If you look closely at a 19th century map of Africa, you’ll notice one major way that it differs from contemporary maps, one that has nothing to do with changing political or cartographical styles. More likely than not, it features a mountain range that no longer appears on modern maps, as WIRED explains. Because it never existed in the first place.

The “Mountains of Kong” appeared on almost every major commercial map of Africa in the 1800s, stretching across the western part of the continent between the Gulf of Guinea and the Niger River. This mythical east-west mountain range is now the subject of an art exhibition at London’s Michael Hoppen Gallery.

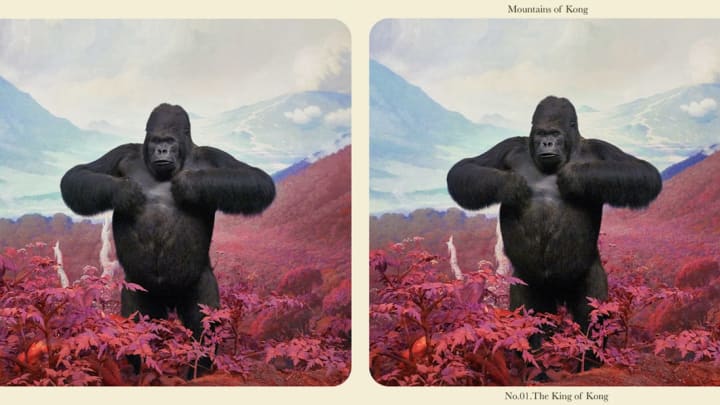

In "Mountains of Kong," stereoscopic images by artist Jim Naughten—the same format that allowed Victorians with wanderlust to feel like they’d seen the world—reveal his view of the world of wildlife that might have existed inside the imagined mountains. As the gallery describes it, “he imagines a fictitious record made for posterity and scientific purposes during an expedition of the mountain range.” We’ve reproduced the images here, but to get the full effect, you’ll have to go to the gallery in person, where you can view them in 3D with a stereoscope (like the ones you no doubt played with as a kid).

Naughten created the images by taking two photographs for each, and moving the camera over some 3 inches for the second photo to make a stereoscopic scene. The landscapes were created by shooting images of Scottish and Welsh mountains and dioramas in natural history museums, using Photoshop to change the hues of the images to make them seem more otherworldly. His blue-and-pink-hued images depict fearsome apes, toucans sparring with snakes, jagged peaks, and other scenes that seem both plausible and fantastical at the same time.

The Mountains of Kong appeared in several hundred maps up until the 20th century. The first, in 1798, was created by the prominent geographer James Rennell to accompany a book by Scottish explorer Mungo Park about his first journey to West Africa. In it, Park recounts gazing on a distant range, and “people informed me, that these mountains were situated in a large and powerful kingdom called Kong.” Rennell, in turn, took this brief observation and, based on his own theories about the course of the Niger River, drew a map showing the mountain range that he thought was the source of the river. Even explorers who later spent time in the area believed the mountains existed—with some even claiming that they crossed them.

The authority of the maps wasn’t questioned, even by those who had been to the actual territory where they were depicted as standing. Writers began to describe them as “lofty,” “barren,” and “snow-covered.” Some said they were rugged granite peaks; others described them as limestone terraces. In almost all cases, they were described as “blue.” Their elevation ranged from 2500 feet to 14,000 feet, depending on the source. Over the course of the 19th century, “there was a general southward ‘drift’ in the location,” as one pair of scholars put it.

Though geographers cast some doubt on the range’s existence as time went on, the Mountains of Kong continued to appear on maps until French explorer Louis-Gustave Binger’s Niger River expedition between 1887 and 1889, after which Binger definitively declared their nonexistence.

By 1891, the Mountains of Kong began dropping off of maps, though the name Kong still appeared as the name of the region. By the early 20th century, the mountains were gone for good, fading into the forgotten annals of cartographic history.

[h/t WIRED]

All images courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery.