MAD magazine has always prided itself on being a subversive, counter-culture presence. Since its founding in 1952, many celebrated comedians have credited the publication with forming their irreverent sense of humor, and scholars have noted that it has regularly served as a primer for young readers on how to question authority. That attitude frequently brought the magazine to the attention of the FBI, who kept a file on its numerous perceived infractions—like offering readers a "draft dodger" card or providing tips on writing an effective extortion letter.

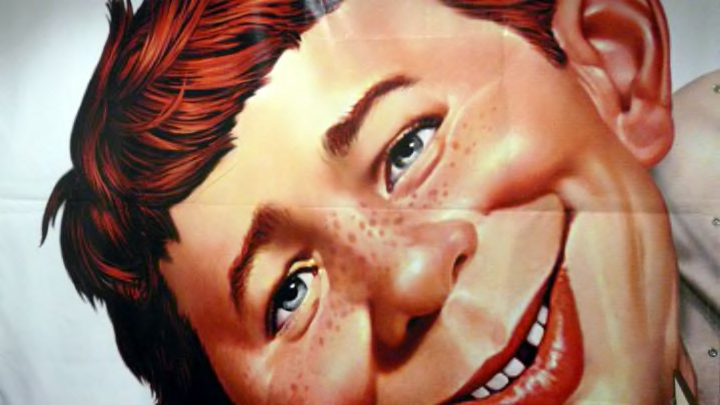

The magazine's "Usual Gang of Idiots" outdid themselves in late 1967, though, when issue #115 featured what was clearly a phony depiction of U.S. currency. In addition to being valued at $3—a denomination unrecognized by the government—it featured the dim-witted face of MAD mascot Alfred E. Neuman.

When taken at its moronic face value, there was absolutely no way anyone with any sense could have confused the bill for actual money. But what MAD hadn't accounted for was that a machine might do exactly that. Around the time of the issue's release, automated coin change machines were beginning to pop up around the country. Used in laundromats, casinos, and other places where someone needed coins rather than bills, people would feed their dollars into the unit and receive an equal amount of change in return.

At that time, these machines were not terribly sophisticated. And as a few enterprising types discovered, they didn't have the technology to really tell Alfred E. Neuman's face from George Washington's. In Las Vegas and Texas, coin unit operators were dismayed to discover that people had been feeding the phony MAD bill into the slots and getting actual money in return.

How frequently this happened isn't detailed in any source we could locate. But in 1995, MAD editor Al Feldstein, who guided the publication from its origins as a slim comic book to netting 2.7 million readers per issue, told The Comics Journal that it was enough to warrant a visit from the U.S. Treasury Department.

"We had published a three-dollar bill as some part of an article in the early days of MAD, and it was working in these new change machines which weren't as sensitive as they are now, and they only read the face," Feldstein said. "They didn't read the back. [The Treasury Department] demanded the artwork and said it was counterfeit money. So Bill [Gaines, the publisher] thought this whole thing was ridiculous, but here, take it, here's a printing of a three-dollar bill."

Feldstein later elaborated on the incident in a 2002 email interview with author Al Norris. "It lacked etched details, machined scrolls, and all of the accouterments of a genuine bill," Feldstein wrote. "But it was, however, freakishly being recognized as a one-dollar bill by the newly-introduced, relatively primitive, technically unsophisticated change machines … and giving back quarters or whatever to anyone who inserted it into one. It was probably the owner of those machines in Las Vegas that complained to the U. S. Treasury Department."

Feldstein went on to say that the government employees demanded the "printing plates" for the bill, but the magazine had already disposed of them. The entire experience, Feldstein said, was "unbelievable."

The visit didn't entirely discourage the magazine from trafficking in fake currency. In 1979, a MAD board game featured a $1,329,063 bill. A few decades later, a "twe" (three) dollar bill was circulated as a promotional item. The bills were slightly smaller than the dimensions of actual money—just in case anyone thought a depiction of Alfred E. Neuman's gap-toothed portrait was evidence of valid U.S. currency.