Tucked away on a side street near Central Park, the New York Academy of Medicine Library is one of the most significant historical medical libraries in the world. Open to the public by appointment since the 19th century, its collection includes 550,000 volumes on subjects ranging from ancient brain surgery to women's medical colleges to George Washington's dentures. A few weeks ago, Mental Floss visited to check out some of their most fascinating items connected to the study of anatomy. Whether it was urine wheels or early anatomy pop-up books, we weren't disappointed.

1. FASCICULUS MEDICINAE (1509)

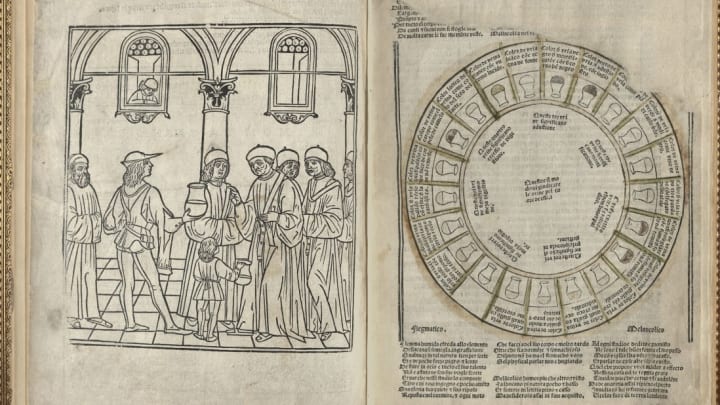

The Fasciculus Medicinae is a compilation of Greek and Arabic texts first printed in Venice in 1491. While it covers a variety of topics including anatomy and gynecology, the book begins with the discipline considered most important for diagnosing all medical issues at the time: uroscopy (the study of urine). The NYAM Library's curator, Anne Garner, showed us the book's urine wheel, which once had the various flasks of urine colored in to help aid physicians in their diagnosis. Each position of the wheel corresponded to one of the four humors, whether it was phlegmatic, choleric, sanguine, or melancholic. The image on the left, Garner explains, "shows the exciting moment where a servant boy brings his flasks to be analyzed by a professor." Other notable images in the book include one historians like to call "Zodiac Man," showing how the parts of the body were governed by the planets, and "Wound Man," who has been struck by every conceivable weapon, and is accompanied by a text showing how to treat each type of injury. Last but not least, the book includes what's believed to be the first printed image of a dissection.

2. ANDREAS VESALIUS, DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA (1543)

Andreas Vesalius, born 1514, was one of the most important anatomists who ever lived. Thanks to him, we moved past an understanding of the human body based primarily on the dissection of animals and toward training that involved the direct dissection of human corpses. The Fabrica was written by Vesalius and published when he was a 28-year-old professor at the University of Padua. Its detailed woodcuts, the most accurate anatomical illustrations up to that point, influenced the depiction of anatomy for centuries to come. "After this book, anatomy divided up into pre-Vesalian and post-Vesalian," Garner says. You can see Vesalius himself in the book's frontispiece (he's the one pointing to the corpse and looking at the viewer). "Vesalius is trying to make a point that he himself is doing the dissection, he believes that to understand the body you have to open it up and look at it," Garner explains.

3. THOMAS GEMINUS, COMPENDIOSA (1559)

There was no copyright in the 16th century, and Vesalius's works were re-used by a variety of people for centuries. The first was in Flemish printer and engraver Thomas Geminus’s Compendiosa, which borrowed from several of Vesalius's works. The first edition was published in London just two years after the Fabrica. Alongside a beautiful dedication page made for Elizabeth I and inlaid with real gemstones, the book also includes an example of a "flap anatomy" or a fugitive leaf, which was printed separately with parts that could be cut out and attached to show the various layers of the human body, all the way down to the intestines. As usual for the time, the female is depicted as pregnant, and she holds a mirror that says "know thyself" in Latin.

4. WILLIAM COWPER, THE ANATOMY OF HUMANE BODIES (1698)

After Vesalius, there was little new in anatomy texts until the Dutch anatomist Govard Bidloo published his Anatomia humani corporis in 1685. The work was expensive and not much of a financial success, so Bidloo sold excess plates to the English anatomist William Cowper, who published the plates with an English text without crediting Bidloo (a number of angry exchanges between the two men followed). The copperplate engravings were drawn by Gérard de Lairesse, who Garner notes was "incredibly talented." But while the engravings are beautiful, they're not always anatomically correct, perhaps because the relationship between de Lairesse and Bidloo was fraught (Bidloo was generally a bit difficult). The skeleton shown above is depicted holding an hourglass, by then a classic of death iconography.

5. 17TH-CENTURY IVORY MANIKINS

These exquisite figures are a bit of a mystery: It was originally thought that they were used in doctors’ offices to educate pregnant women about what was happening to their bodies, but because of their lack of detail, scholars now think they were more likely expensive collector's items displayed in cabinets of curiosity by wealthy male physicians. The arms of the manikins (the term for anatomical figures like this) lift up, allowing the viewer to take apart their removable hearts, intestines, and stomachs; the female figure also has a little baby inside her uterus. There are only about 100 of these left in the world, mostly made in Germany, and NYAM has seven.

6. BERNHARD SIEGFRIED ALBINUS, TABULAE SCELETI (1747)

One of the best-known anatomists of the 18th century, the Dutch anatomist Bernhard Siegfried Albinus went to medical school at age 12 and had a tenured position at the University of Leiden by the time he was 24. The Tabulae Sceleti was his signature work. The artist who worked on the text, Jan Wandelaar, had studied with Gérard de Lairesse, the artist who worked with Bidloo. Wandelaar and Albinus developed what Garner says was a bizarre method of suspending cadavers from the ceiling in the winter and comparing them to a (very cold and naked) living person lying on the floor in the same pose. Albinus also continued the dreamy, baroque funerary landscape of his predecessors, and his anatomy is "very, very accurate," according to Garner.

The atlas also features an appearance by Clara, a celebrity rhinoceros, who was posed with one of the skeletons. "When Albinus is asked why [he included a rhinoceros], he says, 'Oh, Clara is just another natural wonder of the world, she's this amazing creation,' but really we think Clara is there to sell more atlases because she was so popular," Garner says.

7. FERDINAND HEBRA, ATLAS DER HAUTKRANKHEITEN (1856–1876)

By the mid-19th century, dermatology had started to emerge as its own discipline, and the Vienna-based Ferdinand Hebra was a leading light in the field. He began publishing this dermatological atlas in 1856 (it appeared in 10 installments), featuring chromolithographs that showed different stages of skin diseases and other dermatological irregularities.

"While some of the images are very disturbing, they also tend to adhere to Victorian portrait conventions, with very ornate hair, and [subjects] looking off in the distance," Garner says. But one of the most famous images from the book has nothing to do with disease—it's a depiction of Georg Constantin, a well-known Albanian circus performer in his day, who was covered in 388 tattoos of animals, flowers, and other symbols. He travelled throughout Europe and North America, and was known as "Prince Constantine" during a spell with Barnum's Circus. (The image is also available from NYAM as a coloring sheet.)

8. KOICHI SHIBATA, OBSTETRICAL POCKET PHANTOM (1895)

Obstetrical phantoms, often made of cloth, wood, or leather, were used to teach medical students about childbirth. This "pocket phantom" was originally published in Germany, and Garner explains that because it was made out of paper, it was much cheaper for medical students. The accompanying text, translated in Philadelphia, tells how to arrange the phantom and describes the potential difficulties of various positions.

9. ROBERT L. DICKINSON AND ABRAM BELSKIE, BIRTH ATLAS (1940)

Robert Dickinson was a Brooklyn gynecologist, early birth control advocate, and active member of NYAM. His Birth Atlas is illustrated with incredibly lifelike terracotta models created by New Jersey sculptor Abram Belskie. The models were exhibited at the 1939 New York World's Fair, where they became incredibly popular, drawing around 700,000 people according to Garner. His depictions "are very beautiful and serene, and a totally different way of showing fetal development than anything that had come before," Garner notes.

10. RALPH H. SEGAL, THE BODYSCOPE (1948)

This midcentury cardboard anatomy guide contains male and female figures as well as rotating wheels, called volvelles, that can be turned to display details on different parts of the body as well as accompanying explanatory text. The Bodyscope is also decorated with images of notable medical men—and "wise" sayings about God's influence on the body.