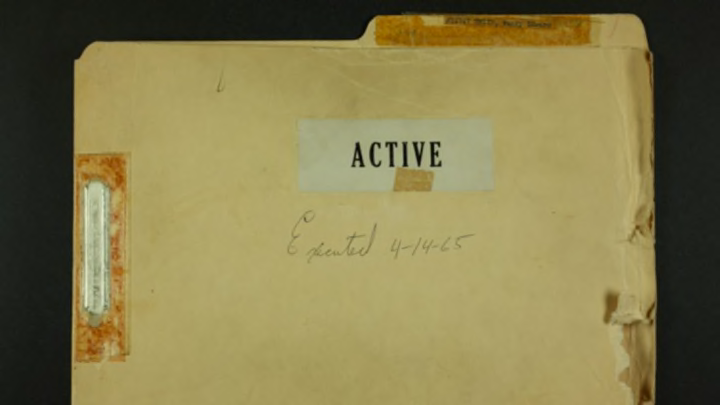

On November 15, 1959, the Clutter family—Herb and Bonnie, their daughter Nancy, and son Kenyon—were brutally murdered in their Holcomb, Kansas, home. Convicted of the crime were Perry Edward Smith and Richard Eugene Hickock, who were sent to the Kansas State Penitentiary. Soon after, the killers became the subjects of Truman Capote’s non-fiction novel, In Cold Blood. Capote conducted a number of interviews with the inmates before they were executed by hanging on April 14, 1965.

The Kansas Historical Society recently released Smith and Hickock’s inmate case files—593 pages and 727 pages, respectively—which include their criminal histories, warrants, legal correspondence, and notes to and from Capote. Here are a just few details from the files that shed light on their lives behind bars.

1. During his first stay in prison, Smith was busted for contraband.

A search of Cell 228 on March 6, 1957, when Smith was behind bars for burglary, revealed:

1 Box in the making, with drawer. Some sandpaper. 1 New 12 inch ruler. 1 Pair pliers. 1 piece of band saw blade. 1 Piece of file. 1 Jar of glue. 2 pieces of rubber innertube. 1 roulette game. 1 stinger.

Smith pleaded guilty to having the items, but told officer E. Golden that he was “of a creative nature and likes to build things … The roulette wheel was for his own amusement in order to figure out percentages.” Though it was the first report for Smith in the year that he had been in prison, the document filed by the custodial officer continued, “[he] appears to be an unstable individual who follows his own impulsive nature without weighing the consequences.” Smith was sentenced to indefinite isolation, followed by 30 days restriction.

2. During his first stint in prison, Hickock worked at the tag factory.

His duties included “taking paint off the machine and placing it on the conveyor, also is an extra operator when one is needed,” reported E.G. Peters, supervisor of the tag factory, on May 27, 1959. “This man requires little supervision. His quality of work, dependability and attitude is above average.” His work was good enough that earlier that year, Hickock had been given a raise, and made 20 cents a day.

3. Smith went on a hunger strike in the first year of his second sentence.

Kansas Memory

After going on a “self-induced starvation diet for five (5) months” that left him weighing just 108 pounds, Smith’s doctors recommended he be sent to Larned State Hospital for psychiatric evaluation. In a Special Progress Report dated October 13, 1960, that request was denied: “It would be difficult to transfer the patient that distance due to deterioration caused by self-starvation and due to maximum security measure involved in commitment to a medical institution.” (Later records in the file show that Smith was taken to a hospital.)

4. During his second sentence, Hickock took courses on the Bible.

Because he was on Death Row, Hickock couldn’t go to church—so instead, he participated in Bible Correspondence courses, according to a Special Progress Report from October 7, 1960.

5. Hickock was a college football fan.

Kansas University, specifically. In a letter to Warden Tracy Hand dated August 15, 1960, Hickock wrote, “It is that time of year when football season is just around the corner. I am quite an ardent fan of the University Kansas … The first game of the season is the 17th of September. Would it be possible for the game of the University of Kansas to be put on the speaker on top of the jail, Saturday afternoon?” Hickock’s request was granted.

6. When Capote interviewed Hickock and Smith in 1962, he also got a tour of the institution.

Kansas Memory

Capote’s requests for an interview were initially denied; though the inmates had given interviews to reporters before, the prison decided “interviews with condemned inmates serve no constructive purpose.” Eventually, though, Capote got his interview—and a tour.

The author visited and interviewed the inmates many times. In a September 1964 letter included in both Smith and Hickok's files, Capote wrote Warden Sherman Crouse informing him that he planned to visit Smith and Hickock once again. “Please do not bother to answer this request by letter,” Capote wrote, “as I will telephone you well in advance.”

Kansas Memory

Crouse forwarded the letter to Stucker, acting Director of Penal Institutions, describing Capote as “a rather well known author who is writing a book on the Clutter murder case. … Perhaps I should alert you to the fact if a man about 5 feet tall, approximately 50 years of age, and with a walk and voice such as you have seen and heard many times during your prison career, comes to your office it almost undoubtedly is Mr. Capote.”

Crouse went on to explain that Capote attended the trial and kept in touch with the two inmates since that time. “I have been informed Hickock will request that Mr. Capote attend his execution, if and when it takes place,” he wrote. “It is understood Mr. Capote is holding up the completion of his book until the fate of Hickok and Smith is finally settled.”

7. Harper Lee wanted to correspond with Smith.

Nelle Harper Lee—yes, the author of To Kill A Mockingbird—helped Capote with his research for In Cold Blood. She also visited Hickock and Smith in jail with Capote, and tried to correspond with Smith. In a March 20, 1962 letter to Colonel Guy C. Rexroad, Director of Penal Institutions, lawyer Clifford Hope wrote that Lee “was advised that Perry Smith would like to correspond with her. I trust that this privilege could not be granted unless Smith himself would make a request for it. I understand Miss Lee’s letters have been returned undelivered.”

In his reply, Rexroad made clear that “it is not possible to grant this request.” The rules of the institution mandated that inmates were only allowed to correspond and visit with members of their immediate families. “Inmates without immediate relatives, [sic] may request permission to have a friend or more distant relative approved as a correspondent. This exception cannot be applied in [Smith’s] case, since he has a father. … I am sure that the need for uniformity in the administration of the Penitentiary rules will be clear to Miss Lee and hope that she will understand the reasons that make it impossible for this office to grant her request.” (According to another document, Smith was permitted to have a 5x7 photo of Lee.)

8. Hickock told his life story to someone other than Capote.

That person was Mack Nations, who wrote an article, "From the Death House A Condemned Killer Tells How He Committed American's Worst Crime in 20,” that was published in the December 1961 issue of Male magazine. When he discovered that Hickock was also speaking to Capote, Nations was incensed—and sent letters to that effect. "Richard Eugene Hickock granted to Mack Nations exclusive rights to any and all of [his life story] forever," he wrote to Warden Hand on January 23, 1962, just a few days before Capote conducted one of his interviews. "In the event that Richard Eugene Hickock violates that contract, verbally or otherwise, with or by giving interviews concerning his life to Truman Capote or any other person, then Richard Eugene Hickock automatically forfeits forever the one-half interest the contract calls for him to receive of any and all moneys from the sale of the story by Mack Nations." Nations, who asked the warden to pass this information along to Hickock, also threatened to sue the inmate.

9. They really, really wanted radios.

Kansas Memory

Smith and Hickock repeatedly requested radios for the five men on death row at Kansas State Penitentiary. “Music is soothing to anyone’s nerves,” Hickock wrote in a 9-page letter to Robert J. Kaiser, Director of Penal Institutions, on September 12, 1963. “It keeps the mind off one’s troubles—family, financial, death, etc. A radio is the answer to our mental depression.” Smith even sent clippings of advertisements hawking radios to warden Crouse. Their requests were denied, both because of Death Row’s proximity to a segregation area, where inmates weren’t permitted to listen to radios, and because there weren’t funds to purchase radios with headphones.

10. Capote sent Smith magazines.

In a September 20, 1964 letter, Smith wrote to Capote “I finally got around to making a perusal of Bogdanovich’s article in the Sept. issue of Esquire which you sent recently. … Thank you for sending along the two outdoor mags … they are much appreciated. But please don’t send me any more … We get many of them here sometimes and it’s a waste of $$—and the outdoor, automobile and sports don’t interest me in the least anymore. … Instead of some of the magazines you have been sending, you may, if you would, send a TIME; U.S. News & World Report; or Newsweek.”

11. Smith wanted to paint a portrait of the warden.

In a bizarre letter to Crouse dated October 13, 1964, Smith asked how the warden and the Christmas spirit were "making out," and went on to say, “(smile) I thought that I would like to paint a portrait or two of you if permitted to, and finish some others too, should the art material privileges be returned :(it has been five (5) months now). … Funny thing how the Christmas spirit grabs hold of ya sometimes—but when it does, it usually puts on in a benevolent frame of mind, especially around this time of year.” (Enclosed with this letter were the aforementioned ad clippings of radios.)

Crouse passed the letter and clippings on to Nova Stucker, acting Director of Penal Institutions, and noted, “I am sending these to you ... to let you know there is still some humor left on death row; also to relay part of the attitude of a man who has been on death row for over four years and is about at the last stage of legal help. In my opinion, he would kill anyone without a thought if he saw an opportunity to make a break.”

Smith’s request for art supplies was denied.

12. They read … a lot.

Smith’s reading list included Freud Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, You and Your Handwriting, Man’s Presumtuous Brain, Life Pictorial Atlas of the World, Born Under Saturn, The Clouds, The Brain, Thimm’s Spanish, and more. Hickock, meanwhile, read Gents and Motor Trend magazines, and books like One Hundred Million Dollar Misunderstanding, Never Love a Stranger, Stiletto, Where Love Has Gone, and The Origin of Species, among others.

13. Smith sent a telegram to Capote the day before his execution.

Kansas Memory

"Am anticipating and awaiting your visit," the telegram, sent at 1:16 p.m. on April 13, 1965, read. "Please acknowledge by return wire when you expect to be here." But Capote never showed: According to an interview prison director Charles McAtee gave the Lawrence Journal-World in 2005, the author called at 2 p.m. that day to say he wouldn't be coming because "the emotional buildup to the execution would be too much to bear." (Capote's name, written in his own handwriting, was on the authorized witness list for Smith's execution, however.)

14. At least one letter sent to Smith arrived too late.

Smith corresponded with Donald E. Cullivan, whom he knew from his time in the military, for much of the time he was in prison. On April 11, 1965, Cullivan sent out another letter. “I appreciated your last letter very much,” he wrote. “I too have enjoyed your friendship and I hope I hear from you again.”

The response he got was not the one he wanted. “Dear Mr. Cullivan,” Warden Crouse wrote. “Your letter … arrived too late. The execution was carried out, as scheduled, early on the morning of April 14, 1965. Very truly yours, S.H. Crouse.”

15. They had the same last meal.

It included shrimp and strawberries.

We didn’t make it through every piece of information in these files. If you’d like to check them out yourself, head over to Kansas Memory.