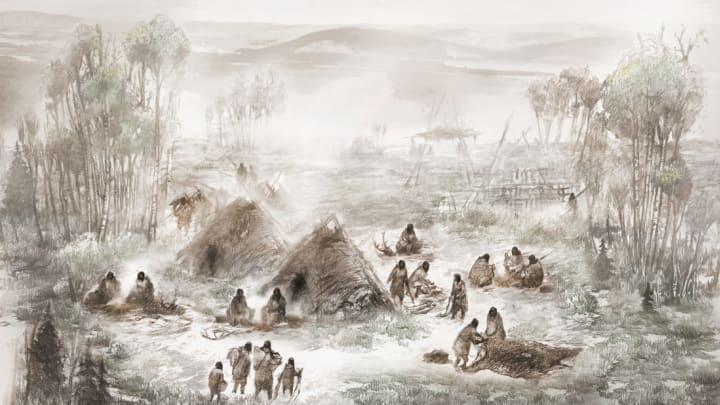

In 2013, deep in the forest of central Alaska's remote Tanana River Valley, archaeologists unearthed the remains of a 6-week-old baby at a Late Pleistocene archaeological site. The tiny bones yielded big surprises for researchers, who announced this week that the child's genome—the oldest complete genetic profile of a New World human—reveals the existence of a human lineage that was previously unknown to scientists. Related to yet genetically distinct from modern Native Americans, the infant offers fresh insights into how the Americas were first peopled, National Geographic reports.

Published in the journal Nature on January 3, the study analyzed the DNA of the infant, whom the local Indigenous community named Xach'itee'aanenh T'eede Gaay ("sunrise girl-child" in the local Athabascan language). Then, researchers used genetic analysis and demographic modeling to identify connections between different groups of ancient Americans. This allowed them to figure out where this newly identified population—named Ancient Beringians—fit on the timeline.

The study suggests that a single founding group of Native Americans separated from East Asians some 35,000 years ago. This group, in turn, ended up dividing into two distinct sub-groups 15,000 years later, consisting of both the Ancient Beringians and what would eventually become the distant ancestors of all other Native Americans. The division could have occurred either before or after humans crossed over the Bering land bridge around 15,700 years ago.

After arriving in the New World, Ancient Beringians likely remained north, while the other population spread out across the continent. Eventually, the Ancient Beringians either melded with or were replaced by the Athabascan peoples of interior Alaska.

The study provides "the first direct evidence of the initial founding Native American population, which sheds new light on how these early populations were migrating and settling throughout North America," said Ben Potter, the University of Alaska-Fairbanks archaeologist who discovered the remains, in a news release. Potter was a lead author of the study, along with Eske Willerslev and other researchers at the Center for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen's Natural History Museum of Denmark.

[h/t National Geographic]