By Chris Gayomali

Sitting on the nose of the constellation Taurus, about 150 light-years away from Earth in the star cluster Hyades, are the dulling embers of two white dwarf stars.

Under normal circumstances, the stars' burnt-out cores would be unremarkable. But scientists from Cambridge University peering through NASA's Hubble telescope noticed something peculiar.

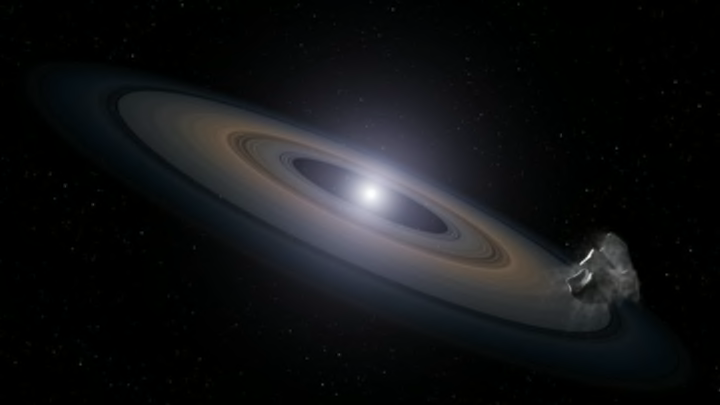

Instead of being surrounded by mostly empty space, the stars' remnants were swimming in a dusty cloud of asteroid debris, likely smashed to bits by the dwarves themselves.

Surprisingly, the matter in this instance was mostly composed of heavy elements like silicon and carbon — the chemical building blocks of planets like Earth.

[The] research suggests asteroids less than 100 miles (160 kilometers) wide probably were torn apart by the white dwarfs' strong gravitational forces. Asteroids are thought to consist of the same materials that form terrestrial planets, and seeing evidence of asteroids points to the possibility of Earth-sized planets in the same system. The pulverized material may have been pulled into a ring around the stars and eventually funneled onto the dead stars. The silicon may have come from asteroids that were shredded by the white dwarfs' gravity when they veered too close to the dead stars. [NASA]

"When these stars were born, they built planets, and there's a good chance they currently retain some of them. The material we are seeing is evidence of this," says Jay Farihi, an astronomer at Cambridge and lead author of the study. "The debris is at least as rocky as the most primitive terrestrial bodies in our solar system."

The discovery could shed light on how so-called "cosmic nurseries"—which produce stars and planets much like our humble blue marble—gather materials to create new worlds.

"If you have giant rocks that are many kilometers in size flying about, it is almost certain that planet formation has happened," Farihi told the Los Angeles Times. "It's like seeing a bunch of Lego blocks strewn around a kid's room. You know they were building something, but you don't know exactly what they are building."

It should also give astronomers a clearer indication of what happens when our own sun eventually runs out of fuel.

More from The Week...

7 Perfect Homes for Stargazing

*

Why Babies in Every Country on Earth say "Mama"

*

7 Curious Currencies from Around the World