Causer. Instead of paying burial fees to the Church and letting his body rot underground, Bentham wanted to put his corpse to public use.

In this he was influenced by his friend and protégé Dr. Thomas Southwood Smith, who had published an article called "Use of the dead to the living" in 1824. Smith argued that medical knowledge suffered from the limited number of bodies then available for dissection—the Crown supplied only a handful of hanged criminals each year—and that the pool of available corpses had to be expanded to allow surgeons more practice material, lest they begin "practicing" on the living.

From his earliest will, Bentham left his body to science. (Some scholars think he may have been the first person to do so.) But he also went one step further. His last essay, written shortly before his death, was entitled "Auto-icon; or, farther uses of the dead to the living." In it, Bentham lambasts "our dead relations" as a source of both disease and debt. He had a better idea: Just as "instruction has been given to make 'every man his own broker,' or 'every man his own lawyer': so now may every man be his own statue."

Bentham envisioned a future in which weatherproofed auto-icons would be interspersed with trees on ancestral estates, employed as "actors" in historical theatre and debates, or simply kept as decoration. The point, he felt, was to treat the body in terms of its utility, rather than being bound by superstition or fear.

"It was a very courageous thing to do in the 1830s, to ask yourself to be dissected and reassembled," Causer says. "The auto-icon is his final attack on organized religion, specifically the Church of England. Because Bentham thought the church had a pernicious influence on society."

There was only one man Bentham trusted with carrying out his last wishes: Smith. After a public dissection attended by eminent scientific men, the devoted doctor cleaned Bentham's bones and articulated the skeleton with copper wiring, surrounding them with straw, cotton wool, fragrant herbs, and other materials. He encased the whole thing in one of Bentham's black suits, with the ruffles of a white shirt peeking out at the breast. He even propped Bentham's favorite walking stick, which the philosopher had nicknamed "Dapple," in between his legs, and sat him on one of his usual chairs—all just as Bentham had asked for.

But not everything went quite according to plan. The philosopher had asked to have his head preserved in the "style of the New Zealanders," which Smith attempted by placing the head over some sulfuric acid and under an air pump. The result was ghastly: desiccated, dark, and leathery, even as the glass eyes Bentham had picked out for it during life gleamed from the brow.

Seeing as how the results "would not do for exhibition," as Smith wrote to a friend, the doctor hired a noted French artist, Jacques Talrich, to sculpt a head out of wax based on busts and paintings made of Bentham while alive. Smith called his efforts "one of the most admirable likenesses ever seen"—a far more suitable topper for the auto-icon than the real, shriveled head, which was reportedly stuffed into the chest cavity and not rediscovered until World War II.

Smith kept the auto-icon at his consulting rooms until 1850, when he donated it to University College London, where Bentham is often seen as a spiritual forefather. It has been there ever since, inside a special mahogany case, despite rumors that students from Kings College—UCL's bitter rival—once stole the head and used it as a football.

"His head has never been stolen by another university," Kingham confirms. Causer says there is reason to believe the wax head was stolen by King's College in the 1990s, but never the real head. The football part of the story is particularly easy to dismiss, he notes: "We all have human heads, and kicking them doesn't do them much good, particularly 180-year-old human heads. If anybody kicked that, it would disintegrate on impact, I think." (Kingham also notes that the real head is not decomposing, as is sometimes claimed: "It's actually quite stable, it just doesn't look like a real-life person anymore. The skin is all shrunken.")

Another beloved myth has it that the auto-icon regularly attends UCL council meetings, where he's entered into the record as "present but not voting." Causer says that's not true either, although fiction became reality after the auto-icon graced the council meetings marking the 100th and 150th anniversary of the college's founding as a nod to the legend; it also attended the final council meeting of the school's retiring provost, Malcolm Grant.

FRAGILE: HANDLE WITH CARE

Bentham always wanted to visit America; Causer says he was "a big admirer of the American political system" as the one most likely to promote the greatest happiness for its citizens. But before he could accomplish in death what he failed to do in life, UCL had to mount a careful conservation operation.

The first step: a spring cleaning. The conservation team at UCL removed each item of clothing on the auto-icon piece by piece, holding carefully to the delicate areas, like a loose left shoulder and wrist, where they knew from previous x-rays that the wiring was imperfect. After a detailed condition report and an inspection for pest damage (thankfully absent), the team surface-cleaned everything.

"The clothes were quite grubby because the box that he's sitting in, it's actually not very airtight," Kingham says. A vacuum with a brush attachment took care of surface dirt and dust, but the inner items required a more thorough clean. "We determined that his linen shirt and also his underwear could do with the wash, so we actually washed those in water. It was quite exciting saying I've been able to wash Jeremy Bentham's undies." The wax head was cleaned with water and cotton swabs, and occasionally a little spit, which Kingham says is a common cleaning technique for painted surfaces.

5755620827001

Kingham's team rearranged the stuffing around the skeleton, plumping the fibers as you would a pillow. The stuffing around the arms, in particular, had started to sag, so Kingham used a piece of stockinette fabric to bind the area around the biceps—making them look more like arms, she says, but also reducing some of the strain against the jacket, which threatened the stitching.

But the most labor-intensive part of the preparation, according to Kingham, was devising a customized padded chair for the auto-icon's transport. Their final creation included a wooden boarded seat covered in soft foam that had been sculpted to hold the auto-icon lying on its back, knees bent at a 90-degree angle to minimize stress on the pelvis—another weak point. The auto-icon was bound to the chair with soft bandages, and the whole thing inserted into a travel case. The wax head was also set inside a foam pad within a special handling crate (the real head will stay at UCL, where it is currently on display), while Bentham's regular chair, hat, and walking stick got their own crates.

"We had originally joked that it might be just easier to buy him a seat on the plane and just wheel him in on a wheelchair," Kingham says, laughing.

Luke Syson, the co-curator of "Like Life," says it was touching to watch the stick and hat emerge from their travel boxes, even if the auto-icon's special chair did look a bit "like how you would transport a lunatic around 1910—or indeed 1830."

Reached by phone just after he had finished installing the auto-icon, Syson says he wanted to include the item as part of the show's emphasis on works of art made to persuade the viewer that life is present. "This piece really sums up so many of the themes that the rest of the show looks at, so the use of wax, for example, as a substitute for flesh, the employment of real clothes … And then, above all of course, the use of body parts." And the auto-icon isn't the only item in the show to include human remains—when we spoke to Syson, he was looking at the auto-icon, Marc Quinn's "Self" (a self-portrait in frozen blood), and a medieval reliquary head made for a fragment of Saint Juliana's skull, all of which are installed in the same corner of the museum.

Syson says he was initially worried the auto-icon might not "read" as a piece of art—worries that were dispelled as soon as he installed the wax head. "The modeling of the face is so fine," he says. "The observation and expression, the sense of changing personality … there's a lovely jowliness underneath his chin, the wrinkles around his eyes are really speaking, and the kind of quizzical eyebrows, and so on, all make him really amazingly present."

And unlike at UCL, where the auto-icon sits in a case, viewers at the Met are able to see him on three sides, including his back. "He sort of springs to attention on his chair, he's not sort of slumped, which you couldn't see in the box [at UCL]."

Those who have worked with Bentham's auto-icon say it encourages a kind of intimacy. Taking the auto-icon apart, Kingham says, "you really do feel a closeness to Jeremy Bentham, because you looked in such detail at his clothes, and his bones, and his skeleton." The wax head, she says, is particularly lifelike. "People who knew him have said that it's a very, very good realistic likeness of him," she notes, which made it both eerie and special to handle so closely.

"This is both the representation and the person," Syson says. "We've been calling him 'Jeremy' these last few months, and he's sort of here, and it's not just that something's here, he's here. So that's an amazing thing."

Nearly 200 years later and across an ocean, Jeremy Bentham's auto-icon has arrived to serve another public good: delighting a whole new set of fans.