During the spring of 1790, the U.S. government passed the first patent law. It got off to a slow start—only three patents were granted that year. Things eventually heated up, though, and by 1836, the total had climbed to almost 10,000. With documents piling high, the government decided to protect all the paperwork in a new, fire-resistant building. Construction began, and they placed the files in temporary storage.

Which promptly caught on fire.

The blaze gutted the building and destroyed the records—despite there being a fire station right next-door. (It was December, and a wintry freeze mucked up the pumps.) Today—and some 8 million patents later—those documents are called the “X-Patents.” Although most of them are lost, we have a barebones record of what used to be there, giving us a peek into what America’s earliest inventors were up to.

Patent X1

Samuel Hopkins of Pittsford, Vermont snagged the first patent July 31, 1790. His invention improved “the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new apparatus and Process.”

Patent X2

Joseph Sampson’s invention aided the “manufacturing of candles.” Later on, the Boston candle maker helped invent the continuous wick.

Patent X3

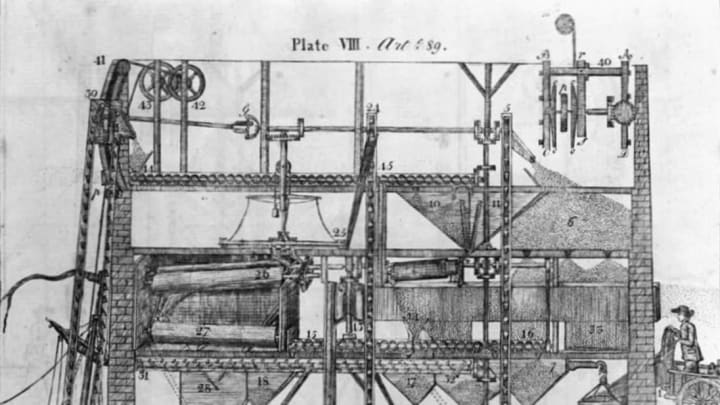

Oliver Evans of Philadelphia helped usher in the machine age, inventing an elaborate automated flour mill (top). Evans said the mill worked “without the aid of manual labor, excepting to set the different machines in motion.” (His most famous invention, though, may be the Oruktor Amphibolos, a whimsical looking dredge—and possibly the first self-powered amphibious vehicle.)

Patent X4

Francis Bailey was a Philadelphia-based printer with friends in high places, so it’s no surprise he landed a “punches for type” patent in 1791. Bailey, by the way, printed the first official copy of the Articles of Confederation.

Patent X5

Aaron Putnam’s invention improved the distilling process. Sadly, there’s no record of what he was distilling. He landed the patent just two months before the Whiskey Excise Act became law, the tax that sparked the Whiskey Rebellion.

Patent X6

John Stone of Massachusetts may have saved workers hundreds of man-hours after he invented a pile driver for bridges, which he patented March 10, 1791.

Patent X7 to X10

Philadelphia inventor Samuel Mulliken sweeps the last four spots with some versatile inventions, all patented the same day—March 11, 1791. His first invention was a “machine for threshing grain and corn.” His second invention helped break hemp, while his other two contraptions helped cut and polish marble and raise a nap on cloths.