If you spot a squirrel, Jamie Allen wants to know about it. In 2011, Allen, an Atlanta-based writer, found himself wondering exactly how many squirrels there were in the world around him. And so he and another squirrel-curious friend decided to launch the Squirrel Census, an effort to count all the squirrels in his neighborhood. Several woodland-rodent tallies later, the Squirrel Census has gone national.

The first squirrel count began in Atlanta’s Inman Park, where Allen lives, in the spring of 2012, followed by another in the fall of 2015. For each, the Squirrel Census team created an elaborate visual guide to the data for the public, squirrel-obsessed and not. Now, this fall, the project is branching out. Allen and his fellow squirrel counters are organizing a Central Park Squirrel Census for October 2018 with help from local universities, the New York City Parks Department, and other groups.

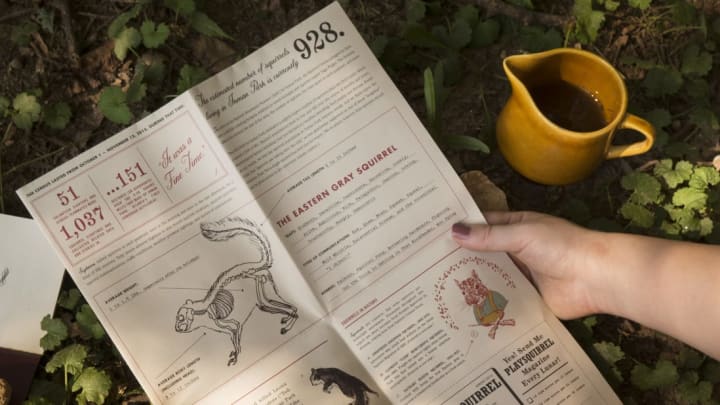

According to the Squirrel Census website, the project is focused “on the Eastern gray (Sciurus carolinensis), his pals, and his mortal enemies.” With its distinctly whimsical site design, filled with animated squirrels and an unexplained pop-up image of author Tom Clancy, you’d be forgiven for thinking the wildlife census is somewhat of a lark. And it is partly a storytelling exercise—the 2016 version of the Squirrel Census report, called Land of a Thousand Squirrels, included not just infographics and a map on the Inman Park squirrel population, but fiction and “general fun,” as Allen told Mental Floss in an email. But it has real scientific methodology, too.

The Squirrel Census team includes an Emory University epidemiologist, a veterinarian, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife fire specialist, and a wildlife illustrator, as well as a small legion of designers, fundraisers, logistics specialists, and other supporters. To estimate squirrel populations, the team uses an established wildlife-counting formula that has previously been used by scientists to study events like the Great Squirrel Migration of 1968. They break the area they want to study into quadrants and send volunteers out with clipboards, maps, and specific questions to tally squirrels over a set amount of time.

Since the first census, Allen and the Squirrel Census team have thrown events to bring their results to the public, spoken at Emory University and other colleges about their methods and results, and launched an iPhone app, called Squirrel Sighter, to allow citizen scientists to contribute data from around the world. Each time a user indicates they've seen a squirrel (dead or alive) in the app, the Atlanta-based Squirrel Census team gets an update with data on the date and time, the location of the sighting, and the weather conditions there.

The app, and the census itself, is meant as a way to “attract people to the idea of sighting squirrels, which are normally so common as to be invisible,” according to Allen, as well as to encourage people to “realize the strange joy of just taking a moment to get outside of their own heads and pay attention to something else.” And of course, in the process, they’ll gather a huge chunk of data that can be used to study wildlife populations in urban areas.

“There are many reasons to do any wildlife census,” Allen tells Mental Floss. “Information is power, it's educational, and our data has been used in academic studies on squirrel populations. But for me, the simple idea of a census allows people to appreciate their surroundings in entirely different and new ways.”