Isaac Asimov described the solar system as the sun, Jupiter, and debris. He wasn't wrong—the sun is 99.8 percent of the mass of the solar system. But what is that giant ball of fire in the sky? How does it behave and what mysteries remain? In 2017, Mental Floss spoke to Angelos Vourlidas, an astrophysicist and the supervisor of the Solar Section at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, to learn what scientists know about the sun—and a few things they don't.

- The sun is a giant nuclear fusion reactor.

- The sun has a galactic-scale orbit.

- The sun is hot in strange ways.

- The sun has an atmosphere—and Earth is inside it.

- The iron in your blood comes from the sun’s siblings.

- The holy grail of sun science is understanding eruptions.

- A solar probe is making humanity’s first visit to a star.

The sun is a giant nuclear fusion reactor.

The sun is so incomprehensibly big that it's almost pointless to bother trying to imagine its size. Our star is about 860,000 miles across. It's so big that 1.3 million Earths could fit inside it. The sun is 4.5 billion years old, and should last for another 6.5 billion years. When it faces the final curtain, it will not go supernova, however, as it lacks the mass for such an end. Rather, the sun will grow to a red giant—destroying Earth in the process (if we last that long, which we won't)—and then contract to become a white dwarf.

The sun is 74 percent hydrogen and 25 percent helium, with a few other elements thrown in for flavor, and every second, nuclear reactions at its core fuse hundreds of millions of tons of hydrogen into hundreds of millions of tons of helium, releasing the heat and light that we love so much.

The sun has a galactic-scale orbit.

The sun rotates, though not quite the same way as a terrestrial planet like Earth. Like the gas and ice giants, the sun’s equator and poles complete their rotations at different times. It takes the sun’s equator 24 days to complete a rotation. Its poles poke along and rotate every 35 days. Meanwhile, the sun actually has its own orbit. Moving at 450,000 miles per hour, the sun is in orbit around the center of the Milky Way galaxy, making a full loop every 230 million years.

The sun is hot in strange ways.

The sun’s temperatures leave astrophysicists puzzled. At its core, it reaches a staggering 27,000,000°F. Its surface is a frosty 10,000°F, which, as NASA notes, is still hot enough to make diamonds boil. Here’s the weird part, though: Once you get into the higher parts of the sun’s corona, temperatures again rise to 3,500,000°F. Nobody knows why.

The sun has an atmosphere—and Earth is inside it.

If you saw the total solar eclipse in 2024, you saw the sun turn black, ringed by a shimmering white corona. That halo was part of the sun’s atmosphere. And it’s a lot bigger than that. In fact, Earth is inside the sun’s atmosphere. “It basically goes as far away as Jupiter,” Vourlidas told Mental Floss. The sun is a semi-chaotic system. Every 100 years or so, the sun seems to go into a small “sleep,” and for two or three decades, its activity is reduced. When it wakes, it becomes much more active and violent. Scientists aren’t sure why that is. Presently, we’re in one of those solar lulls.

The iron in your blood comes from the sun’s siblings.

The sun lacks a solid core. At 27,000,000°F, it’s all plasma down there. “That’s where most of the heavy elements like iron and uranium are created—at the cores of stars,” Vourlidas said. “When the stars explode, they are released into space. Planets form out of that debris, and that’s where we get the same iron in our blood and the carbon in our cells. They were made in some star.” Not ours, obviously, but a star that exploded in our neighborhood before our sun was born. Other elements created from the cores of stars include gold, silver, and plutonium. That is what Carl Sagan meant when he said that we are children of the stars.

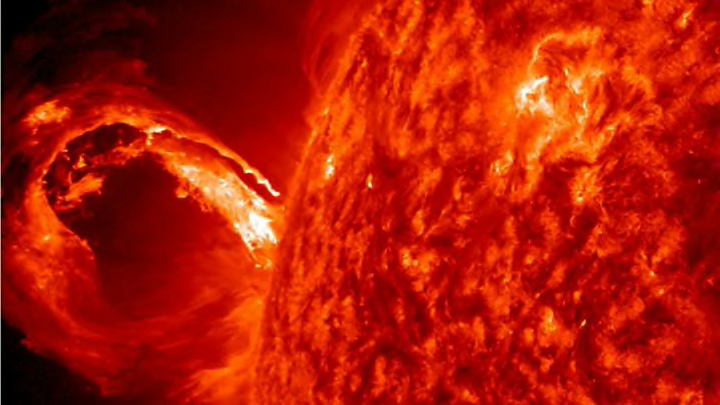

The holy grail of sun science is understanding eruptions.

The ability to predict solar storms is the holy grail for astrophysicists who study the sun. During a coronal mass ejection, a billion tons of plasma material can be blown from the sun at millions of miles per hour. The eruptions carry around 300 petawatts of energy—that's 50,000 times the amount of energy that humans use in a single year. As the structures travel from the sun, they expand, and when they hit Earth, a percentage of their energy is imparted. Those impacts can create havoc. Spacecraft are affected, airliners receive surges of X-rays, and the energy grid can be disrupted—one day perhaps catastrophically so. “Our models say it can happen every 200 years,” Vourlidas said, “but the sun doesn’t know about our models.”

The last such strike on Earth is believed to have occurred in 1859. The telegraph system collapsed, but the effect on society was minimal overall. (The widespread use of electric lighting and the first power grids were still decades away.) If Earth were to sustain a similar such destructive event today, the effects might be devastating. “It is the most violent phenomenon in our solar system,” Vourlidas explained. “We need to know when such an amount of plasma has left the sun, whether it will hit Earth, and how hard it is going to slap us.” Such foresight would allow spacecraft to power down sensitive instruments and power grids to switch off where necessary, among other things.

A solar probe is making humanity’s first visit to a star.

In 2018, NASA launched the Applied Physics Laboratory’s Parker Solar Probe to “kiss” the sun. It traveled to within 4 million miles of our star—the closest we’ve ever come—and is studying the corona and the solar wind. Before the probe’s launch, “the only way we [understood] that system [was] by seeing what the properties of the wind [were] at Earth, and then trying to extrapolate back toward the sun,” Vourlidas said. The Parker Solar Probe is measuring the sun’s wind—“how fast it is, how dense, what is the magnetic field—across multiple locations as it orbits the sun.” Once scientists get those measurements in full, theorists will attempt to devise new models of the solar wind, and ultimately help better predict solar storms and space weather events.

Read More Amazing Stories About Space:

A version of this story ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2025.