In the mid-1990s, the World Wide Web offered its users a new way to communicate. It also paved the way for a whole new era of social faux pas. Internet etiquette, or "netiquette" as it came to be known, dictated that decent manners still had a place in the digital sphere. While many of the early web tips published in books, articles, and memos still apply today, some are best left in the age of dial-up.

1. Keep email signatures short.

Needlessly long email signatures were even more obnoxious in 1995 than they are today. That's because in the early days of the internet, every line of text took up precious processing time that was equivalent to money out of the pocket of the person reading it. "Remember that many people pay for connectivity by the minute, and the longer your message is, the more they pay," Sally Hambridge of Intel Corporation wrote in Request for Comments (RFC): 1855, a netiquette memo published in 1995. For web users compelled to include a signature, she suggested shaving their information down to "no longer than four lines."

2. Don't expect immediate responses.

The internet made it possible to have a long-distance written correspondence with someone in practically real time. But even though emails could be sent in an instant, that didn't stop some people from taking their sweet time to respond. For a story published in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1996, one web user told reporter Ramon G. McLeod, "I had my own mother flame me for not answering her quickly enough ... People really expect an answer—and fast."

For someone used to talking on the phone or in person, the online waiting game could be infuriating. But most netiquette guides stated that a delayed response was no reason to be offended, especially if the two parties were living in different time zones.

3. Turn off the caps lock.

Like using their indoor voices in the real world, polite citizens of the web know to use mixed case in typed communication. But not everyone was quick to catch on to this practice 20 years ago. (According to The New York Times, former president Bill Clinton became an early offender when he sent an email written in all caps to the prime minister of Sweden in 1994.) In his Chronicle article on netiquette, McLeod wrote that live chatting with caps lock on was like "yelling in a restaurant."

4. Lighten the mood with emoticons.

Looking for a way to express playfulness or sarcasm to a web user halfway across the world? Netiquette guides from 1995 recommended using a novel invention called the "emoticon." In The Net: User Guidelines and Netiquette, author Arlene H. Rinaldi wrote, "Without face to face communications your joke may be viewed as criticism. When being humorous, use emoticons to express humor." But Hambridge warned readers to use the sideways smiley face with caution, fearing it might become the "no offense" of the internet age. "Don't assume that the inclusion of a smiley will make the recipient happy with what you say or wipe out an otherwise insulting comment," she wrote.

5. Tag spoilers.

On top of spam and viruses, the internet introduced a whole new type of threat to its users: spoilers. Today's bloggers know to preface spoilers with warnings (for the most part), but before this became common protocol, logging onto a film or TV message board was a risk. Netiquette experts like Chuq Von Rospach helped write spoiler tags into the internet rule book. In his online guide A Primer on How to Work With the Usenet Community, he wrote, "When you post something (like a movie review that discusses a detail of the plot) which might spoil a surprise for other people, please mark your message with a warning so that they can skip the message ... make sure the word 'spoiler' is part of the 'Subject:' line."

6. Don't ask strangers how the internet works.

Using the web in the 1990s meant possibly attracting unwanted attention from newbies begging you to lend your tech expertise. Hambridge did her best to discourage this: "In general, most people who use the internet don't have time to answer general questions about the internet and its workings." Instead of relying on strangers to teach them about the internet, she told readers to refer to one of the many books and manuals written just for that purpose. If web users neglected this important piece of netiquette, they risked getting called out on it. Hambridge wrote, "Asking a Newsgroup where answers are readily available elsewhere generates grumpy 'RTFM' (read the fine manual—although a more vulgar meaning of the word beginning with 'f' is usually implied) messages."

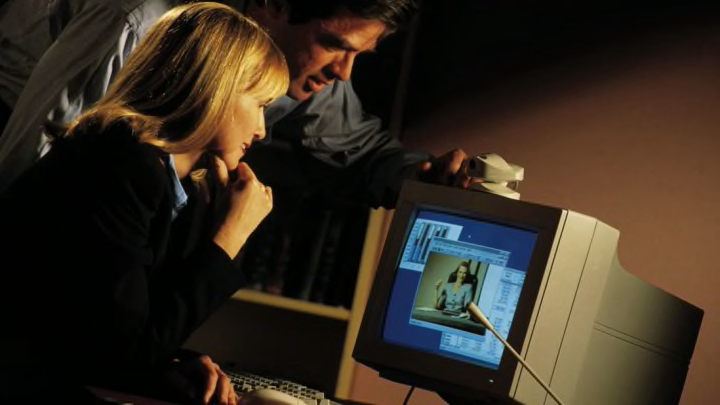

7. Keep flirting to a minimum.

Places to find dates online appeared shortly after the web went public, but that didn't stop people from flirting on unrelated message boards and email chains. Stacy Horn, founder of the web forum Echo, explained to The New York Times in 1995 how some users abused the service's high-priority "yo" tag for this purpose:

"There's a whole etiquette of when to yo, when not to yo. A man new to Echo gets on and yos all the women. That's considered impolite. A frequent thing that men do is, 'Yo, Horn, what are you wearing?' or 'Yo, Horn, do you come here often?' ... I don't know why they think stupid, banal lines are more effective on line than off."

On top of bothering the recipient, inappropriate messages could also come back to haunt the sender if they ever got out. The Chronicle shared this tip: "If you aren't sure about the security of e-mail on either end of such tender correspondence, send a Shakespearean sonnet instead of something more steamy."

8. Don't log in during rush hour.

In 1995, the World Wide Web consisted of around 16 million users—measly by today's standards but enough to clog networks during peak times. To make virtual rush hour more bearable, Hambridge suggested "spreading out the system load on popular sites" by taking a break when everyone seemed to be online at once. By waiting to log on during off hours, web users could enjoy exhilarating download speeds of 56 kilobits per second.

9. Let grammar mistakes slide.

For web browsers who shuddered at the sight of a misplaced comma or the wrong use of "your," Chuq Von Rospach had some sage advice: Get over it. He wrote in his netiquette manual:

"Every few months a plague descends on Usenet called the spelling flame. It starts out when someone posts an article correcting the spelling or grammar in some article. The immediate result seems to be for everyone on the net to turn into a sixth grade English teacher and pick apart each other's postings for a few weeks. This is not productive and tends to cause people who used to be friends to get angry with each other."

10. Avoid flamewars.

The sacred tradition of arguing with a stranger through a computer screen can be traced back to the internet's beginnings. The San Francisco Chronicle spoke with one early web user whose advice for avoiding "flames" boiled down to "don't feed the trolls":

"A couple months back, Gregori recalls, an obnoxious chatter who used the nickname 'Dummy' was barging into chat groups. He was 'just ragging on everyone, calling everyone stupid and just being generally a pain,' Gregori says. 'He was just ignored, which is the worst thing you can do to a flamer like that.'"

Feel free to apply that strategy to your modern web scuffles.