One of the most tightly-controlled borders in the world is a strip of forest in northwest Tasmania. It runs almost 125 miles and separates two areas by as little as 330 feet in some places. Those that live on one side of the border rarely, if ever, cross to the other. The border isn’t a geographical barrier or a wall, and it doesn’t separate political entities or ethnic groups. Rather, it’s an invisible line where two related species of millipedes meet, but don’t mix—and no one knows why.

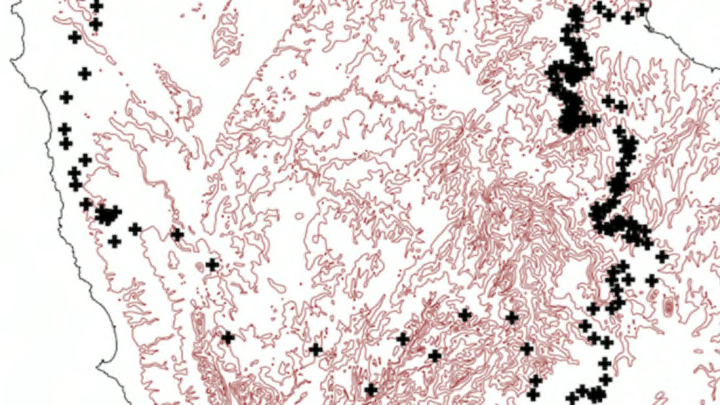

On the western side of the border lives Tasmaniosoma compitale, a 15 millimeter long, yellow-brown millipede. On the eastern side is T. hickmanorum, a similarly sized red-brown millipede in the same genus. Both species were named and scientifically described in 2010 by Bob Mesibov, a millipede specialist and research associate at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston, Tasmania. He describes them and related species as a “head + 19 rings” (the head + 17 segments with limbs + 1 segment without legs + the telson, or end segment). Mesibov spent two years mapping the species’ ranges as preparation for further field studies. When all was said and done, he had an image of a very clear division that he could not explain.

Biogeographers, the scientists that study the spatial distribution of species, have a name for these cases where species meet, but overlap very little or not at all: parapatry. It’s very common with millipedes, and occurs with other invertebrates, some plants, and some vertebrates, like birds. Normally, parapatric boundaries follow some other natural boundary like a river or the edge of a climate zone. This millipede border, though, is the longest and narrowest of any that Mesibov has seen in Australian millipedes, and doesn’t have any apparent environmental or ecological cause. It rises from sea level at Tasmania’s north coast to some 700 meters in elevation and then drops back down to sea level. It crosses many of the island’s western coastal rivers and the headstreams of two major inland river systems in the area. It runs over different geological barriers and covers different soil and vegetation types and local climates. The border seemingly ignores the vast differences in topography, geology, climate, and vegetation that it covers, and maintains its sharpness for its whole length.

Breach!

Strong as the border is, Mesibov did find places where each species had managed to cross over into the other’s territory. There’s an “island” of T. hickmanorum surrounded by T. compitale range that’s at least 15 square miles and maybe bigger—Mesibov hasn’t found its outer edge yet. There’s also a group of T. hickmanorum living several miles into T. compitale territory, where they might have been accidentally dropped by a cattle truck.

For now, Mesibov can only speculate that the border is the result of some biological arrangement between the two species, and its origin and the way it’s maintained are a mystery. It’s one that he’ll leave to other biologists to solve as he continues his regular research finding, naming, and describing millipedes new to science (he’s got 100+ under his belt, so far).

Whoever takes up the border question will have their work cut out for them. Further mapping and investigation is hindered by the fact that parts of the border cross through pastures, farms and other private property, as well as unroaded and inaccessible wilderness.