In 1950, a group of scientists proposed the International Geophysical Year (IGY), a sort of science Olympics in which nations of the world would embark on ambitious experiments and share results openly and in the spirit of friendship. The IGY, they decided, would be celebrated in 1957.

As part of the IGY, the Soviet Union vowed that it would launch an artificial satellite for space science. The U.S., not to be left behind, said that it, too, would launch a satellite. Both countries had ulterior motives, of course; the ostensibly friendly rivalry in the name of science allowed the two superpowers, already engaged in the Cold War, to quite openly develop and test long-range ballistic missiles under the guise of “friendship.”

The Soviet Union aimed to develop missiles capable of reaching both western Europe and the continental United States. Such intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) could be launched from the ground and would, Nikita Khrushchev hoped, neutralize the United States’s overwhelming nuclear superiority, which included a $1 billion squadron of B-52 bombers.

ICBMs would solve another of the Soviet Union's pressing issues: Military expenditures were gobbling up one-fifth of the economy, while agricultural output was in a severe decline. In short, there were too many bullets being produced, and not enough bread. Long-range rockets armed with nuclear weapons, already in the Soviet arsenal, could allow Khrushchev to slash the size and expense of the Red Army, forego a heavy long-range bomber fleet, and solve the food problems plaguing the country.

Meanwhile, in the United States, an Army major general named John Bruce Medaris saw a big opportunity in the International Geophysical Year: to use a missile designed for war—which the Army had been prohibited from developing further—to launch a satellite into space. But Medaris, who commanded the Army Ballistic Missile Agency in Huntsville, Alabama, would need to be creative about selling it to the Department of Defense.

- No Long-Range Rockets Allowed

- Army vs. Navy vs. the USSR

- Enter Sputnik

- Missile No. 29’s Secret Identity

No Long-Range Rockets Allowed

Medaris was working under heavy restrictions against stiff competition. In 1956, Secretary of Defense Charlie Erwin Wilson had issued an edict expressly forbidding the Army from even planning to build, let alone deploying, long-range missiles or “any other missiles with ranges beyond 200 miles.” Land-based intermediate- and long-range ballistic missiles were now to be the sole responsibility of the Air Force, while the Navy had authority for the sea-launched variety.

The idea was to avoid program redundancy and free up money to pay for the B-52 fleet, but the edict wound up having a catastrophic effect on the American missile program and its space ambitions, as author Matthew Brzezinski recounts in Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries That Ignited the Space Age.

At the time of Wilson’s injunction, the Army’s rocketry program was far ahead of the Air Force’s or Navy’s. The Army had just tested a rocket prototype called Jupiter that flew 3000 miles—but it was the new and flourishing Air Force that had the political backing of Washington. Moreover, few in the capital were worried about the Soviets developing long-range missile capability. Many believed the Soviets didn’t have a prayer at developing one before the technically advanced United States, and in the meantime, the U.S. had overwhelming nuclear bomber superiority. When you got right down to it—the DoD reasoning went—who cared whether the Army, Air Force, or Navy developed American missiles?

Major General Medaris cared. He believed that, thanks to German aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency had made too much progress on ballistic missile technology to just stop now.

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States—and the Soviets—had scrambled to gather German missile technology. The U.S. lacked the ability to develop anything as powerful as Germany's lethal V-2 rocket and desperately wanted not only as much V-2 hardware as it could find but the V-2 designer himself—Wernher von Braun.

The U.S. succeeded in recruiting the engineer, ultimately assigning him to the Army’s missile agency in 1950. There Braun and his team developed and deployed the Redstone, a short-range missile that could travel 200 miles. (That’s where Wilson’s 200-mile limitation came from.) Braun also began work on a research rocket based on the Redstone that could fly 1200 miles. It was not, technically, a missile—it wasn't designed to carry deadly ordnance. Its purpose was to test thermal nose-cone shields. It was called the Jupiter C.

The 1956 injunction on Army missile development threatened the tremendous progress the Army had made. Both Medaris, who led the Army’s missile program, and Braun, who had now spent years trying to advance the rocket technology of the United States, were infuriated.

Army vs. Navy vs. the USSR

With the IGY deadline looming, Medaris saw an opportunity to save the Army’s role in rocket design. He had the genius German engineer and all the hardware necessary to do the job.

Medaris began to wage bitter bureaucratic warfare to protect the Army’s missile program. The Air Force’s program, he pointed out to defense officials, seemed not to be going anywhere—there was simply not much rush to replace bomber pilots with long-range missiles in a pilot-led organization. Worse yet, the Naval Research Laboratory, which had been given charge of the U.S. satellite entry for the IGY, was hopelessly behind schedule and underfunded. The Navy’s Vanguard program, as it was called, would never succeed in its goal on time. (Why, then, did the Navy get the coveted assignment? In large measure because the Naval Research Laboratory was an essentially civilian organization, which just seemed more in the spirit of the International Geophysical Year.)

Through all of this, it never occurred to Medaris that he was actually in a Space Race against the Soviet Union. To his mind, he was competing against the other branches of the U.S. military. To keep his missile program alive while he waged war in Washington, he allowed Braun to continue work on ablative nose cone research using the Jupiter C research rocket, not missile—Medaris could not emphasize that point enough to the Department of Defense. If it was a research rocket, it was exempt from the ban on Army missile development.

Medaris argued to Secretary Wilson that if they just gave the Jupiter C a fourth stage—that is, basically, a rocket on top of the rocket—it could reach orbital velocity of 18,000 miles per hour and get a satellite up there.

However, “not only were Medaris’s pleas gruffly rebuffed,” Brzezinski writes, but Wilson “spitefully ordered the general to personally inspect every Jupiter C launch to make sure the uppermost stage was a dud so that Braun did not launch a satellite ‘by accident.’”

So, instead, Medaris made sure that Jupiter C “nose-cone research” plunged ahead. It simulated everything about a long-range, satellite-capable ballistic missile, but it was definitely not a missile. The Jupiter C kept the Army in the rocket development business. Just in case something went south with the Navy’s Vanguard program, however, Medaris had two Jupiter C rockets put into storage. Just in case.

Enter Sputnik

Two events would happen in 1957, the International Geophysical Year, that changed the trajectory of history. First, Secretary Wilson retired. His replacement, Neil McElroy, visited Huntsville to tour the Army Ballistic Missile Agency on October 4, 1957. Second, on the same day, the Soviet Union stunned the world by launching Sputnik-1 into orbit and ushering humankind into the space age.

Braun was apoplectic. “For God's sake,” he implored McElroy, “cut us loose and let us do something! We have the hardware on the shelf.” He asked the incoming secretary for just 60 days to get a rocket ready.

McElroy couldn't make any decisions until he was confirmed by the Senate, but that didn't faze Medaris, who was so certain that his group would get the go-ahead to launch a satellite that he ordered Braun to get started on launch preparations.

What Medaris didn't anticipate was the Eisenhower White House’s response to Sputnik. Rather than appear reactionary or spooked by the Soviets’ sudden access to the skies over the U.S., the president assured the American people that there was a plan already in place, and everything was fine. The Navy’s Vanguard program would soon launch a satellite as scheduled.

One month later, there was indeed another launch—by the Soviet Union. This time the satellite was a dog named Laika. In response, both Medaris and Braun threatened to quit. To pacify them, the Defense Department promised that they could indeed launch a satellite in January, after the Vanguard’s launch. Braun, satisfied that he would get his shot, had a prediction to make: “Vanguard will never make it.”

And he was right. On December 6, 1957, the nation watched from television as the Vanguard launch vehicle began countdown from Cape Canaveral. At liftoff, the rocket rose a few feet—then blew up.

Missile No. 29’s Secret Identity

After the Navy’s failure, the Army was back in business. Medaris had his approval. The Jupiter C rocket would be allowed to carry a satellite called Explorer-1 to space.

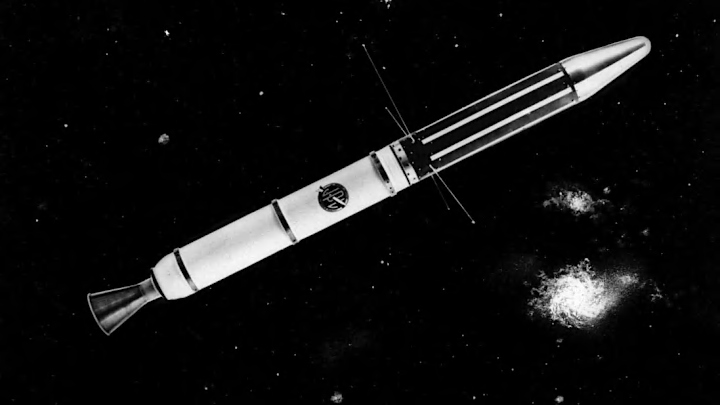

Unlike the public outreach that accompanied the Vanguard launch, however, Medaris’s rocket readying was done in total secrecy. The upper stages of the rocket were kept under canvas shrouds. The rocket was not to be acknowledged by Cape Canaveral personnel as the rocket, but rather, only as a workaday Redstone rocket. In official communications, it was simply called Missile Number 29.

The Jupiter C destined to carry the spacecraft was one of the rockets placed in storage “just in case” after the Army was locked out of the long-range missile business. On the launch pad, however, it would be called Juno. Explorer-1 was built by Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology. JPL had worked with the Army “just in case” the Navy’s Vanguard program failed. (“We bootlegged the whole job,” said William Pickering, then director of JPL.) The onboard scientific instrument, a Geiger counter developed by James Van Allen of the University of Iowa, had also been designed with the Army's rocket in mind … just in case.

Medaris wanted no publicity for his launch. No VIPs, no press, no distractions. Even the launch day was to be kept secret until the Explorer-1 team could confirm that the satellite had achieved orbit successfully.

Explorer-1 left Earth from launch pad 26 at the cape. The response is best captured by the breathless headline atop the front page of The New York Times [PDF] the following morning: “ARMY LAUNCHES U.S. SATELLITE INTO ORBIT; PRESIDENT PROMISES WORLD WILL GET DATA; 30-POUND DEVICE IS HURLED UP 2,000 MILES.”

America's first satellite would go on to circle the Earth 58,000 times over the span of 12 years. The modest science payload was the first ever to go into space, and the discovery of the Van Allen belts—caused by the capture of the solar wind’s charged particles by Earth's magnetic field—established the scientific field of magnetospheric research.

Six months after the spacecraft launched, the U.S. established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, a.k.a. NASA. (For the next three years, however, the Soviet Union dominated the Space Race, establishing a long run of firsts, including placing the first human in space.) Wernher von Braun became director of Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville and was chief architect of the Saturn V rocket that powered the moon missions. Jet Propulsion Laboratory has since launched more than 100 spacecraft across the solar system and beyond.

The unsung hero today is Major General Bruce Medaris, whose tenacity righted the U.S. rocket program. It is impossible to know how the Space Race might have ended without his contributions. We do know how his career ended, though. When he retired from the military, he rejected overtures to advise John F. Kennedy on space policy. Instead, he took a job as president of the Lionel Corporation, famed for its toy trains. He eventually set his sights on the heavens, literally, and entered the priesthood. He died in 1990 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, his legacy forever set among the stars.

Discover More Tales from the Cold War:

A version of this story was published in 2018; it has been updated for 2025.